Mind games: Startups ensure mental illness is not a lonely battle

With greater awareness, mental illness is now being treated seriously. And tech-based ventures in the space are lending a helping hand

Image: Shutterstock

Sachin Chaudhry was distraught to see his younger brother fight a lonely battle with schizophrenia. This was 1994 and there was hardly any awareness about mental health in the country. Being healthy was restricted to one’s physical and social well-being.

The experience prompted Chaudhry, 41, to set up TrustCircle in 2015. The startup uses mobile and artificial intelligence (AI) technology to improve emotional resilience. “I realised early on that there are clear gaps in India’s mental health care ecosystem, with a complete disregard for any preventive, participative or protective approach,” says Chaudhry, founder and CEO of TrustCircle. “Why do high-functioning adults not pay attention to our one critical organ: Brain?” he asks.

Chaudhry points out that since we don’t feel the pain of the trauma that the brain goes through, we stop giving enough importance to the vitals that keep it healthy: Emotions.

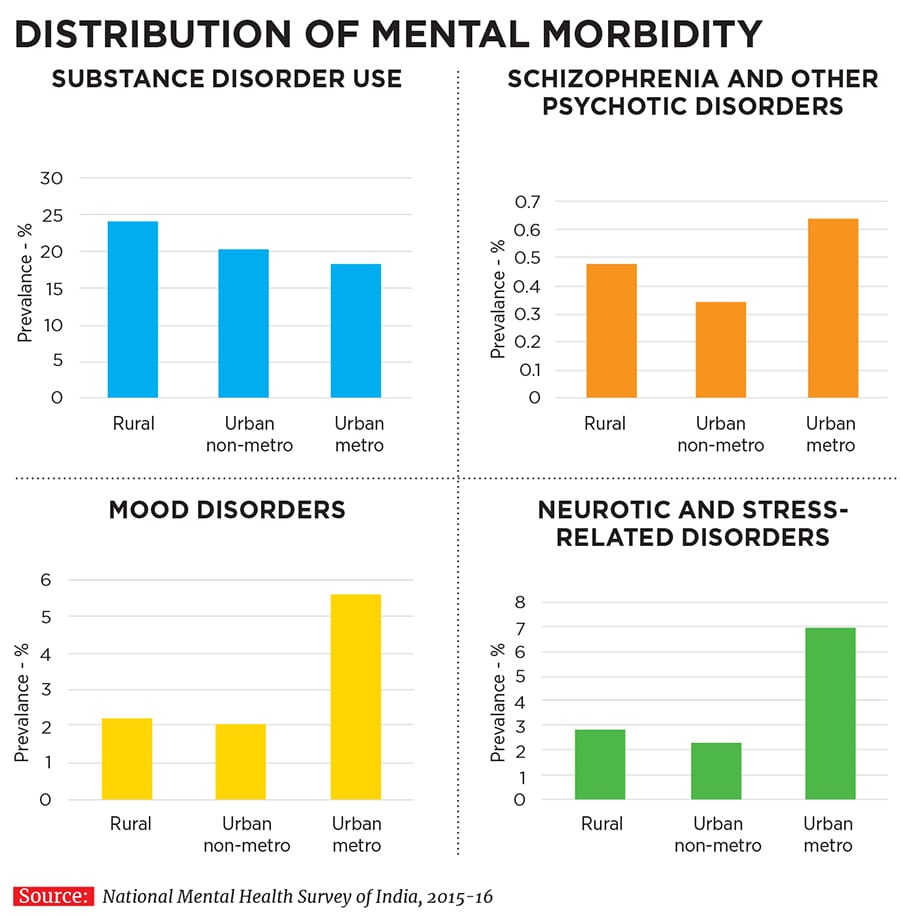

The National Alliance on Mental Illness describes mental illness as a medical condition that disrupts a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, ability to relate to others, and daily functioning. According to the National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16, mental illnesses and disorders are caused by a complex interaction of biological, social, cultural and economic reasons.

