Travel: By the Mekong in Laos

The Mekong in Laos is central to the lives of people along its banks, and presents a gamut of experiences to visitors as well

Of the Mekong’s total length, nearly 1,900 km flows through Laos it is known as the Sea of Laos

Of the Mekong’s total length, nearly 1,900 km flows through Laos it is known as the Sea of Laos

Image: Anita Rao KashiIt is just past dawn on a July day, but a muted buzz fills the air. From the road, at regular intervals, long flights of steps lead downwards, with people going up and down in a controlled rush, ferrying things. But none of the frenzy is reflected in the river that flows gently by, unperturbed and tranquil. The Mekong in Luang Prabang, Laos’s cultural heart, seems untouched by everything that goes on around it.

Landlocked as Laos is, the Mekong is central to the Laotian scheme of things everything substantial seems to be somehow associated with it. The 4,350 km-long Mekong originates in China’s Qinghai province and flows through Tibet, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam before draining into the South China Sea. In its upper reaches, it flows through deep gorges, rugged landscape and inaccessible terrain until it reaches the border between Myanmar and Laos. Subsequently, it flows through plateaus and plains through Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Of the river’s total length, nearly 1,900 km flows through Laos, and is also known as the Sea of Laos.

Looking down at the river from my vantage point on Khem Khong Road, I am overtaken by the urge to jump into a long wooden boat for a ride, and discover the treasures of the river.A boat ride gives a glimpse into the hamlets and villages along the banks of the Mekong

I did not have far to go. Diagonally opposite from where I boarded is the Wat Long Khoun, a Buddhist temple complex built in stages by the royal family between the 16th and early 20th centuries. It is a simple white structure topped by a pagoda, which stands on nearly four acres surrounded by lush green trees. Inside are fading murals from the Jataka Tales, but more eye-catching are the colourful drawings of bearded Chinese guards flanking the main gilded door. Around the temple are six wooden huts on concrete pillars that serve as living quarters of monks, as well as a few other structures such as the meditation room, dining room and kitchen.A sense of deep calm surrounds the temple, broken only by the calls of birds and the occasional muted whirr of a boat plying by. There are fleeting glimpses of the monks, and from inside one of the huts rises the sound of chanted prayers. “This was an important temple till Laos had a monarchy. The king-designate spent three days in meditation and ritual bathing in the river before crossing the river for his coronation,” Phaeng, my guide, says.

Buddhism, which came to Laos in the 7th century from Thailand, always enjoyed royal patronage. Although both Theravada and Mahayana forms of the religion were introduced in the country, it is the former which is practiced, with about 65 percent of the population being Buddhist. It continued to thrive over the centuries, through French colonial times of the early 20th century and Communist rule later.

A few hundred metres from Wat Long Khoun is the village of Ban Xieng Maen, populated with wooden houses, noodle shops, the frequent sputtering of two-wheelers and people hauling in the day’s catch, household supplies and even drinking water from long colourful wooden boats moored at the edge of the water.

Almost directly across the river from Wat Long Khoun is Wat Xieng Thong, the religious symbol of Luang Prabang, where kings were crowned till 1975. The mid-16th century temple, also called the monastery of the golden city, was once the gateway to the town. In contrast to Wat Long Khoun, this complex is sprawling with nearly two dozen structures scattered across a vast compound, with the main temple displaying rich and luxurious interiors, exquisite mosaics and gilded details. It is also busy, with visitors and monks wandering around the complex.

For thousands of years, the Mekong has been an essential part of Laotian life, inextricably weaving together sustenance, livelihood, industries, spirituality and politics. Over 70 percent of the country’s 7.2 million people are estimated to live in the Mekong basin. The river supplies water for consumption and agriculture, with nearly 90 percent of vegetables and almost all coffee being grown in its basin almost 25 percent of global freshwater fishing is from the Mekong. The Pak Ou caves have several Buddha statuesAs the sun rises in the sky, Wat Xieng Thong gets crowded with the arrival of a busload of tourists, and I get back on the river for a 20-minute ride downstream to Laos’s and Luang Prabang’s latest and most ambitious project, the Pha Tad Ke Botanical Garden. Spread out on 40 hectares of tropical forest land—about 14 hectares is landscaped into gardens, while the rest is natural vegetation—against limestone cliffs and a steep hill, the only way it can be reached is by the river.

The Pak Ou caves have several Buddha statuesAs the sun rises in the sky, Wat Xieng Thong gets crowded with the arrival of a busload of tourists, and I get back on the river for a 20-minute ride downstream to Laos’s and Luang Prabang’s latest and most ambitious project, the Pha Tad Ke Botanical Garden. Spread out on 40 hectares of tropical forest land—about 14 hectares is landscaped into gardens, while the rest is natural vegetation—against limestone cliffs and a steep hill, the only way it can be reached is by the river.

