Stuck in commuter hell? You can still be productive

Commuters who listen to music or browse social media might be increasing their chance of a stressful workday. Research by Francesca Gino and colleagues offers better ways to cope with a bad commute

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

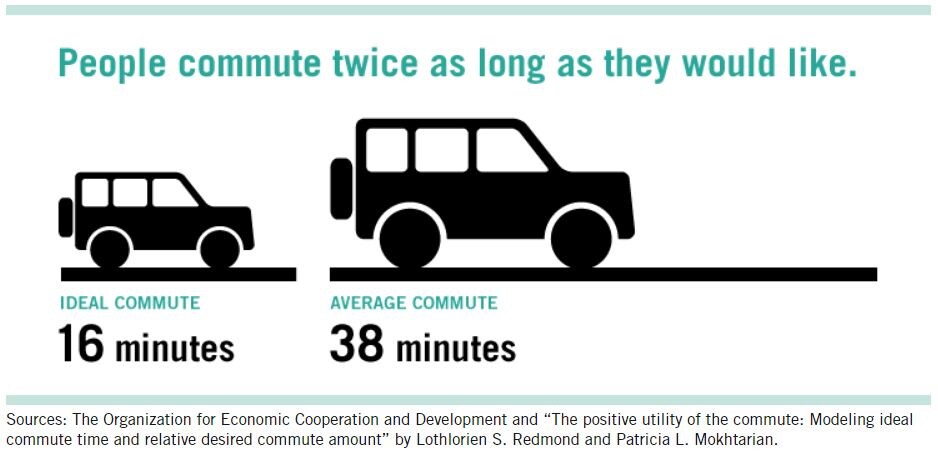

Workers commute an average 38 minutes each way between home and work—a trip that can feel like a dreadful chore before the workday even begins. In fact, long commutes lower job satisfaction and increase employee turnover.

Now, recent research provides some advice to ease the pain of the commute: Employees should think about work on the way to work by mentally mapping out a plan for their day.

By using the travel time as an opportunity to get into the work mindset, employees are giving themselves a chance to make an easier mental shift from their home role to their work role, and ultimately, this makes people feel happier about their jobs, according to the working paper Between Home and Work: Commuting as an Opportunity for Role Transitions.

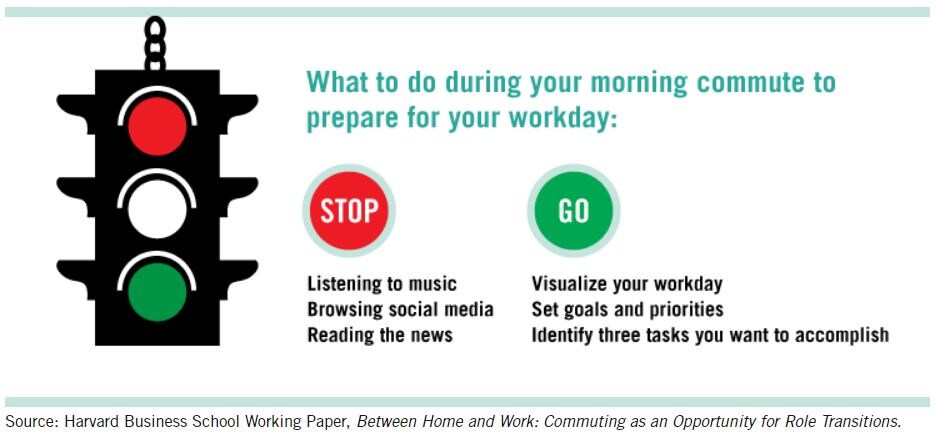

Meanwhile, doing relaxing or purely pleasurable things on the way to the office, like listening to music in the car or scrolling through social media on the train, may actually interfere with people’s ability to transition into work mode smoothly—which makes them feel gloomier about their jobs and more likely to quit.

“I was surprised with this finding myself,” Harvard Business School Professor Francesca Gino says. “The idea that we need to work to transition from our home role to our work role is not always intuitive. One would think that switching roles is as easy as putting on a different hat. It turns out that transitioning between roles takes time and effort, and it’s a part of the day we need to pay more attention to.”

Gino, the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration, coauthored the paper with Jon M. Jachimowicz of Columbia Business School Julia J. Lee of the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan Bradley R. Staats of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Jochen I. Menges of the University of Zurich.

Workers with long commutes dislike their jobs more

Previous research shows the longer people commute, the lower their job satisfaction and the more likely they are to quit. In one 2006 survey, people said that the morning journey between house and office was their least desirable activity of the day.

Many workers endure much lengthier commutes than the 76-minute roundtrip average in fact, commutes are getting longer in general. One study found that the distance between employees’ homes and workplaces in the United States increased by about 5 percent between 2000 and 2012.

Commutes are stressful partly because people are unsure how long the trip will take, and if bad traffic makes them late for meetings, they start the workday feeling rushed and on edge.

“You can’t adapt to commuting because it’s entirely unpredictable,” psychologist Daniel Gilbert says in the working paper. “Driving in traffic is a different kind of hell every day.”

Gino and her colleagues set out to look at why commuting rubs us the wrong way, who is most affected by traveling long distances to work, and how people can better cope with the trip. They found that during a lengthy commute, employees are in limbo between their home and work roles. This unstructured time gives rise to “role ambiguity,” leaving people with the unpleasant feeling of being unsure what they’re expected to do.Yet, although people say they dislike commuting, when asked about the “ideal” commute length, workers don’t say “zero.” One study finds the optimal commuting time to be 16 minutes.

