There isn't, and there needn't be, such a thing as "Indian photography": Nathani

Nathaniel Gaskell talks about the first book to document the history of photography in the country, and its significance to art history

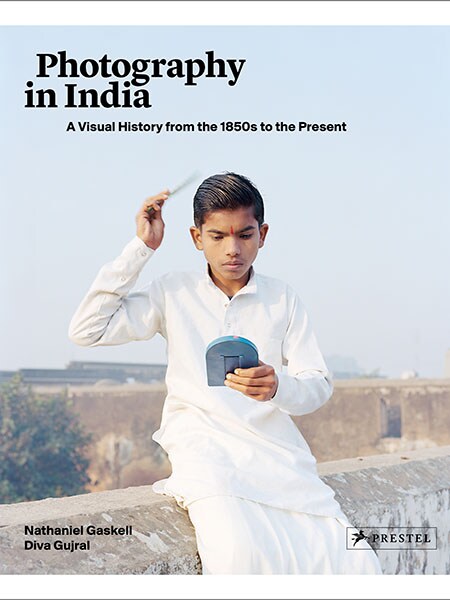

Photographs courtesy: Photography in India: A visual history from the 1850s to the present

Photographs courtesy: Photography in India: A visual history from the 1850s to the present

Nathaniel Gaskell, co-founder and associate director of the Museum of Art & Photography in Bengaluru and Diva Gujral, PhD scholar at the department of History of Art, University College, London have co-authored Photography in India: A Visual History from the 1850s to the Present, the first in-depth survey of the remarkable story of photography in India.

Covering 150 years and more than 100 Indian and international photographers, the book contains a wealth of previously unpublished material and lesser-known artistes. In a conversation with Forbes India, Gaskell (33) talks about the various complexities related to photography in India, and the challenges of distilling them into a book. Edited excerpts:

Q. It is surprising that there’s been no book that surveys the entire history of photography in India until now.

There’ve been several very good scholarly books on 19th century photography that focus on singular collections. Then, there have been about two or three books on contemporary photography in India, and of course, many fantastic monographs on individual photographers, but there hadn"t yet been a book that objectively looks at the entire history of photography in India from the beginning until now. We thought that needed to be done because it is so interesting to see things not in isolation, but how photographers were representing the country and responding to it 170 years ago versus how they are today.

