India can't be a Jugaad Economy Forever

India has to implement key reforms in at least three areas—energy, land and labour—to get its economy back on track. It also needs to expand the ambit of economic and political freedom

World Bank data suggest that India was ninth in the world in terms of new businesses registered in 2011. The cost of starting up a business is still high but it has steadily fallen from 70.1 percent of per capita gross national income in 2008 to 49.8 percent in 2012. The time taken to start a business in India has fallen from 33 days four years ago to 27 days in 2012. Newly released Planning Commission numbers show that India reduced extreme poverty by 15.3 percent in seven years that is, 138 million people were lifted out of absolute misery between 2004-05 and 2011-12. In the same period, millions of Indians moved up the social ladder to be counted as middle class. Sales of luxury cars, designer clothes and high-tech gadgets have been growing at 15-20 percent. A Bain & Company report on luxury has been quoted as estimating the number of people with disposable incomes of over $100,000 to top 132,000 in 2013, up 60 percent since 2006.

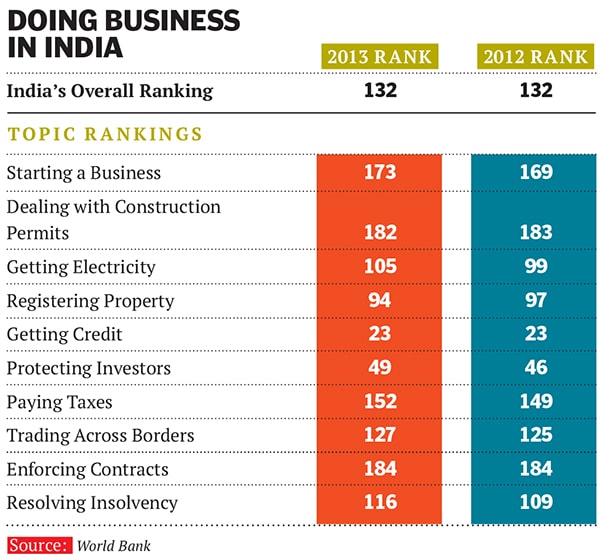

So, is it time to bring out the bubbly? Not quite. In a competitive world, you gain only when you outpace your rivals, and not merely by doing better than before. Despite all the improvements mentioned above, India ranks a lowly 132 in the World Bank’s list of countries for ‘Ease of Doing Business’. Growth has stagnated at a decade’s low of near 5 percent. Reflecting the economic weakness, the rupee is plumbing record lows against the dollar. Industrial growth is barely above zero. Consumption demand continues to slump and investments have ground to a halt while retail prices continue to rise. According to Reserve Bank data, private listed non-finance companies’ sales grew just 4.1 percent in the March quarter. These companies are slowing production and cutting costs. India has the largest number of young people among major economies but does not have the mechanisms in place to train them or find decent jobs for them.

A recent survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) for CNN-IBN shows that the number of people who are satisfied with their personal financial situation has dipped over the past two years. The dissatisfaction was most pronounced among the middle class. About a third of the 19,062 surveyed believed the country’s economic condition was “so-so”. Nearly half of those felt that the gap between rich and poor has widened. India’s Gini coefficient (which measures income distribution) was 33.9 in 2010 compared to 30.8 in 1994, indicating that income inequality has been rising.Is the India story petering out?

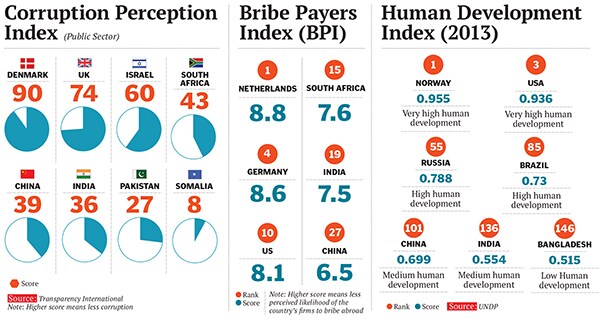

As the world was reeling under the impact of the US meltdown followed by Europe five years ago, the Indian and Chinese economies remained beacons of growth. After a mild slump in 2008-09, India quickly recovered the next year. Elections brought the United Progressive Alliance back to power with an improved mandate and the latter assumed that nothing more needed to be done. Hubris set in. It didn’t help that the prime minister played the reluctant leader bogged down by ‘coalition compulsions’. The euphoria soon paved way for despondency as scams rocked the government, forcing the administration deeper into inaction. The economy is now teetering on the brink because of faulty economic policies, endemic corruption, poor governance and crony capitalism that concentrates rather than spreads wealth. The government has lost political capital and is resorting to fiscally dangerous populism in a bid to get re-elected.

It is time to push the frontiers of economic and political freedom once more. Else, we’ve had it.

If 1947 brought us political freedom, we took the wrong road to prosperity by tying the hands of productive forces in the licence-permit-quota raj. That knot was untied in 1991, when the economy was opened up and business freed. That burst of economic reforms opened the field to new competitors and widened the pool of wealth creators. But over the last nine years, the pool has remained stagnant, enabling only a limited number of businessmen to remain successful. Even though a second stage of economic reforms has been awaited and demanded for several years, it has not happened.

Economists like Columbia University’s Jagdish Bhagwati have long argued for it. “Further liberalisation of trade in all sectors, substantial freeing up of the retail sector, and virtually all labour market reforms are still pending. Such intensification and broadening of Stage 1 reforms can only add to the good that these reforms do for the poor and the underprivileged,” Bhagwati told Indian Parliamentarians three years ago.

But the din of multi-crore scams, scandals and a dysfunctional parliament has buried the chances of any near-term improvement in the business climate.

The big drag

So what can be done? Although there are several areas that are crying out for policy reform and entrepreneurial freedom, three major ones—land, labour and energy—are creating the biggest bottlenecks to the India growth story. None of the problems in the three areas has easy answers.

The Confederation of Indian Industry has presented a list of 62 stalled infrastructure projects—each worth Rs 1,000 crore or more—to the Project Management Group in the Cabinet Secretariat for fast tracking. Of these, 35 are power projects and 11 are for construction of roads and highways. Most of these projects are stuck because of lack of environment approvals, state level clearances or inability to acquire land. As on May 1, 2013, nearly half of 566 Central sector projects (of Rs 1,500 crore and above) got delayed due to problems such as lack of clearances (mainly environment-related), inability to acquire land and insurgency. The cost overruns for these are estimated to be around 18.2 percent, the Reserve Bank of India says.

Many of these projects would displace people, destroy forests and overrun fertile farmlands, all politically sensitive issues. Some industrialists have given up. South Korea’s Posco and Arcelor Mittal have quit after trying for several years to set up mega steel plants in Odisha. The state is set to lose lakhs of crores in investments. Industries are also struggling to find skilled workers. Thousands of students passing out of schools and colleges are unemployable. The government’s skill development policy is in a shambles and what may have been a demographic dividend now threatens to become a burden.

Some of the issues are vexed but some are easily addressed provided there is a committed leadership. Institutional structures need to be reviewed and predictability and consistency restored to government policy. In the following pages, experts in various fields analyse some of the key problems facing the country and what can be done to address them. India cannot afford to waste its entrepreneurial energy and spirit of innovation. The time for jugaad, in the multitudinous meaning of the word, is over.

First Published: Aug 19, 2013, 06:39

Subscribe Now