The freedom to 'Make In India'

India's entrepreneurial and startup culture has yet to reach its full potential, but the report card is good, for the most part

Infosys co-founder and former CEO NR Narayana Murthy has often narrated the tale of his celebrated entrepreneurial journey. One anecdote stands out: He had to wait for an entire year to get a simple telephone connection, and three years for a licence to import computers. Murthy, who founded one of India’s largest software services firms in 1981 with six colleagues and seed capital of $250 that he borrowed from his wife, has used this story with great effect to demonstrate just how adverse the environment was for a young professional trying to venture out on his own more than three decades ago.

Much has changed in India since then, especially after the economic liberalisation in 1991. Fixed-line phones, wireless smartphones, laptops and tablets offering voice and data connection are readily available and at competitive rates. Not only has the improvement in connectivity and communications aided traditional businesses such as manufacturing, it has also spurred an entire generation of new-age enterprises: Ecommerce firms that leverage technology to reach customers in areas that weren’t physically accessible before.

The environment for entrepreneurial freedom in India—where an individual or a group of individuals can come together and start a business of their choice and grow it in scale—is far more conducive now than when Murthy was starting out.

Not only has technology made life easier, enterprises are attracting more of private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) funding as they seek to grow. According to the India Private Equity Report 2015 by consulting firm Bain & Company, the total value of PE and VC deals in India grew by 28 percent year-on-year to reach $15.8 billion. This is nearly six times the value of PE/VC deals reported in 2005.

Evolving public sentiment backs this data. Harsh Goenka, the 57-year-old chairman of RPG Enterprises (a $3.6 billion-conglomerate with interests ranging from automotive tyres to information technology), says that in recent years, there has been an acceptance and celebration of entrepreneurial spirit in India. “We have made a lot of progress from the days of the licence raj. However, there are many obstacles that still remain, including bureaucracy, tax and corruption,” says Goenka, a second-generation industrialist.India’s budding entrepreneurs agree with him. Pranshu Pandey, the 26-year-old co-founder of language learning startup, CultureAlley, describes a growing and vibrant ecosystem, in terms of both VC funding and support services. She believes that the situation today has improved from what it was three years ago when she started out. “In 2012, getting seed funding was difficult. We were lucky since we had family support, but I would think to myself that there could be so many brilliant business ideas that soon-to-be graduates from various engineering or business schools may have, which won’t materialise due to lack of funding. [In those days] investors wanted the business to gain some sort of traction before committing capital,” says Pandey, whose startup helps people learn languages through audio-visual and interactive lessons via a digital app.

And while the situation may have improved, it is still behind Silicon Valley in the US, where investors will back entrepreneurs more readily even if their venture is only at the idea stage.

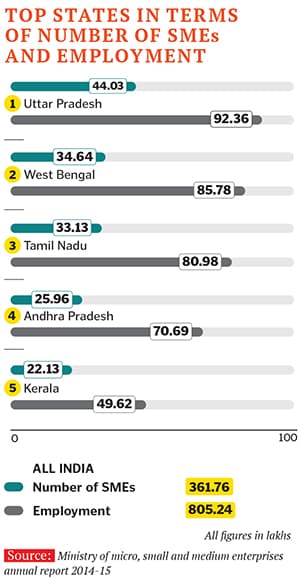

Nafisa Radiatorwala, founder of Nature’s Glow, which makes ayurvedic skin and hair-care products, and exports them to the US, believes that the introduction of policies like the Prime Minister’s Employment Generation Programme that offers capital subsidies—from which she benefitted after the scheme was launched in 2008—have made a difference. “When we were starting out [in 2006], even if there were some policies on paper, their implementation wasn’t proper. Credit facilities were also very difficult to come by. Banks were averse to lending to startups,” Radiatorwala says. “Even if they did, it was against collateral, which the entrepreneur would find difficult to furnish.” Today, there are more schemes to foster new businesses, including those that encourage women entrepreneurs, especially in rural India.That said, India still lags behind the rest of the world: According to the Global Women Entrepreneur Leaders Scorecard released in June 2015 at the Dell Women’s Entrepreneur Network Summit in Berlin, India was scraping the bottom of the barrel at the 29th rank among 31 countries. India’s internal surveys are equally damning. A 2014-15 annual report by the ministry of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) shows that a mere 7.36 percent of all MSMEs in the country are owned and operated by women.

The writing on the wall cannot be clearer: Technology and access to VC funding has improved considerably and is gaining more ground, especially over the last few years, but there is plenty of room for improvement.

Time to Cut the Red Tape

Impediments such as access to bank credit and multiple regulations—be it to simply start a company or file tax returns—are preventing the Indian entrepreneurial spirit from realising its full potential. Fact is, most fledgling businesses are struggling to secure bank credit. “The ability of small businesses to attract bank funding is constrained. They are required to fulfil many stringent criteria such as furnishing collateral and guarantees, which only those with access to family wealth can do. The others simply get excluded,” says Laveesh Bhandari, chief economist of Indicus Analytics, an economic research and data analytics firm owned by Nielsen India.

The other major challenge is multiple regulations. A report by the World Bank Group titled ‘Doing Business 2015’ compares regulations for domestic businesses in 189 countries. At 142, India falls in the bottom half of the list as far as ease of doing business is concerned. What’s worrisome is that compared to an earlier instalment of the report, India has slipped two positions (after adjusting for some data correction and change in methodology).

The report throws up some interesting data. For instance, it takes an average of 11 procedures and 28 days to start a business in India, whereas it takes only half-a-day and one procedure to start a company in New Zealand. When it comes to the ease with which an enterprise can pay taxes in India, the country ranks 156th. A company spends around 243 hours in a year filing tax returns and has to make around 33 tax payments. Compare this with Hong Kong, which requires only three tax payments to be made annually. In Luxembourg, firms spend only 55 hours a year filing tax returns.