Q. Had you thought of this book when you began as a curator with Bengaluru-based photo agency and archive, Tasveer?

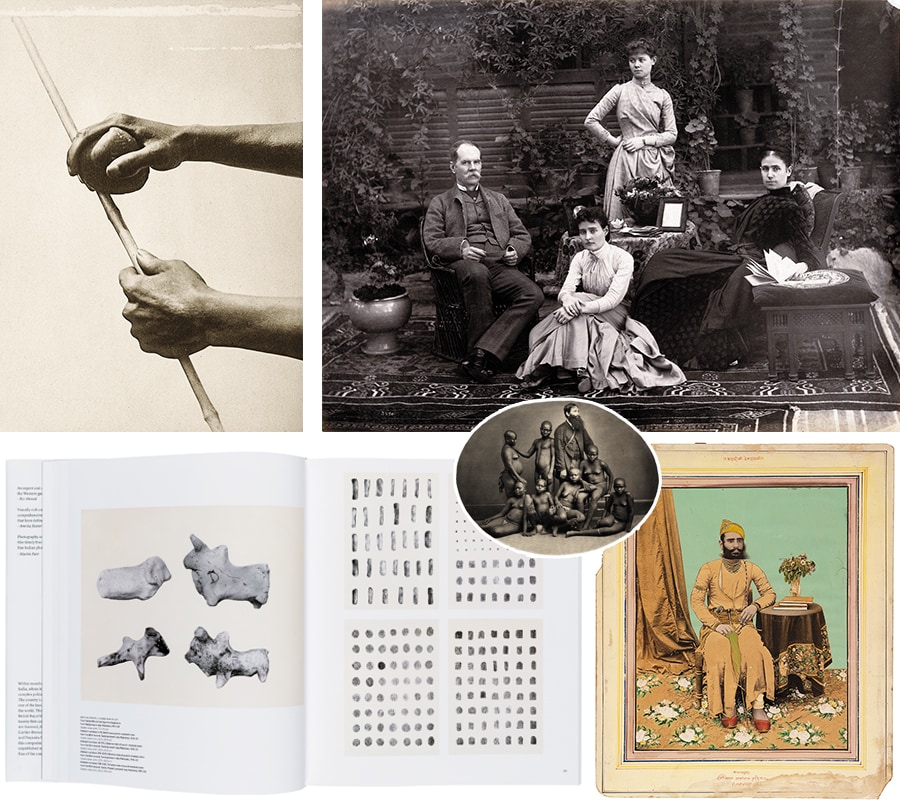

I began thinking about this book a few years after joining Tasveer in 2010. But I’m glad I didn"t work on it then as I don"t think I would have been equipped to do so. I hadn’t been researching photography in this country for nearly long enough. It has taken years of research and trying to understand photography here to feel that we can do even a half decent job representing this history in a book. It took two years to define its framework alone. I met Diva Gujral in 2016 and discussed the idea for the book and asked if she wanted to collaborate on it because we both brought different views to the table, and it was important that the decisions we made were subject to long discussions, not only about who to include, but where to include them in the larger narrative. Since then, we worked on the book together and she"s been integral to forming some of the arguments and ideas contained within it. (Clockwise from top left) Maurice Vidal Portman: Studies from the Andaman Islands, 1890 Lala Deen Dayal Ghasiram Haradev Sharma: Bhadariji Devarajaji, 1890 Saché & Westfield: Andamanese group with their keeper Mr Homfray, 1865 John Marshall: Four terracotta animal figurine fragments (1913–33) from Nal in Pakistan punch-marked coins (1913-33) from the Bhir mound in Pakistan’s Taxila

(Clockwise from top left) Maurice Vidal Portman: Studies from the Andaman Islands, 1890 Lala Deen Dayal Ghasiram Haradev Sharma: Bhadariji Devarajaji, 1890 Saché & Westfield: Andamanese group with their keeper Mr Homfray, 1865 John Marshall: Four terracotta animal figurine fragments (1913–33) from Nal in Pakistan punch-marked coins (1913-33) from the Bhir mound in Pakistan’s Taxila

Q. Had you worked with Indian photography before you came to India in 2010?

As a masters student at The London Consortium, I had been working with mid-20th century American photography. My research at the London Consortium had to do with conceptual photography in the 1950s and ’70s America. Later, I started working for the photography dealer Eric Frank. Eric, who was Henri Cartier Bresson’s brother-in-law, had a huge collection of mid-20th century European photography and Bresson’s work. Bresson had photographed in India a lot in the 1940s and ’50s. In a way, his work was my first introduction to photography in India.

Eric also represented Karen Knorr who had just begun her work in India. Karen told me of the exhibition Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 years of Photography from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh at the Whitechapel gallery in London in 2010. I went for the show, saw that one of the major lenders was the collector Abhishek Poddar, got his number and called him up on the same day, and he invited me to India. That’s how it all began… and a few years later I became the director of his gallery Tasveer, in Bengaluru.

Q. There were hardly any galleries engaging with Indian photography then.

The work I wanted to do was not just about building an archive or working with collectors in India, but positioning the work of Indian photographers in foreign collections. Traditionally, the big museums in the West acquired a lot of 19th century work because of what was “collected” from former colonies, but very little of photography from elsewhere or other time periods. When it comes to 20th century and contemporary art from South Asia, especially photography, their collections are pretty non-existent. This motivated me to build these collections whilst at Tasveer and try to get institutions in the West to start looking more at Indian photography. It was a long and slow process, and of course whilst there were few galleries doing this, we were not alone, and should acknowledge the great work of Sepia Eye in New York and PhotoInk in Delhi.

If you look at the academic courses or any book on the history of photography itself, it’s all European and American, there won’t be a single Indian photographer featured in them. That’s because academics, while researching, look into European and American institutions’ collections and American and European photography is all they find. Obviously, the history is going to be written from those finds.

So, this is what I wanted to do with my career here in India: To begin at least by putting some work from this part of the world in those collections, so that researchers of photographic history in the future will include a more global perspective. I’m now working on a more comprehensive plan with my role at the Museum of Art and Photography that’s coming up in Bengaluru, where a key part of our mission is to lend the photographic holdings we have to institutions outside India, again with this idea of building up institutional awareness in South Asian photography abroad.

Q. This process of weighing in with the institutions abroad is a complex one.

It’s taken many years, travelling abroad and engaging with curators from foreign institutions, familiarising them with the work of Indian photography. Again, this is not just a solo effort of the museum or Tasveer, and organisations such as Alkazi and the aforementioned Sepia Eye and PhotoINK have all made huge contributions to this work. While at Tasveer, I learnt and perhaps even made mistakes, as a young gallery and with me as a young director, working things out as we went. In fact, it is now, after all of that work done over the years—being the first Indian gallery at both Paris Photo and Aipad, the two main international art fairs for photography for over five years—that serious collectors have begun to buy work by Indian photographers, and finally the scene is really happening. A lot of museums in the West are waking up to these gaps in their collections and are starting to collect photography. It’s exciting to see. Finally, the Western bias in the art world is shifting and I think the whole way in which art history in the future will be looked at will be much more expansive. Q. Well, photography is a recent invention and it coincided with colonisation in the 1860s. You did mention in your introduction that not all photographic exercises during the colonial period were necessarily an expression of the Imperial mindset. Can you elaborate?