In India, besides the lack of understanding, there is a stigma attached to mental illness. That apart, there is a limited supply of trained professionals to treat people suffering from it. “People are more comfortable reaching out if there are emotional distress-related issues if it’s about mental illness, the stigma stops people from opening up and seeking help,” says Tanuja Babre, 26, programme coordinator of Tata Institute of Social Sciences’ (Tiss) iCall, a psychosocial helpline.

Ray of hope

Times, though, are changing. People are coming to terms with the seriousness of mental illnesses and acknowledging the need for help. “In 2014, when we were planning to start an initiative in the mental health care space, I wanted to call it the Mental Health Initiative. However, people told me it would be extremely negative. Today, there is more acceptance of the term, especially since celebrities like actor Deepika Padukone have spoken out about their battle with depression,” says Rajvi Mariwala, director, Mariwala Health Initiative (MHI).

While several organisations are at the forefront of this battle, a big ray of hope came in the form of the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017—passed by the Rajya Sabha in August 2016 and Lok Sabha in March 2017. It is the first time that India has passed a law that gives people the right to mental health care, an aspect neglected for years.

MHI is one of the few organisations in India that funds and strategically supports ventures and projects [in rural and urban areas] focusing on mental health care. “We look at innovative mental health projects that focus on human rights and are accessible to the marginalised communities. They need to raise awareness, have a good training component, deliver services effectively, have a robust referral system [to connect people to on-ground resources] and a research component,” adds Mariwala. To date, MHI has reached out to over 1.4 lakh people in India. Some of the projects it has tied-up with include iCall, Bapu Trust, Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy’s Atmiyata and Anjali.

Started in September 2012 and funded by MHI since April 2015, iCall has been working with the Maharashtra government on training programmes for the Mental Healthcare Act. “We are working with the state government to help with the implementation of the Act, but there are a lot of challenges. There is a dearth of trained experts in the country, so there is barely a team for us to train,” explains Babre.

Richa Singh (left) and Puneet Manuja (right), the co-founders of YourDOST in Bengaluru

Richa Singh (left) and Puneet Manuja (right), the co-founders of YourDOST in Bengaluru

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan

Tech boon

Usually, those suffering from mental illness prefer to remain anonymous while seeking help. Technology and a proliferation of startups tackling the subject help them do that. iCall, for instance, set up an email service a year after it was launched. It is now moving to the chat-based model. “Our aim was to ensure everyone has access to our services, without any geographical or financial restrictions. That is why our services are multi-lingual and for free,” says Babre.

Unlike other helplines, iCall claims it is run by professionals, not volunteers. As a result, 50-60 percent of the calls it receives are from follow-up clients. It even collaborates with the Maharashtra Police to conduct workshops for suicide prevention, given the stressed lives that members of the force lead. Babre concedes that helplines can’t be the only solution. “Face-to-face interactions are essential,” she says.

Like iCall, YOURDost is a sought-after helpline among young adults because of the privacy and personal interactions it offers via chats, voice and video calls. IIT-Guwahati graduate Richa Singh, 31, launched YOURDost in 2014 after a college friend of hers committed suicide. The online platform connects individuals with psychologists, life coaches and psychiatrists. “Contrary to popular belief, we find men seeking more support in matters like financial pressure and not being able to give time to their families. Around Valentine’s Day, they even talk about feeling lonely. During the exam season, it’s not just students, but also mothers who call for not being supportive enough to their children. More recently, we have had clients talking about their social media and internet addictions,” says Singh.

YOURDost has raised $400,000 in angel rounds from Phanindra Sama (redBus founder), Aprameya Radhakrishna (TaxiForSure founder), Aneesh Reddy (Capillary Technologies founder) and investors like Sanjay Anandaram (Seedfund), and Venk Krishnan (NuVentures). In 2016, it raised $1.2 million in a pre-series A round from SAIF Partners.