Pandey of CultureAlley points out that even the time taken to receive funds secured from investors in the bank after meeting all the regulatory requirements can be long. “Sometimes it may take as long as three months, and receiving timely capital infusion is crucial for the success of a startup in its growth phase,” she says.

Another hurdle is complex labour laws, which are particularly relevant to manufacturing companies. “Our labour laws, we have around 44, are complex and a great impediment to growth. To expect a small enterprise to take care of these issues is a tall order,” says Goenka. The labour laws fail to factor in the realities of operating a business. In a February 2015 guest post on the Financial Times blog, Bibhas Saha, professor at Durham University Business School, writes that India’s archaic labour laws make it difficult for enterprises to restructure themselves efficiently, especially in instances where they aren’t doing well.Goenka adds, “There should be progressive laws on industrial relations, wages, social security, safety, health and hygiene. Entering or exiting businesses should be made easy (from the standpoint of managing labour-related issues), so if an entrepreneur fails, he or she can move to a new venture.”

Though the good news is that entrepreneurial freedom in India has grown in strength, despite these hurdles, it doesn’t manifest evenly across the country, with some states doing better than the others.

Report Card

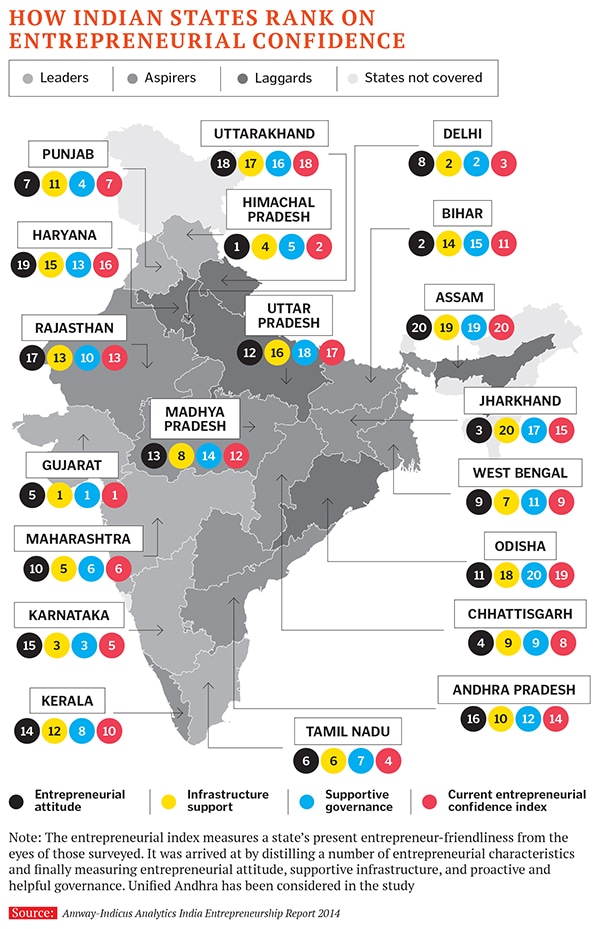

A joint study conducted by Indicus Analytics and direct-selling consumer goods company Amway, titled ‘India Entrepreneurship Report 2014’, finds that Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka rank among the highest on the current entrepreneurial confidence index. Parameters include the entrepreneurial attitude of the people, infrastructure support and supportive governance. Haryana, Uttar Pradesh (UP), Uttarakhand, Odisha and Assam are the bottom five states on this list.

The study, which surveyed over 5,000 respondents across 50 cities in 20 Indian states, finds that most of the economically developed states appear at the top of the list. They offer an enabling environment and a growth-oriented economy for entrepreneurs to thrive in.

It’s worth noting that those at the bottom of the pack—Bihar, Assam, Jharkhand, and West Bengal—ranked high in terms of entrepreneurial attitude, referring to the willingness of people in these states to do something on their own. “Lack of livelihood opportunities may significantly trigger openness toward entrepreneurship,” the India Entrepreneurship Report states. “[But] many of the states that have an advantage due to their open mindedness towards entrepreneurship do not have other facilitating factors to translate their latent entrepreneurial potential into new startups.”

Bhandari says top performers are represented by governments that have consistently and constructively engaged with industry to understand their needs and challenges, and address them. If such models can be replicated across the states, India may see itself reaping the rewards for years to come.  The Road Ahead

The Road Ahead

From Ghanshyam Das Birla, who founded one of India’s first manufacturing businesses in 1919, to Sachin and Binny Bansal, who built one of the most well-known ecommerce companies, Flipkart (in 2007), there is no denying that Indians have a tradition of entrepreneurship. But to unleash the full potential, the government needs to take care of the challenges that threaten to thwart the country’s growth story.

The current government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, appears determined to create entrepreneurs of the future, both, in the services sector (through campaigns like ‘Digital India’) and in manufacturing through the ‘Make in India’ initiative. Several schemes aimed at making it easier to do business—like a single window clearance system—have either been put in motion or are on the anvil.

While trying to make India a more entrepreneur-friendly country, the administration could do well to look at its peers in Asia like Singapore, which has become a hub for startups on account of policies offering substantial tax incentives to startup companies.

As Goenka puts it, “To promote entrepreneurship, we need to promote ideas, provide access to low-cost funding, mentorship, guidance, a friendly tax regime and skilled workforce.” To realise this dream, the people, the state and its political and business leaders need to find a common ground.

First Published: Aug 17, 2015, 06:57

Subscribe Now