Q. Well, photography is a recent invention and it coincided with colonisation in the 1860s. You did mention in your introduction that not all photographic exercises during the colonial period were necessarily an expression of the Imperial mindset. Can you elaborate?

From an academic point of view, it’s easy to look through early photography retrospectively and declare that all these photos are a sign of an imperial agenda, though some were, and especially in the pseudoscience of physiognomy in ethnographic photography of tribes etc. These photographers themselves may have been a product of their times, but it isn’t that they were thinking about how they could further the agenda of the Empire through the pictures they were making.

You do get photographs that toe the colonial line, which are problematic to deal with, but there are also photographs of archaeological studies that operate outside a colonial agenda, and are beautiful artworks in their own right. One looks at some works as an expression of fascination—by someone from a different part of the world—with a medium that had just been invented. Of course, the work documenting tribes and races is deeply problematic, which is definitely a combination of colonial agenda—to show the colonisers as superior, and the colonised as inferior. This sort of work is uncomfortable to look at today but all of the work wasn"t like that.

Q. When researching for a photo story on tribes, I realised what a thin line it is… take for example, photos around female genital mutilation among the tribes of Africa. Because it was seen as abhorrent practice, the world’s attention remained focussed on the social issue, otherwise it could easily have been seen as another example of exoticisation by a ‘Western’ photographer.

That’s interesting, because the photographic work that is more problematic is 20th century photo-journalism—the Magnum Photos generation and Steve McCurry’s work in India—painting the country in an exotic way, which is wrong. When the first wave of photographers in the late 1800s were here, they may have been representative of a particular mindset, but they were photographing Indians to document them as part of what was seen as a wide ethnographic project. Today, you can say that it is very problematic but they were reflecting a country that had this mindset, of Victorians who liked to categorise, photograph and keep people in a book. But it is photographers like Steve McCurry, who, knowingly—and when the world knows that objectification of the past is problematic—painted India as if it were still stuck in rural 19th century, consciously making it as a timeless, exotic kind of country, which, by then, it wasn’t. That’s perhaps more problematic than what the 19th century colonial photographers were doing.

Q. But then, Steve McCurry’s work may have been the result of a demand made on him by a magazine like the National Geographic. We’ve seen it first hand when a documentary photographer is assigned for a travel story, and the results show a certain degree of prettifying to appeal to the travel reader.

This idea of a timeless India sells. That’s why our book features a whole chapter criticising Western notions of exoticism, like an early fashion shoot in India by the photographer Norman Parkinson, as we wanted to clearly call out his part of the history of photography in India. It clearly spells out its commercial intent, saying ‘we want to paint India in a certain way against an exotic backdrop and it sells magazines’. It’s not only that though. When McCurry is making books for himself, he is—in some cases we know atleast—still literally editing out any signs of modernity or progress that shows up in his photos, which I personally think is wrong, ethically, although we try and keep a balanced perspective in the book and just communicate the facts. Q. How did you go about clarifying India’s scale, diversity and multitude of realities, from over a century, into a book?

Q. How did you go about clarifying India’s scale, diversity and multitude of realities, from over a century, into a book?

We took fairly traditional ways in which photography is divided—like photojournalism, street photography, portraiture, contemporary, modernism and art photography—and we slightly adapted them to be relevant in India. Within each genre, we had a shortlist of about 50 photographers and it was a challenge to condense it. Each chapter—and there are 10—could have been a book in itself, but the point of the book was to provide an introduction. It helped having the two of us, discussing it down to the 10 photographers that best represent each genre, and best challenge the idea of a particular genre itself.

For example, the street photography genre is such an American idea… the street means a particular thing in America whereas the street in India is a very different kind of place. So how can you transplant a genre that was born of and was so dependent on a certain kind of street culture in the US? So when we looked at street photography in India, we included public spaces that are not literally the street-side.

Q. Which genre was a tricky one to navigate?

The chapter on ‘contemporary’ was the one that we debated the most, because we don"t have the luxury of hindsight. It’s easy to argue about who has been important to the development of photography or the key people who have influenced styles or genres when you"re looking back. Today, many interesting contemporary artistes are looking at India and we don"t really know what’s going to be the common theme in all of that work, until you can look back in time and explore what it was all about.

For example, one can say that in the 1980s and ’90s, photography globally was a bit tied up with broader intellectual debates around post-modern, using appropriation, staging, reframing things etc as the predominant themes. This fits with what was happening in other intellectual art forms during the same period. But we don"t really know what the current theme is until we can look back. After a lot of debate, we decided the genre needed to show internationalism in a way it hasn"t been before. So, the contemporary chapter has a lot of international photographers, photographers who have created a series that may have begun in another country, travelled through India and ended up elsewhere.