Among other startups that make optimum use of modern technology are InnerHour and TrustCircle. Founded by Amit Malik, 42, and Shefali Batra, 42, in February 2016, InnerHour provides online therapy and consultation it even offers face-to-face interactions when required. The Mumbai-based startup received an initial funding of $450,000 from Batlivala & Karani Securities India Pvt Ltd, investment firm Venture Works and others.

While a lot of players in the space focus only on online video/chat-based counselling, InnerHour has also developed a mobile application. “It asks a bunch of questions and then creates a 28-day programme with various 5-minute activities for the individual to work on each day. This is to help them develop emotional skills without seeing a therapist,” says Malik. The application also has features for immediate relief from any form of stress or anger. The founders are working on integrating artificial intelligence as part of the application. In extreme cases, InnerHour either asks the person to see its therapist or recommends one.

TrustCircle, on the other hand, was set up using the preventative, participatory and predictive (3P) model. Its focus was on improving emotional resilience, through its products, the flagship one being mHealth Tests. It is a mobile test that can be taken anonymously for free. “Most organisations are not focusing on preventative measures since they don’t realise their importance. If measures can be taken to prevent the illness at an initial stage, the individual might not need external help. Through the 3P model, we offer solutions that allow individuals to reflect, learn from and track their journey,” says Chaudhry.

Rural ramifications

Experts admit that there is a huge difference in the context and challenges related to the issue in urban and rural India. Organisations like the Schizophrenia Research Foundation (Scarf) and the Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy’s (CMHLP) Atmiyata Programme are trying to bridge the gap.

Scarf began experimenting with telepsychiatry in 2005 and received support from the Tata Trusts in 2010, when it moved its services to a mobile platform. The service is provided on a bus, which has a consultation room and a pharmacy. Through online video counselling, Scarf connects patients in remote areas to a psychiatrist based in Chennai. TrustCircle is a technology partner for Scarf and the foundation is now focusing on prevention and early intervention. “There is a standardised assessment that students in various schools and colleges have to take as part of an emotional wellness screening. This is to identify those who show signs of psychosis,” says Chaudhary.

While these mobile buses have gained popularity down south, the Atmiyata programme is focussed on Gujarat’s Mehsana district. It is co-funded by MHI and Grand Challenges Canada the latter funds innovators in low- and middle-income countries and in Canada. It follows the peer-to-peer training model where villagers are asked to volunteer to become ‘Atmiyata Champions’. “We train these champions to identify people who might have mental health distress, or as they refer to it, ‘stress and tension’. We teach them skills like problem solving and active listening so that they can help people with basic counselling,” says Soumitra Pathare, consultant psychiatrist and coordinator, CMHLP.

Amit Malik, who co-founded online therapy and consultation platform InnerHour

Amit Malik, who co-founded online therapy and consultation platform InnerHour

“On an average, there is a binary understanding of mental illness in rural India. At one level they understand what ‘madness’ means, but it is stigmatised on the other, they know what stress and tension mean, but those aren’t illnesses to them,” says Pathare. Nine months ago, CMHLP launched a suicide prevention programme in Mehsana called Spirit (suicide prevention and implementation research initiative) to bring down the number of suicides and attempted suicides.

Open mind

Mental health, unlike physical discomfort, is tougher to tackle, but experts feel technology and communication can bring about a positive change. “You could increase awareness, which would tackle stigma and then offer people products and services that are easily available, using which they could get better,” says Malik of InnerHour. New laws like the Metal Healthcare Act and a growing conversation on the subject augur well, but there’s still a lot left to be done. “We would love to see a mental health ecosystem coming together with a social environment that is accepting of persons with disabilities [both mental and physical] and has enough people willing to fund mental health. Our aim is to work collaboratively with others, and change the conversation surrounding mental health in India,” says Mariwala.

First Published: Sep 20, 2018, 11:30

Subscribe Now