Tara Thiagarajan Wants the Poor to get more out of their Micro Borrowings

The answer she says lies in better networking just like in the human brain

In June last year, Chennai-based Madura Microfinance posted a recruitment ad for post-doctoral students who could work efficiently with large datasets—the kind used by researchers in engineering, science and economics. The project involved reconstructing the trade and communication networks of rural South India from large datasets.

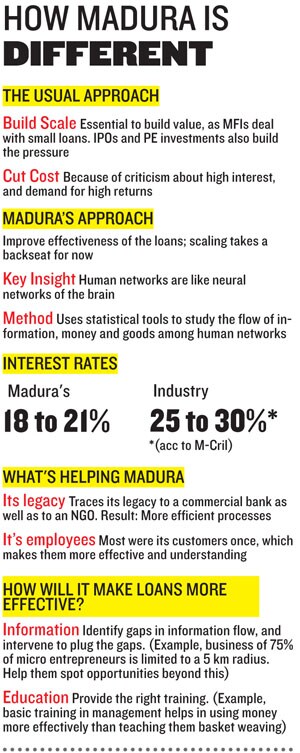

While the beleaguered microfinance companies are desperately seeking to control costs, standardise processes, explore new markets and battle regulatory changes, why was Madura looking for post-doctoral researchers?

Because its Chairperson Tara Thiagarajan believes that microfinance institutions (MFIs) have been pursuing the wrong goal. Instead of scale, they should be looking to make loans more effective. That means borrowers should get more out of their borrowings. Along with credit, they should also get the tools and the benefits of a large network to make the most of the credit.

The pursuit of scale—regardless of the borrowers’ capacity to repay, and at the risk of geographic concentration—has turned out to be the sector’s undoing. Thiagarajan is also not impressed with the past “achievements” of microfinance—with stories of how a young mother could buy notebooks for her children, or how a household could buy an additional cow in just one year. For a phenomenon that promised to lift people out of poverty, microfinance seemed to do too little.

She is drawing on her background as a neuroscientist to find the solutions.

The scion of a successful South Indian business family, she studied at the Kellogg Graduate School of Management at Northwestern University. While pursuing an MBA, she was also drawn to study how the brain works. Eventually, she did a PhD at Stanford, and ended up in the National Institutes of Health in the US.

Then in 2004, her father K.M. Thiagarajan, who was running Mudra, suffered a stroke and asked her to help him out. Initially, Tara divided her time between India and the US, where her family lived. In 2007, she decided to shift base to India, and devote most of her time to microfinance.

Luckily for her, she inherited a strong MFI. In 2007, Forbes had ranked it among the 50 top MFIs. It’s an offshoot of the Bank of Madura, which ICICI Bank acquired in 2000. So, it had processes in place that keeps its costs low. Its operating costs are 3.5 percent, its interest rates vary between 18-21 percent and repayment rate is 99 percent.

When its customer base reached 4 lakh in 2008, Thiagarajan pressed the pause button on scale, and began looking for ways to make the loans more effective.As a scientist, she had studied how electrical signals move between neurons. Applying that to her business, she sees society as a network of networks. Instead of electrical signals, there was flow of goods, money, and most importantly, information.

It’s a systems approach to microfinance. You recognise the market is made up of many parts, and that a change in one part can have a non-linear, more than proportional impact on others,” says Mohan Eddy, a consultant who is helping Thiagarajan put IT systems in place at Madura.

High-level thinking in the brain is characterised by weak links. In general, strong links are good for well-defined, routine tasks and weak links are needed for complex tasks that require connecting unrelated fields. In sociology, strong links help in doing the routine tasks, while weak links come into play if one is looking for new opportunities and growth.

In human societies, studies on networks suggest that rather than the first degree connections, the second or third degree connections—that is, not the people you know directly, but the people your contacts know—are more useful in finding jobs or business opportunities. Weak links matter.

When Thiagarajan looked at her customers, their business seemed to be characterised by strong links. A survey revealed that for about three quarters of micro entrepreneurs, the source and the market were limited to a 5 km radius. Often, the business was confined to a few streets, hardly conducive for growth.

The solution: Facilitate channels that would let them spot opportunities beyond their neighbourhood. It demands a mix of training and market facilitation. “There is no point in teaching them how to weave a basket, when there is no demand for baskets. Entrepreneurs need a different set of skills. How to identify demand, in the first place,” says Thiagarajan.

That’s why she’s focussing on collecting data related to demographics, networks, mobility and flow of goods and information among her 4 lakh customers. Hence the post-doctoral scientists trained in data collection and research.

The goal is to develop models that will help in understanding the structure and dynamics of the network. This will help in making more relevant training programmes and mobile services that would have immediate impact—and ultimately help customers make better use of credit. From a business perspective, it will help Madura get a nuanced understanding of the market, and do better segmentation.

“We call it the Madura Experiment. It’s still in the early stages, but it will have a lot of impact on what we do, and how we do,” she says.

The commonly used metaphor—the bottom of pyramid—gives an impression of strength and stability. Yet, a closer look would reveal insular groups, fragmented markets, and stunted flow of information. “It resembles the disc of a vortex than the bottom of the pyramid,” says Thiagarajan.

In contrast, things at the top are characterised by higher interconnectedness and better flow of goods and information. That’s the reason why money is more efficient at the top (and why the rich tend to get richer). In the end, that’s what she hopes will happen to her customers too. Also, the urban poor are more closely networked and have better livelihood options. The rural poor don’t.

“The key is to understand how things work. It may take time. In fact, it does take a lot of time. But, if you want to see things change, if you want to add real value, you should be prepared to spend time to dig deep, and to understand,” she says.

First Published: Mar 15, 2012, 06:55

Subscribe Now