Travel: New Zealand's Doubtful Sound holds a unique marine habitat

Doubtful Sound is the second longest of the 14 fjords in New Zealand's Fiordland region, created millions of years ago

Doubtful Sound is the second longest of the 14 fjords in New Zealand’s Fiordland region

Doubtful Sound is the second longest of the 14 fjords in New Zealand’s Fiordland region

Image: Thomas Lusth/ShutterstockIn 1770, when British navigator Captain James Cook sailed the Endeavour on his first expedition to New Zealand, he came upon its southwest coastline, fragmented by water channels that extended like long, slender tentacles into the land. As he contemplated entering a narrow inlet of water just south of Secretary Island, he wrote in his journal: ‘A little before noon we passed a small opening in the land where there appeared to be a very snug harbour formed by an island lying in the middle of the opening. The land on each side of the entrance of this harbour riseth almost perpendicular from the sea to a very considerable height.’ Cook doubted whether the westerly winds would allow him to sail back out, and so he left the channel unexplored, naming it Doubtful Harbour.

Cook is a central figure in New Zealand’s history, credited with the first European mapping of the country. Like the country’s tallest mountain, Mount Cook, many of its points of interest are named after, or by, the early explorer.

Doubtful Harbour was renamed Doubtful Sound in the early 1800s, when sealers and whalers frequented the 40 km-long water inlet. Somewhat confusingly, Doubtful Sound is not actually a ‘sound’—a geographical feature formed when rising seas flood a river valley—but a fjord created millions of years ago. In the Ice Age, massive glaciers chiselled the landscape to form deep valleys and rifts in the mountains. As the glaciers retreated, the sea rushed in to flood the valley that remained, leading to the creation of the fjord.

Doubtful Sound is the second longest of the 14 fjords in New Zealand’s Fiordland region, and since the days of Cook’s Endeavour, several vessels have charted a course along it. On an overnight cruise aboard the three-masted Fiordland Navigator, I chart the same course, sailing between mountains of granite even as slim flute-shaped clouds hang low beneath the mountaintops. These are the very clouds New Zealand is named after. Aotearoa, the Maori name for the country, translates to ‘the land of the long white cloud’, and a map of New Zealand bears a striking resemblance to the formations I see.

As the ship sails out towards open water, the Tasman Sea greets us with great swells, dousing everyone on the lower deck. I stand at the bow of the upper deck, with a sweeping, 180-degree vista of the watery wilderness. A solitary albatross glides ahead, slender, dark wings unruffled, even as our vessel rises, rocks, and falls in the waves. Icy winds gather force as they rush across the Tasman Sea and funnel through the fjords in sharp blasts. Captain Dave Allen ensures we stay out on deck with a simple announcement: “Fur seals, up ahead”.

*****

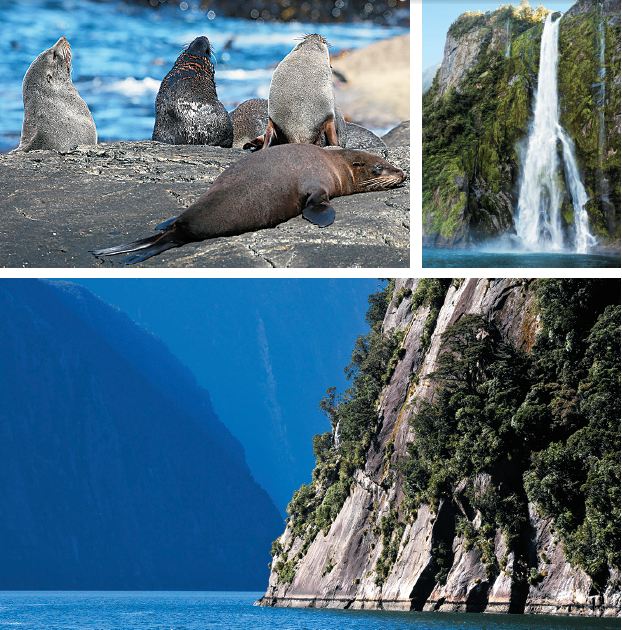

At the mouth of Doubtful Sound, where it opens into the Tasman, the Nee Islets are a jagged, rocky outcrop iridescent in the fading sunlight. As my eyes adjust to the light, I spot the silhouettes of small, wobbling creatures on the rocks. Like blobs of jelly, the New Zealand fur seals drag themselves across the rocks to eventually flop down on sunlit patches.

In the 1800s, these fur seals were hunted close to extinction for their blubber and skin. It was only in 1946 that they gained protection, when their hunt was banned in New Zealand. Today, there are over 200,000 New Zealand fur seals across the country.

