Tata Motors' R&D Focus

With its big R&D push, Tata Motors has begun the serious work of transforming itself into a global auto company

As they say, looks can often be misleading. At first glance, the Engineering and Research Centre (ERC) inside the Tata Motors’ factory in Pimpri doesn’t seem to be the kind of place where great ideas are born. The paint on the walls is a dull shade of blue and white, the same colour as the uniform that employees sport, there are helmets strewn all over the place, the window panes in the visitors’ toilets are broken and the chairs in the long boardroom are anything but comfortable. To the untrained eye, everything about the place seems practical and mundane.

But then a casual visitor to the plant may not quite know this: The ERC is the nerve-centre of the biggest research and development effort that any Indian corporation has mounted in recent times. Today, the company has about 5,500 people working in R&D spread across India and the rest of the world. At any given point in time, there are several R&D projects going on both at the company and inside many global universities, different start-up companies, and different vendor partners that Tata has collaborated with across the US, Europe and India.

The plethora of work is astounding: From electric vehicles, fuel cells, engine development, hybrid technology to battery research or even simple things like a remote-controlled door opening device or boot lid or a smart starter motor or just a glass winding mechanism that’s more efficient. So there’s an electric car undergoing field trials on the streets in the UK. An electric version of the Ace commercial vehicle is also on trial. A parallel hybrid bus trial is now on in Mumbai, plus a fuel cell bus that was debuted as a concept at the Auto Expo in January. Work is also on to meet new Indian emission norms like BS IV and BS V.

The acquisition of Jaguar Land Rover was a game-changer in this technology game. In early 2011, Ratan Tata spoke about Tata Motors and Jaguar and Land Rover cooperating for an engine development programme in the company’s annual report. The goal is “to optimise the synergetic strengths between JLR and Tata Motors in India” he had said. These would be smaller displacement engines that could be used both by Tata Motors and JLR. Take the case of the 5-litre engine developed by Jaguar engineers, considered to be one of the best of its kind. Yet, a 5-litre engine is not exactly the future. JLR needs smaller displacement engines which comply with tighter emission norms. So does Tata Motors. For the past one year, engineers from both JLR and Tata Motors have been working on these new engines.

No other Indian car maker has gone this distance to develop research and development capabilities. Mahindra and Mahindra has made a start with its 1,200-man R&D centre in Chennai. But it focussed only on utility vehicles, whereas Tata aspires to be a full-line auto firm with global footprint. Market leader Maruti-Suzuki is looking to open its own research centre in India in two years’ time, after depending on parent Suzuki for nearly three decades.So why is Tata Motors pushing so hard? Lord Bhattacharyya, chairman of the Warwick Manufacturing Group based in Birmingham, and who is partnering Tata Motors to produce an electric car on the Indica platform for the European market, says the lens to be used when looking at Tata Motors’ R&D effort is that it is an attempt by an Indian company to build a product that can thrive in an open marketplace. “Your product has to be globally competitive, be it in technology, pricing, quality… everything. It has to compete with the best in the world. The Japanese have it, the Koreans have it and even the Chinese have been able to do it… in India, it is only fitting that Tata Motors does that. If they didn’t do R&D, they would never survive,” he says.

In the last decade, despite the success of the Tata Ace, and the global recognition it earned for its frugal engineering skills in creating the Nano, R&D remains its Achilles heel. And perhaps the only real reason—apart from quality—that could stop it from going beyond its tag as the world’s tenth largest automobile firm.

In the past, the easy way was to do it through licences—that’s how many companies in India have gone about their product development. But now, global competition is at Tata’s door step.

“In some ways Tata Motors is ahead of the rest but it is also because the company is under threat,” says a senior executive of a rival car company who did not want to be quoted. All the major auto firms—including Daimler, VW, Volvo and Toyota—have already arrived in India.

The man tasked with the responsibility of upping the ante knows a thing or two about setting new standards in technology. Dr. Tim Leverton, its chief of R&D, has a phenomenal track-record in the automotive industry. He was the chief engineer at BMW and helped build the new generation Rolls Royce Phantom. In 2006, he was also the engineering director at JCB, one of the world’s largest industrial and agricultural equipment manufacturing companies and in charge of building the Dieselmax, the fastest diesel engine in the world. So what made him pick Tata Motors? “I was attracted by the ambition of Tata Motors and their strong commitment to backing that ambition with investment and a readiness to disruptively innovate. I feel that India is one of the most exciting business environments in the world for the next era and wanted to be a part of that,” he says.

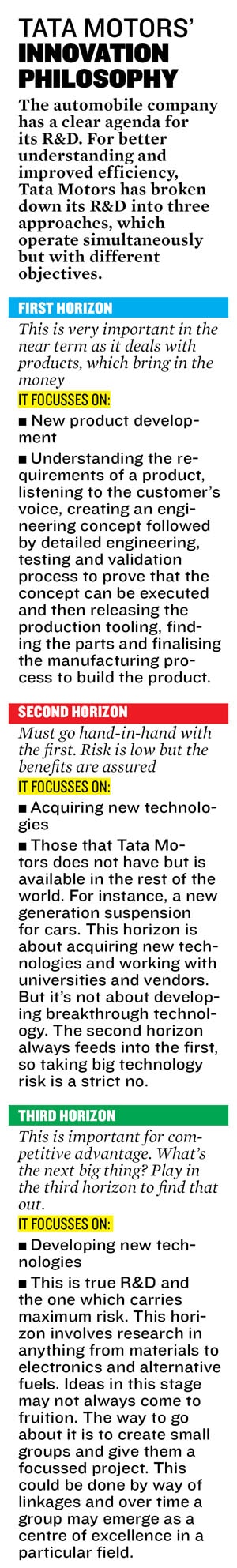

To bind all the different research projects together, Leverton has taken a leaf out of Apple’s model of innovation. Tata Motors will now act as an integrator for innovations that have come from Korea, the UK or elsewhere.

Leverton regularly shuttles between the hubs—one in Pune and the other at the European Technical Centre at Warwick. And he keeps a constant eye open for innovative ideas from the larger eco-system. It is a pretty serious attempt at collaboration. So much so that Dr. Leverton says he vets every email that he receives from anybody in the world who claims to have made a technology breakthrough. “There is a team which follows up each and every claim,” he adds. The hunt for the higher ground has begun.

First Published: Feb 28, 2012, 06:13

Subscribe Now