Kolkata's Senco Gold: Banking on franchises for expansion

From just three jewellery stores in the early 90s, the company now has nearly 100 across the country today

Shaankar Sen, managing director, and his son Suvankar, executive director (right) of Senco Gold and Diamonds

Shaankar Sen, managing director, and his son Suvankar, executive director (right) of Senco Gold and Diamonds

Image: Subrata Biswas for Forbes India[br]It has been a long journey for Shaankar Sen of Senco Gold and Diamonds.

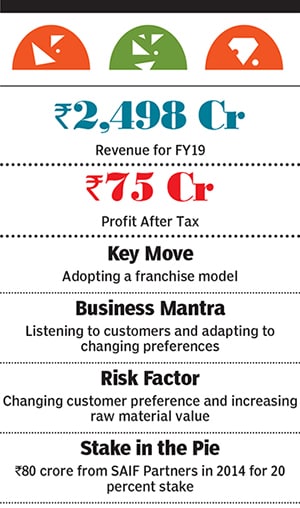

From owning just three jewellery stores in Kolkata that he inherited from his father in the early 1990s to nearly 100 across the country today, the 62-year-old has certainly come a long way. In fact, for the bespectacled businessman—who dropped out of his post-graduate degree in commerce from the University of Calcutta to help his ailing father run their jewellery stores—the moment of reckoning could have been this year, if not for Nirav Modi, the fugitive diamantaire.

Senco had planned its initial public offer (IPO) to raise ₹600 crore from the market, before withdrawing it in March. “The sentiment in the market is dull due to Nirav Modi and the apprehension about jewellers,” Shaankar says. “Then, we also saw the tanking of PC Jewellers on the stock exchanges. That’s why we have pushed the IPO.”

But Shaankar, who works out of his office on the 10th floor of a commercial building on South Kolkata’s AJC Bose Road, isn’t perplexed. “We have done our part in building our company,” he says. “We will wait for the right time. It’s a milestone in our journey.” Shaankar’s company, Senco Gold and Diamonds, is the largest gold jeweller in eastern India and has expanded its footprint across 14 states through a mix of franchise and self-owned stores.

Today, Shaankar and his son Suvankar (who joined the business in 2008) are leaving no stones unturned in adapting to the change. “Of course, we will open more stores,” says Suvankar, the executive director. “But we are designing a customer experience for the future.”

From Dhaka to Durgapur

Senco Gold and Diamonds traces its roots to erstwhile East Bengal. Shaankar’s ancestors had set up a jewellery business in 1938 in Dhaka but had to leave that behind during the partition in 1947, when East Bengal became a part of Pakistan. Overnight, Shaankar’s father and his brothers migrated to Calcutta. Over there, the family engaged in bulk sales of gold before moving to retail and between 1950 and 1960 set up nearly 10 stores across the city. By 1962, however, due to a war with China over a border dispute, the government decided to introduce the Gold Control Act, which recalled gold loans given by banks and banned forward-trading in gold.

By 1968, Shaankar’s father split from the family to do business on his own, and in the process, received a store in the Bowbazar area of Kolkata. “At that time, if you wanted to set up one jewellery store, you had to take a licence from the central excise department,” says Shaankar. “A licence was issued after three years of persuasion.”

Thanks to goodwill and public relations—the only capital his father managed to earn, according to Shaankar—Senco opened two more stores between 1968 and 1972. By 1978, as his father’s health began to decline, he dropped out of his post-graduate studies to help his father run the business.

The big break came in 1990, when the government repealed the Gold Control Act and opened up the market. By 1994, since other members of the family also ran their gold business under the Senco brand, Shaankar established a separate identity with Senco Gold and Jewellery Pvt Limited. New Beginnings

New Beginnings

In 1998, when the company operated three stores with 45 employees, Shaankar dabbled with the idea of a franchise model. Back then, only the Tata Group had engaged franchises with its jewellery arm Tanishq, that too without much success. Shaankar’s model required a one-time fee and assurance that the gold at the stores would be exclusively sourced from Senco Gold.

“We opened our first franchise store in Durgapur [in West Bengal],” says Shaankar. “My customers were travelling between 100 and 200 km to buy jewellery. Because of logistics issues and financing constraints, franchising appeared to be the right mode.”

In 2008, Suvankar—who had a postgraduate diploma in business management from the Institute of Management Technology (IMT) in Ghaziabad—joined the family business and by 2010, Senco had expanded to 15 stores, all within the eastern region. Yet, in retrospect, the third-generation jeweller says the growth had been largely subdued compared to what they managed in later years.

Taking advantage of people’s growing per capita incomes and the economic boom, Senco had gone about opening up more stores its first store outside Bengal came up in New Delhi in 2008. By the time private equity major SAIF Partners pumped in ₹80 crore around 2014, Senco had already expanded to 59 stores. “If we put a finger on the reason behind the growth, it came because of the franchising model,” says Shaankar. “We have always believed that we must take care of the franchisees and their problems. ‘If they do well, we do well’ has been the mindset from day one.”

“You have to be with your customer,” he adds. “You have to keep your ears and eyes open, and see what the customer wants. And you have to act accordingly.”

Virtual Reality for the Millennial

Now, as smartphones and the internet take over shopping in India, the father-son duo at Senco doesn’t want to be left behind.

“It is an evolving business,” says Suvankar. “[Technology] is still nascent and investments are higher. But, at some point, it is going to work. Even with franchising, no other family jeweller had thought of it. We are a firm believer in technology.”

In the next five-six months, the company is planning to launch an interactive platform through which customers can assess their preferences and try them out virtually it will help the company take a step towards personalised shopping based on data collected over the years. Senco also retails its products on ecommerce platforms such as Flipkart and Amazon, which makes a marginal but growing contribution to the company’s revenue.

“They have the ambition to scale up to [being] a pan-India company,” Mridul Arora, managing director at private equity firm, SAIF Partners says. “They are a third-generation, family-run business with high governance standards and ethics. The franchise model that they work on has been very successful and that has been instrumental in strengthening the brand. Now, by calibrating technology, they could grow remarkably well.”

Even then, the company has some serious challenges to tide over. To begin with, it has to keep adapting to the changing needs of its customers and rising gold prices. “In jewellery, we see a new mindset among younger consumers—they don’t like the styles that were preferred by previous generations. So you need a huge amount of research and design experiments,” says Suvankar.

For now, the father-son duo are clear about where they want to take the company. “We are trying to make sure the business isn’t dependent on us alone,” says Shaankar. “There is a CFO and chief technology officer and we want to only set the vision and let the organisation run by itself.”

First Published: Aug 20, 2019, 09:37

Subscribe Now