As the Navigator retreats from the sea back into the calm waters of the fjord, Captain Dave and on-board naturalist Kelvin Wilson keep up a constant dialogue on the landscape that surrounds us. We sail between mountains of granite, dark slate, and limestone, dressed in forests of silver beech trees. In the absence of a topsoil layer, the trees lock their roots and cling to the rock face. Fiordland receives around 7 m of rain in a year, and with no proper support, the forests are periodically washed down the mountainside. We pass walls of bare rock riddled with deep gashes, where an avalanche of trees has left the cliffs naked. The forest regenerates itself every 90 to 100 years, sustaining on a diet of nutrients from lichen and moss.

Dave describes Doubtful Sound’s unusually dark waters as “a cup of tea without milk”. Rainwater runoff brings with it tannins and stains from the forest, and settles atop the heavier seawater, resulting in a nearly opaque fresh water-saltwater sandwich.

It is when we get off the ship, and into solo kayaks, that I get a real close-up view of New Zealand’s spectacular landscapes. In the shadow of sheer cliffs, I navigate a 2-km stretch along the icy black waters of Doubtful Sound. The dark top layer of water blocks out the light and tricks deep-sea species into thriving just 10 m below the surface. At its deepest, Doubtful Sound is around 400 m, but all marine life exists only in the top 40 m. Beneath that is only darkness.  With rainforests, waterfalls, and marine wildlife, Doubtful Sound is a true water wilderness

With rainforests, waterfalls, and marine wildlife, Doubtful Sound is a true water wilderness

Image: ShutterstockWith rainforests and waterfalls, seals, dolphins and penguins, Doubtful Sound is a true water wilderness. Over the course of two days, I had seen dazzling blue sunlit skies and honey-coloured sunsets, and now, an ominous forest loomed ahead of my kayak. Rowing close to the rock face, I see curling green tendrils of moss hang above the water’s edge. The only sounds are that of my paddle hitting the water, and the distant rush of a waterfall.

For the duration of the cruise, there is no other vessel or human activity in sight along the inlet. While nearby Milford Sound, also in Fiordland, is among New Zealand’s most popular tourist spots, Doubtful Sound remains quiet because of its remote location and no direct road access.

To get here, I’ve had to take a bus from Queenstown to Manapouri to board a catamaran across Manapouri Lake, which sails past the Southern Alps to deposit us on the lake’s western bank, where the Manapouri Power Station is located. This is the country’s largest hydroelectric power station. From there, another bus ferried me across a 21-km mountain road that was built to aid the construction of the power plant. New Zealand’s most expensive road winds past the 2,100 feet-high Wilmot Pass to Deep Cove, where our cruise finally began.

Isolation and conservation efforts go hand in hand in protecting the ecology of this Unesco World Heritage site. On my second morning aboard the ship, as we cruise down Hall Arm, Captain Dave gets our attention once again when he turns off the engines. “Dolphins!” he says. Metres ahead of us, a handful of adult and baby common bottlenose dolphins put on a show as they leap in and out of the water. Glistening silver in the sunlight, they swim very fast, coming up to the ship’s edge and vanishing into the depths of the water. “There is a pod of around 69 dolphins that live in this stretch,” says Wilson. “Doubtful Sound is home to one of the southernmost populations of these dolphins. They have adapted by growing larger in size to combat the cold water temperatures.”

To protect these creatures, the Department of Conservation has defined Dolphin Protection Zones where vessels are not permitted to cruise. Motorised vessels are not allowed within 200 m of the shore, and there are limits on the number of commercial ships that can ply the fjord. Similar checks are in place for other species that inhabit these parts. Guidelines also specify that all marine life encounters should be left up to chance.

The playful dolphins stay with our ship all along Hall Arm, gliding in the shadow of the vessel’s bow. From my spot on the deck I can clearly see their blowholes, and their slender snouts look like they are stretched into smiles.

As we approach the narrow end of Hall Arm, where the cliffs appear to close in on us, Captain Dave turns off the ship’s engines and for the first time, the generators as well. As the thrum of machinery dies away, he has a request for everyone on board. “Grab a spot, put your phones away, and save your conversation for a little later please,” he asks of us. Footsteps on the steel decks stall, the click-click of phones pauses, and voices dissipate. For the next 10 minutes, the noises of the everyday world we live in are replaced by the faraway sounds of nature: The distant whoosh of a thread-thin waterfall gushing down the rock face the piercing tweet of a bird from deep within the bush the soft plop of fine rain hitting the water’s surface. For the first time in a long while, I tune in completely to the sounds of silence.

First Published: Oct 05, 2019, 08:49

Subscribe Now