What was to be a 30-minute meeting with Rajesh Mehta, founder and executive chairman of Rajesh Exports Ltd, went on for 180 minutes. While the 52-year-old had much to talk about where his India-listed company is concerned—it exported almost 130 tonnes of gold last fiscal and refines nearly 35 percent of the total gold mined in the world—he was equally inundated with phone calls and impromptu meetings with company executives and clients.

Mehta’s small corner office, on the first floor of Batavia Chambers on Kumara Krupa Road in Bengaluru, near the official residence of Karnataka’s chief minister, is dimly lit. His large and heavy worktable occupies most of the space. On one side of the table top are numerous statues of Lord Ganesha, worshipped as the remover of obstacles and also considered the god of intellect and wisdom. There are more than 300 Ganesha idols, clarifies Mehta some are made from silver, gold and ivory, while others are studded with rubies and opals. “We [my family] are Jains, and we believe in Ganesha. He is an auspicious god,” says Mehta.

Six minutes into our meeting, Mehta excuses himself and picks up one of his four mobile phones. Only one of these is a smartphone (an iPhone 4 series from 2010-11), while the rest are mid-priced feature phones. His conversation is in Gujarati. Minutes later, he answers another call, on another phone, where he breaks into fluent Kannada. Mehta claims to be conversant in four other Indian languages as well.

Mehta has amassed a personal fortune of $1.88 billion after starting his company Rajesh Exports in 1989, along with his elder brother Prashant Mehta, 54, who is managing director of the company. What started off as a gold export business—in the years that India was under The Gold (Control) Act of 1968—has grown manifold to include mining, refining and retailing of the precious metal. In July 2015, Mehta bought the Valcambi gold refinery in Switzerland, one of the largest gold refineries in the world, in an-all cash deal for $400 million. Even after the big-ticket acquisition, Rajesh Exports has cash reserves and surplus of $405 million.

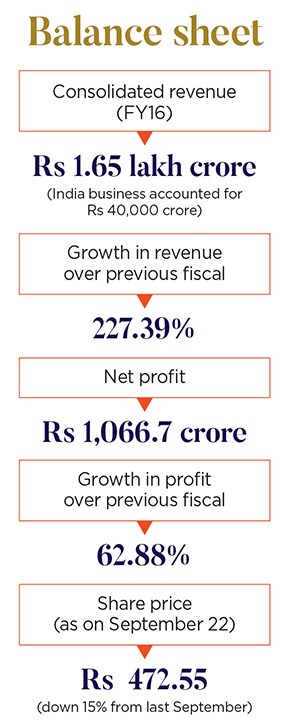

The Valcambi acquisition, while bolstering Rajesh Exports’ consolidated turnover by Rs 1 lakh crore, has also added to Mehta’s ballooning personal wealth. In the 2015 Forbes India Rich List, he ranked 65th, with a personal wealth of $1.7 billion, rising 23 places since the previous year. Over the last 12 months, despite a fall in share price (see box), his wealth has increased by 11 percent (which amounts to $180 million), pushing up his rank a further four notches to No 61 on the 2016 Forbes India Rich List.

But Mehta is shy of flaunting his wealth. He prefers to travel in the ubiquitous multi-purpose vehicle Toyota Innova—a popular car in the taxi industry—rather than a bullet-proof Mercedes-Benz or Rolls-Royce. He also prefers regular commercial flights to a private jet. “I don’t want to buy something just for the purpose of showing off. The day a private jet becomes an absolutely necessity, without which I cannot survive, only then will I look at it,” he says.

The only time when Mehta splurged on a trophy asset, and grabbed headlines, was in late 2011, when he bought the iconic Brindavan Hotel property in Bengaluru’s central business district of MG Road. Mehta forked out close to Rs 100 crore for the property that stands on less than an acre, with plans to build a family home.

“He [Rajesh] has been a raging bull in the gems and jewellery export sector,” says C Vinod Hayagriv, managing director of C Krishniah Chetty & Sons Pvt Ltd, a leading heritage jewellery retailer in Bengaluru.

