Laurus Labs: A hot startup in the pharma sector

Although a chemist by profession, Satyanarayana Chava's astute business sense is reflected in the success of his Hyderabad-based pharmaceutical startup

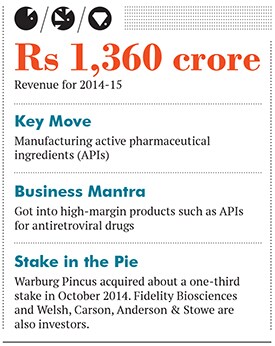

When Dr Satyanarayana Chava started Laurus Labs in 2007, he invested nearly Rs 60 crore of his own money into it. His confidence in its success was neither bravado nor bluster, but defined by his knowledge of the pharmaceutical industry. Eight years on, the Hyderabad-based company is on track to reach revenues of Rs 2,000 crore by the end of FY2016.

Chava, now 52, has more than two decades of experience in the pharmaceutical industry in his last job, he was chief operating officer (COO) of the successful startup, Matrix Laboratories. Of his 10 years there, he says with pride, “I never skipped a promotion and got to work in all departments.” His dedication, coupled with a sound understanding of what it takes to start a pharmaceutical company, is what makes Laurus Labs among the hottest startups in this sector.

Initially, Chava planned the business around research and development (R&D). He wanted Laurus Labs to focus on contract research and make money from royalties. “In India, companies start with manufacturing and then get into R&D,” he explains. “I did it the other way round.” He focussed his fledgling company’s resources on developing formulations for medicines, and licensed them to other pharmaceutical players. In the early months, Laurus Labs had 10 people in manufacturing and 300 in R&D.

In June 2007, Aptuit, a US-based contract research organisation (CRO), signed it on for a $20 million (then Rs 80 crore) contract. But despite this injection of funds, Chava was unable to sustain his original idea of developing technologies for other companies. At the time of the Aptuit deal, Laurus Labs’s annual revenues were not even $20,000 (Rs 8 lakh at the time). In 2008, Chava decided to start manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), which, as the name suggests, are chemicals or key ingredients in drugs required to make the medication work. His early investment into R&D benefitted Laurus Labs it maintains a large repository of research-based knowledge that forms the bedrock of any successful pharmaceutical business.

Today, it is a key manufacturer supplier of APIs and holds its own against better-known competitors like US generic drug giant Mylan, which, incidentally, acquired a controlling stake in Matrix around the time Chava founded Laurus Labs. It has also carved a niche for itself by supplying antiretroviral or ARVs (used to fight infections caused by retroviruses like HIV) and oncology drugs. And despite being a relatively new player, its clients include giants like Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries and Merck.

The person behind it

A Master’s degree in chemistry was never on the cards for Chava. In the early 1980s, the best students usually studied physics, and he had planned to do the same. But when he went to his college in Amravati (Andhra Pradesh) to enroll, his elder sister’s friend suggested he study chemistry too. Chava took up the subject on a whim. He ended up liking chemistry so much so that in his final year he topped his batch despite not having written one out of the four required papers. He went on to complete his PhD in the subject in 1991.

Upon graduating, he was hired by Ranbaxy Laboratories in Delhi as a researcher. In those early years itself Chava knew he’d spend a lifetime in the industry. He enjoyed the work and gained valuable experience as a young researcher in what was then India’s finest pharmaceutical company.

But through his years in the industry, Chava was conscious of the fact that he needed to broaden his experience outside of research. His stint at Matrix Laboratories afforded him that opportunity. As it was a startup, he was able to rise through the ranks quickly and got the opportunity to work in key departments from sales and marketing to finance and accounts. Within eight years of joining Matrix, he became its COO.

This experience was to come in handy when, due to differences with the board—he refused to elaborate on this—he decided to leave Matrix and set up Laurus Labs. And though he is the company’s chief executive officer (CEO), Chava remains true to his calling as a chemist. He has strived to build an organisation that is not very hierarchical. It is not uncommon to see him interacting with the chemists in the company and discussing formulations with them—something unheard of in an industry where most CEOs are from a sales and marketing background.

Why it is a gem

Laurus Labs is targeting a Rs 2,000-crore topline in eight years. Even in the profitable pharmaceutical business, such a rapid pace is not seen very often. This success can be attributed to Chava’s decision to develop APIs, through which the company is able to enjoy higher margins compared to an average generic drug manufacturer. APIs generally constitute between 20 and 35 percent of the total cost of a drug, but the ones that Laurus Labs develops, like ARVs, constitute 70 to 75 percent of the cost of the drug.

One indicator of the company’s success is the average revenue earned per employee every year, which stands at $115,000 (about Rs 75 lakh). An employee’s annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebidta) is $20,000 (Rs 12 lakh). “This is on par with what the top five Indian generic companies in the world make,” says Chava.

Why it was hidden

Apart from the fact that Laurus Labs is a relatively new player in an already crowded market, it does not manufacture over-the-counter products and follows a business-to-business model. But investors always on the lookout for the next new kid on the block were aware of its potential.

In October 2014, private equity (PE) firm Warburg Pincus picked up a significant stake in the company for $92 million (then Rs 560 crore). “What excited us about Laurus Labs was the company’s relentless focus on innovation and quality to become the most efficient manufacturer in its products. This has made them a market leader in some products in a relatively short period of time,” says Narendra Ostawal, managing director, Warburg Pincus India.

Other PE players who have made smaller investments in Laurus Labs include Fidelity Biosciences and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe. Chava declined to divulge his or the investors’ stakes in his company. He did, however, say that Laurus Labs has enough cash flow to fund its expansion over the next three to five years.

Risks and challenges

For now though, Laurus Labs is still a fledgling company with about 20 customers the top 10 make up 80 percent of its sales. Chava admits that one client accounts for a quarter of his company’s sales. While acknowledging this risk, he says, “We haven’t lost a single customer and are growing with them.”

There is also the risk of product concentration, but Laurus Labs periodically reviews its portfolio and is getting into newer areas like APIs for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Regulatory risk is always a clear and present danger for pharmaceutical companies with inspections by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) haunting even India’s drug giants. “We were very clear that we wouldn’t have a different plant for sales abroad and a different plant for sales in India. Quality has to be built into the organisation,” says Chava, adding that the company has not received an adverse remark during any of the FDA inspections.

Chava has big plans for his company, which, is still seen primarily as an API manufacturer. This will change as Laurus Labs is planning to also become a consumer-facing business by getting into areas like manufacturing health care supplements. Active plans for this are already under way. And while he may be a chemist by profession, Chava is also a canny businessman. He knows that such a move has the potential to increase the company’s valuations. Only then will Chava consider an initial public offering.

First Published: Sep 14, 2015, 06:00

Subscribe Now