All good with consumer goods?

With FMCG stocks at historical highs, the question is: Will the valuations last?

Rajkumar / Mint via Getty Images The best buy-and sit-on-it investments in India over the last decade have been consumer stocks. Rising incomes have prompted a growing number of people to spend more on everyday products such as soaps, shampoos, hair gels and deodorants. As a result, the sales and profit growth in the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector has, over time, rivalled businesses in other sectors.

Rajkumar / Mint via Getty Images The best buy-and sit-on-it investments in India over the last decade have been consumer stocks. Rising incomes have prompted a growing number of people to spend more on everyday products such as soaps, shampoos, hair gels and deodorants. As a result, the sales and profit growth in the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector has, over time, rivalled businesses in other sectors.

As FMCG companies have grown, so have their valuations, resulting in stock price growth outpacing profit growth. India’s three largest FMCG companies—Hindustan Unilever (HUL), Godrej Consumer Products Limited (GCPL) and Dabur—trade at a price earnings (PE) multiple of between 40 and 50. HUL’s premium is far in excess of the 17 times PE its parent Unilever commands.

Is this outperformance likely to last? And should investors with a 10-year horizon stay invested? The answer is ‘yes’, as FMCG stocks will, in all likelihood, produce returns in line with the market, and with much less volatility.

Over the past 15 years, the BSE FMCG Index has compounded at 17 percent. To understand the outperformance of the sector, it’s best to trisect this period: During the first five years (till 2008), FMCG companies performed in line with the market, with multiples between 15 and 20. The market focussed on growth through leverage and infrastructure, and banking companies were the flavour of the season. As late as 2008, a quasi-consumer player Hero MotoCorp, the world’s largest two-wheeler maker, was available at a 5 percent dividend yield (it is down to 2.4 percent today).Between 2008 and 2013, FMCG companies registered massive profit growth, aided partly by the large amount ($8.5 billion a year) spent on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA). As profits surged at an average of 20 percent a year, the FMCG Index rose by 24.5 percent a year. This was also when the global slush of money—brought on by quantitative easing in the US, Europe and Japan—brought fund managers to India who were happy with a 2 percent dividend yield. A leading fund manager, who declined to be named, recounted a conversation he’d had with a Japanese fund manager: “Even if I get zero percent price appreciation, I am okay, as interest rates in Japan are negative.” Stock price multiples moved up steadily.

The period between 2013 and 2018 has been the most peculiar. Two droughts, a slowing of MNREGA spends and input price deflation have meant that FMCG companies have found it hard to grow both topline and bottomline. Sample this: HUL’s topline grew at 6 percent a year, bottomline at 3.4 percent. Sales at GCPL rose by 7 percent profits rose by 10 percent. Nestle India grew at 2.2 percent, with profits growing even slower at 1.7 percent. Still, stock prices for the three have risen at 22, 22, 10 percent respectively a year.

It is this divergence in performance over the last five years that has prompted investors to question how long valuations for FMCG companies will remain elevated. The simplest argument made is that as other sectors start performing, investors will move money there. What remains to be seen is whether FMCG stocks go through a period of flat prices even as earnings increase, or if their prices decline in the interim.

undefinedThe stock price growth has outpaced profit growth of FMCG companies[/bq]

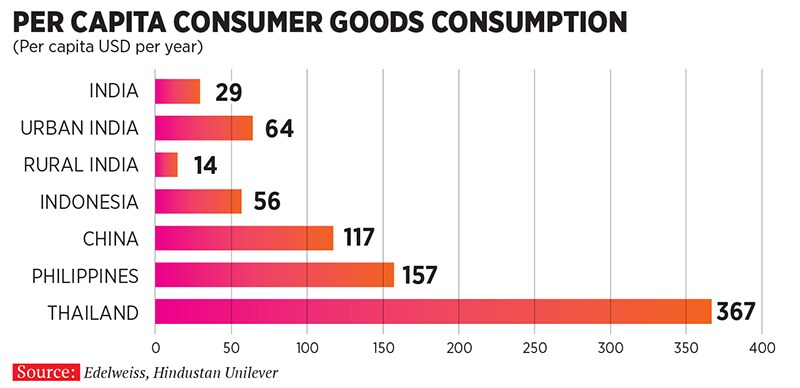

Proponents of consumer businesses argue that India’s consumer party is just getting started, and point to the hockey stick curve in spending that a country goes through when per capita GDP is between $3,000 and $8,000. India’s per capita GDP in 2017 was $1,852, and at current growth rates it is six years away from a national income of $3,000 per person a year.

“Don’t attempt to ride themes,” says Bharat Shah, executive director at ASK, who runs India’s largest portfolio management scheme. “The large size of the opportunity, the reasonably predictable strong and durable earnings growth make me believe that the valuations of quality consumer franchises will sustain.” Shah also cautions that there are threats to the moats of FMCG companies: The growing challenge from online could possibly dilute distribution advantage the growth of large retailers could cause pressures on margins. “Best to stick to companies with outstanding and hard-to-beat brands, enjoying strong consumer relevance,” he adds.

In the next two years, rural growth is likely to revive as the government plans to hike minimum support prices for crops, and there is increased social sector spending. In the latest quarter results, HUL pointed out that rural sales were growing twice as fast as urban sales, albeit from a lower base.

So far, investors who’ve aimed to time the market in the past have failed. In 2014, with the NDA being elected to power at the Centre, the most crowded trade in the market was switching from consumer stocks to industrials, infrastructure and mining companies. Nearly four years since then, FMCG stocks have beaten the benchmark Sensex by 5.2 percentage points.

Ultimately, FMCG valuations are a function of the market. “Relative to the multiples of other industries, the multiples for consumer companies have always been higher. So it stands to reason that when the index is trading at a [historically] high multiple, consumer companies would accordingly be priced upwards,” says Vivek Karve, chief financial officer at Marico.

As long as equity markets do well, your consumer stocks are in safe hands.

First Published: Mar 23, 2018, 09:54

Subscribe Now