Some workers struggle with commuting more than others

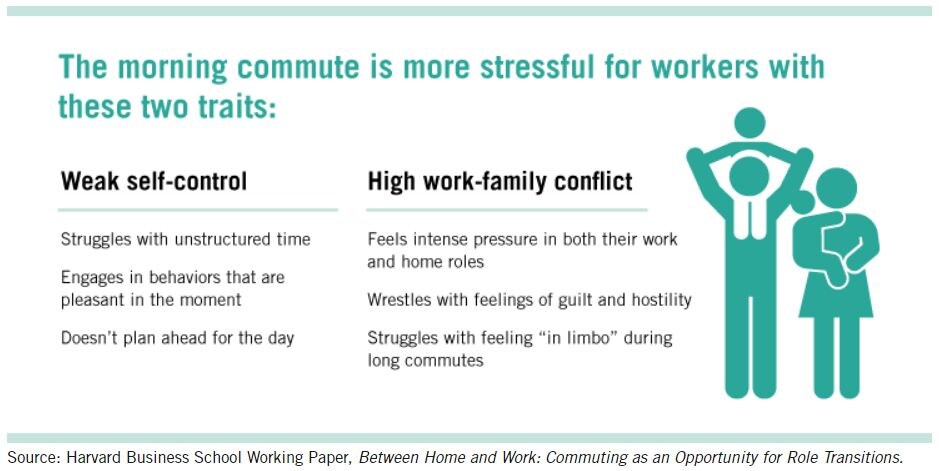

As it turns out, just how stressful a commute feels depends on who you ask, with some workers feeling more bothered by long commutes than others. The results of three studies by Gino and her team show that the morning commute is harder on certain types of people:

People with lower “trait self-control": Workers with high levels of trait self-control have a keen ability to regulate their behavior, thoughts, and emotions. These employees set goals for themselves, keep focused, and stay on track with their goals. The researchers say employees with high trait self-control tend to take commuting more in stride, since they naturally transition into their work role more easily by setting priorities for the day ahead.

Meanwhile, workers with lower levels of trait self-control don’t plan ahead as much and are more likely to engage in thoughts and behaviors that are rewarding in the moment, like listening to music or daydreaming. But these relaxing activities during the commute can actually hinder their ability to seamlessly transition into their work role. Worse, if people arrive at the office with lingering thoughts about their home role, that often frustrates entry into their work role, leaving them more vulnerable to the strain of commuting, less satisfied with their jobs, and more likely to quit.

In one survey of employees at a UK media firm, the research team found that for every 15-minute increase in commuting time, the job satisfaction of employees with weak trait self-control dropped by .26 points on a one-to-seven point scale. These unhappier workers were also more likely to subsequently quit their jobs, whereas people with high trait self-control were not affected by lengthier commutes.People with high levels of “work-family conflict": Workers often feel intense pressure from both their home and work roles, with the two roles seeming incompatible at times. Employees may have trouble, for example, finding a comfortable balance between juggling the needs of their young children along with the requests of a demanding boss.

This conflict in roles can lead to burnout, guilt, and hostility both at work and at home—and, in the extreme, even poor health among working adults. Employees with greater work-family conflict have a tougher time transitioning to their work roles, and as a result, a long commute takes a bigger toll on these workers.

Gino and her colleagues found that the employees who wrestle the most with commuting also benefit the most from the mental transition strategy they recommend called “role-clarifying prospection”—thoughts about the tasks they’d like to accomplish during their upcoming role at work.

In one study, the researchers conducted a four-week-long field experiment in which 443 participants commuted about 52 minutes on average, with 85 percent of them traveling by car. The researchers gave some commuters a prompt that said: “Please use your commuting time to focus on your goals and make plans about what to do (during your workday).” Other commuters were encouraged to do something they enjoyed in the moment: “You could listen to music, read the news, or catch up on social media—anything that you inherently enjoy is fine.”

The commuters who made plans for their workday reported significantly higher levels of job satisfaction and reduced intentions of leaving their jobs than those who did something enjoyable in the moment.The strategy shifts people’s attention from what is happening in the present—the not-so-fun commute—to thoughts that give them a head start with work. This “future focus” adds some structure to what is typically unstructured time and allows people to feel prepared for the day ahead. (It’s effective in the same way other rituals, like exercising before work, can help people transition between their home and job roles, the researchers say.)

Business leaders can help workers manage commuting

The research suggests that this “role-clarifying prospection” strategy may also work in reverse, so people should avoid ruminating about work-related problems during the drive home. Letting work go during the evening commute by thinking about what to make for dinner or what activities to enjoy with the children will likely help people transition to their home roles more easily.

Although the strategy helped commuters during the four-week study, it’s unclear whether it would have lasting effects in the long term, the researchers acknowledge. But the team points out that if the strategy becomes a habit, it might not take much effort to train ourselves to engage in thoughts during the commute that prepare us for the role ahead.

Knowing that a long commute can make or break the job for some workers, the research team hopes business leaders will talk to their employees about how to handle the distance—which just might allow companies to retain more workers.

“Leaders can help their employees understand that a commute is something that needs to be managed,” Jachimowicz says. “In addition, understanding that longer commutes can be difficult for employees is important for organizations, who may want to promote greater flexibility in work arrangements, such as working remotely.”

The team also wants employees to know they might be happier with their jobs overall if they can shift from thinking about themselves as “passive actors” during the commute to viewing that time as a potentially productive period.

Lee used to arrive at work exhausted after commuting as much as 100 minutes. “Every morning was a hell with lots of traffic and angry drivers,” she says. She now travels fewer than 10 minutes, yet even workers with a short drive may benefit from using that time to plan what they intend to accomplish when they arrive: “Think about the three most important goals or tasks that they need to achieve during that day,” Lee advises.

First Published: Apr 03, 2019, 12:19

Subscribe Now