But despite Mehta’s success in the gold trade, he has faced his share of adversity. There are multiple reports that detail how various state authorities have raided the company premises with regard to cases of tax evasion, and have questioned its trade-related activities. Mehta, however, maintains that the company is above board and transparent in all its business activities. “Their [Rajesh Exports’] chequered history has been intriguing,” adds Hayagriv, who is also the chairman of the legal committee of the All India Gems & Jewellery Trade Federation.

Laying the foundation

Mehta’s parents had relocated from their hometown Rajkot in Gujarat to Bengaluru in 1946-47. His father Jaswantrai Mehta traded in semi-precious stones, and was working for his cousin in Gujarat. About 25 years later, he branched out on his own and set up Rajesh Diamond Company, which continued to trade in semi-precious stones.

Despite having four sons—Bipin, 64, Prashant, Rajesh and Mahesh, 44—he chose to name his business after his third-born. “An astrologer from Bengaluru told my father that this boy [Rajesh] will give you the maximum benefit,” recalls Mehta. Since then, all business ventures by the family have been named after Rajesh Mehta. However, Mehta was never groomed to take over the family business.

“Rajesh was brilliant in studies and his goal was to become a doctor, as our family wanted him to become one,” says Prashant, who has been working alongside Mehta since 1982. “He is a thinker and plans for the future. I’m into execution.”

But instead of pursuing medical education, Mehta, who didn’t even join college after completing his schooling, believed that the jewellery business would be his calling. “Most people in my community are in some business or the other. Somewhere this fact did play on my mind,” he admits.

The two brothers, however, did not see a future in scaling up their father’s business. Instead, they approached their eldest brother Bipin, who was working in a bank, for a loan of Rs 1,200 to start trading in silver jewellery. With this money, they went to Chennai and bought the jewellery. “We took this to Rajkot and sold it to our relatives,” says Mehta, recounting how they made a neat profit by selling their stock for Rs 3,500. Slowly, their focus shifted from selling jewellery to relatives to selling it to retailers and wholesalers in Gujarat. But that wasn’t enough.

With the money they earned, they bought silver jewellery from Gujarat to sell to retailers and wholesalers in Bengaluru, Chennai, and Hyderabad. In effect, the brothers were trading in jewellery designs of different ethnic Indian cultures. “We used to take the southern designs and popularise them in Gujarat, and vice versa,” says Mehta. “It was like idlis being sold in Gujarat they may not become a staple diet, but they will become a fancy food item, which will be had once in a while.”

Soon, the brothers were trading in jewellery worth Rs 1 lakh and the business was formalised under an entity called Rajesh Art Jewellers. The business was further bolstered by their decision to barter their goods. “We used to barter the Bengaluru goods for the Rajkot goods and vice-versa,” recalls Prashant. The barter network was then extended, whereby jewellery from Rajkot was exchanged for that made in Mumbai, which in turn was bartered for jewellery from Hyderabad. “With every barter cycle, we would increase our capital base by 50 percent,” says Prashant, adding that Mehta and he would take turns to sleep while on long bus journeys between cities. “All our capital was in our bag.”![mg_91037_rajesh_mehta_280x210.jpg mg_91037_rajesh_mehta_280x210.jpg]() Going for Gold

Going for Gold

But silver jewellery was not as attractive as gold and the Mehta brothers were hungry for more.

By the end of 1984, they got a licence under The Gold (Control) Act of 1968 to trade in gold jewellery. However, Mehta had bigger dreams: He wanted to set up a manufacturing facility of his own, rather than just trade in gold jewellery. There was, however, a roadblock to his aspirations.

Under The Gold (Control) Act, no company could buy, store, and manufacture gold for domestic consumption. [The manufacturing of gold in the country at that time was largely in the unorganised sector, where the metal was either recycled or smuggled. The Act was repealed in 1990.] But Mehta found a way out: “If you wanted to export, you could manufacture in India. The Reserve Bank of India would give you gold, which could be manufactured for exports only.” He grabbed the opportunity, and in 1989, set up a small manufacturing facility with around 10 workers in the garage of his home in RT Nagar, Bengaluru.