The steps leading up from the river’s edge provide stunning views of the Mekong. At the top, the path opens into a beautiful garden stretching out under a thick canopy of greenery. The garden is established on the former hunting grounds of the royal family and consists of an arboretum, a ginger garden, a bamboo garden, an orchid nursery, water bodies and other elements. It was opened to the public in 2016 and is home to more than 1,500 species of plants.

It also includes a limestone habitat and a cave. But the most compelling part is the 3,000 sq mt ethno-botanic garden with 10 themed plots showcasing Laos’s rich plant diversity and local knowledge of medicinal plants. It includes medicinal plants for people and elephants, poisonous plants, plants for textile making and even plants for spirits.

From here, armed with a smattering of English words and a profusion of hand gestures, the boatman indicates the next stop is an hour away, even as he waves and shouts out greetings to passing boats and canoes. As my boat gathers speed, a steady breeze carries with it the river’s smells. We pass hamlets and substantial villages along its banks: People wash clothes and vehicles in the river’s water, children jump and splash around in it, motorised boats (like mine) and row boats ply up and down with merchandise, while three-plank fishing canoes opt for a more sedate pace. Where there is no human habitation, there is an abundance of green plains with paddy fields, gentle hills and steep mountains.

Amid the chaos that sometimes surrounds the river is an isolated island that makes the waters fork around it. At first glance, it appears deserted, but as we near the banks, I see a handful of young monks bathing and washing their robes, their bright saffron colours standing out against the green of the water and blue of the sky. The island is home to Wat Donekhoun, or Island Temple—a simple structure done in ochre and red with a tiled roof, which houses a towering Buddha statue—and half a dozen monks. Every morning, they cross the Mekong to surrounding villages for alms and subsist on the day’s collections.

A few minutes from the island of tranquillity is the village of Ban Xang Hai, where a set of steep steps from the river bank leads to an open shed that is the whiskey production facility of Mr Somboun. Called ‘Lao-Lao’ or ‘whiskey’ village, Ban Xang Hai is popular for the whiskey and rice wine it produces in a rustic set-up. In broken English, Somboun explains the process and attributes the distinct taste of the brew to the various nutrients in the waters of the Mekong.

At 50 percent potency, the whiskey is sharp and intoxicating, while the wine is sweet and equally potent both are made from local ingredients. For instance, the wine is made from sticky rice, and is fermented and distilled over four weeks. They are sold commercially all over the country. However, more startling are the multiple rows of bottles filled with golden brown whiskey in which are immersed snakes, scorpions and other kinds of reptiles the creatures are supposed to enhance the flavour of the brew, and act as aphrodisiacs. Samboun suggests I try one of the ‘snake whiskies’, but I, filled with horror, refuse.Lao-Lao is popular for its whiskey and rice wine. Some bottles have snakes and scorpions in them

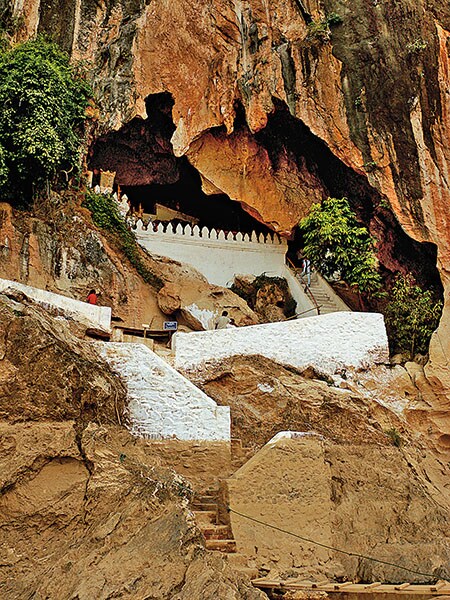

A short distance from Ban Xang Hai is one of Mekong’s most spectacular sights. At the juncture where Nam Ou river, which originates in North Laos, meets the Mekong, a set of karst mountains rises dramatically from the river. Their face is craggy, with steep steps leading up from the water’s edge to caves, lower and upper, and collectively called Pak Ou. Inside the lower cave, which is a series of caverns, sits a profusion of Buddha statues in various sizes, shapes, materials and poses some even dressed in golden robes. Looking out from inside the cave, the statues are gloriously silhouetted against the beautiful riverine scenery outside.In one corner, a handful of women sell flowers and other offerings for the devout. And despite the constant ebb and flow of people, the cave is quiet and tranquil.

A 10-minute climb from here leads to the upper cave, perched about 50 mt above, with its entrance surrounded by trees. Inside are more Buddha statues. Together, the two caves house between 4,000 and 6,000 of them. But there’s one thing in common: All of them have some imperfection, and are most likely broken or chipped. Rather than discarding the broken idol, Loatians have been depositing them in the caves, as a kind of final resting place.

Back on the Mekong, the long ride back to Luang Prabang seems surprisingly quick, but provides a window to contemplate the many facets of the river, and the ways in which it is intertwined with the lives of the people along its banks. It only seems apt that the English word Mekong is a shortened form of the Laotian Mae Nam Khong, meaning ‘mother of waters’.

First Published: Nov 02, 2019, 10:30

Subscribe Now