This was the birth of Rajesh Exports. By 1992, the firm’s export business was Rs 2 crore, with markets in the United Kingdom, Dubai, Oman, Kuwait, the US, and Europe. In 1990, the company also set up a standalone retail store branded as Rajesh Jewels, in Batavia Chambers, which now houses Rajesh Exports’ head office. In the last three years, the store has changed to a new brand identity of Shubh Jewellers. Currently, there are 80 Shubh stores in Karnataka.

“Expansion is in our blood. We can’t sit quiet, we are always doing something,” says Mehta, who took the company public in 1995 and raised Rs 10 crore. By this time, the company’s export business had grown to Rs 35 crore. By 1998, exports had reached Rs 120 crore. Once again Mehta had a bigger vision for the company: To build a 250-tonne manufacturing unit in Bengaluru. “He always thinks out of the box,” says Prashant, who was not convinced about setting up such a large unit. But the company operationalised the facility in 2001-02, on a 10-acre plot in Whitefield, now a major IT suburb of Bengaluru.

As of today, only half of the facility’s installed capacity is being utilised. Mehta says he built it with a 20-year vision in mind. Over the years, the facility has seen the addition of a research and development unit that focuses on jewellery designs, new manufacturing methods, and saving waste. A machine manufacturing unit has also been set up on the campus.

Looking back, Prashant says, “This facility has been our trump card and has changed our fortune.” Because of its size, he adds, “we are able to deliver orders very fast and build large wholesaling capacities across the world.” After a year of the facility becoming operational, revenue catapulted to Rs 1,000 crore from Rs 200 crore. In 2007-08, the company set up another manufacturing unit, with an installed capacity of 100 tonnes per annum in a special economic zone in Kochi. And in 2013, it set up a gold refining facility in Uttarakhand. Put together, the Uttarakhand and Valcambi facilities can refine over 2,400 tonnes of gold a year. “I used to question his decisions earlier, but now I have stopped. His vision is five-fold, and he has never gone back on his words,” says Prashant.

Future perfect?

“Over the next 10 to 12 years, we are confident that our retail business, which is 1 percent [of consolidated revenue] now, will constitute around 90 percent of our total turnover,” says Mehta, who is aiming to open 2,500 stores across India within that time. He is also looking to roll out an ecommerce retail venture for gold jewellery in a year from now. Besides, plans are afoot to enter the airport duty-free retailing sector. “Our net profit margins are about 0.70 percent and we are working towards a 15-fold jump, which we are going to achieve through retail,” is all that he says about his plans. The company’s end-to-end capabilities—from mining operations in Africa to retailing—are definitely an advantage in offering better prices.

Their mining capabilities, which are expected to increase, give them access to raw material at cost price their refining capabilities ensure negligible premium on refined gold and their manufacturing capabilities ensure zero wastage costs. So, if rivals are selling jewellery at a 25 percent premium, Rajesh Exports is in a position to disrupt the market.

According to Hayagriv, one weakness of the company has been that it, “has excelled and has grown on the borderline of regulation exceptions.” Hence, he says, “A transformation to mainline will help the company.”

But brand expert Raghu B Viswanath believes Shubh has not made much headway in jewellery retail in the last four years. “I would still say that it is a larger mom-and-pop store rather than saying that he [Rajesh Mehta] owns a retail brand of reckoning,” says Viswanath, chairman of Vertebrand, a brand value advisory and marketing consultancy firm.

There are many commodity players in India who have entered the retail arena of late. Although retail has given them visibility, their personal wealth continues to be generated mainly from their core trading activities. “For me, a successful entrepreneur is not one who has been very smart in business deals and therefore has created a lot of personal wealth,” says Viswanath. “A successful entrepreneur is one who has built an institution and a legacy.” Does that not make Rajesh Mehta a great entrepreneur? “Time will tell,” adds Viswanath. “He’s young, his retail venture is just four years old, so one has to wait and watch.”

This, of course, is in today’s context. One year from now, the narrative could completely change, given Mehta’s penchant for thinking out of the box.

Rajesh Mehta, founder and executive chairman of Rajesh Exports Ltd, wanted to become a doctor till he realised that the jewellery business was his calling

Rajesh Mehta, founder and executive chairman of Rajesh Exports Ltd, wanted to become a doctor till he realised that the jewellery business was his calling

Going for Gold

Going for Gold