Q. It’s the mark of globalisation.

We are saying that there isn"t and there needn’t be such a thing as “Indian photography”, since the art world has become so globalised. Photographers from India are studying abroad and looking at work being done there. International photographers are making work in India and are no longer bound by the individuality of their country. So we decided this should be one of the defining features of the chapter.

Q. Well, the lines have blurred between photographers and artists.

Yes, we were looking at the aspect of ‘where’ the work was meant to be seen and exhibited. A lot of artists are now making books, they are making works for biennales and other grand stages of art. So the last chapter ‘The Book and the Biennale’ is defined by the audience and the method of display rather than just the ideas and the work itself. But the concept is so loose and the work is so diverse that it was difficult deciding who"s representing photography today and who isn’t.

Then the other challenge was how to place photographers who span so many different genres, such as Raghubir Singh. You could argue that he"s a street photographer, but we put him in the section which looked at modernism because his legacy has more to do with his pioneering use of colour. He pushed photography more towards art, thus engaging the intellectuals in the modernist era. This was more important to us than the fact that he was doing street photography.

Even someone like Sunil Janah, who is very famous for his work documenting tribal communities. Instead, we chose to present his works on India rebuilding itself after independence and industrialisation, even if it isn"t his most iconic or most known project, but is most important for who he is, his political awareness. He did take nostalgic pastoral photographs of tribal women, which are in themselves problematic, but they happened to become iconic. So we had to make these decisions about where to place people in context. Q. If Janah’s name had been taken away from his photographs of tribal women, it may have been mistaken for a colonial point of view.

Q. If Janah’s name had been taken away from his photographs of tribal women, it may have been mistaken for a colonial point of view.

Exactly. Another primary challenge had to do with deciding what to call ‘Indian’. There is the pioneering Indian photographer Kishore Parekh whose memorable body of work is on Bangladesh, not India. Then we have Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the most important 19th century photographers who was born in India, a child of the Empire and had some Bengali blood in her but her works were all made outside India. She"s always been labelled a British photographer because India was a part of the British empire then. We were hesitant of the criticism that would come from showing not just the Indian photographers. So that was a big concern.

Q. But the book’s title makes it clear that it is about photography in India and not about Indian photographers.

The legacy of Magnum photographers and their influence on Indian photographers in the 1980s and ’90s is so fascinating, if we consider photography that exoticises cultures and an elite class that photographed people who were poor. The West may have projected an aesthetic idea of India but it was taken up by the middle-class Indian photographers as well. They knew of the work of Steve McCurry, Marc Riboud, Henri Cartier Bresson, and were influenced by their style. So, in a way, the Indian photographers were self-exoticising too.

It’s the same thing with 19th century British photography. A lot of the photographers who worked on books like People of India (where tribes and races are examined and classified) were Indian as well, who moved in the same social circles as the British photographers. It’s not all black and white that foreign photographers represented India in one way and local photographers did so another. It’s much more complicated than that, and that’s what’s so fascinating. In fact we originally wanted to call the book Photography and India, because it was more about the relationship between photography and India. It is about how photography has influenced India and how India has influenced photography.

Q. I was thinking about the close calls you may have had to take in your selections.

Take Prabuddha Dasgupta, one of the most famous photographers in India. He was predominantly a fashion photographer, a very competent image-maker who made exquisite images, but where was the historical context, the politics, the ‘art history’? We tried to include people whose work engaged more with these kind of questions, who were pushing the envelope, not just stylistically, like Dasgupta did very well, but, intellectually.

Q. The archeology section had some work I had never seen before.

Typically books on 19th century photography in India focus on portraits and architectural ruins What could be more appealing to a publisher than pictures of tribes, women, beautiful landscapes and buildings? Therefore, in most the books on 19th century photography, that’s what you get. But there’s so much more to this early history, there’s Maurice Vidal Portman who photographs just the hands and the knees, incredible in their detail, and not just tribal ‘portraits’. These lesser known works by him are seldom published as they don’t fit well with the idea of what 19th century photography. Then you have photos of architectural fragments by John Marshall in Durham University they"re beautiful and have no colonial agenda. It has more to do with photography taking over from drawing and allowing people to study archeology in a different way.

But people don"t think of this as 19th century Indian photography they think of smokey pictures of the Taj Mahal and things like that. Even the pictures of insects by John Edward Sache... I had no idea people were doing this kind of work. It was nice to go into the archives and see that 19th century photography isn"t only about topographical views but also about flora and fauna and archaeology.

Q. This reminds me of the exquisite drawings in Hortus Malabaricus, the book on Malabar’s medicinal flora by the Dutch during their time here.

Yea, they"re hugely valuable and very collectible. There are ones on birds too. I guess no one thought to see if there was a photographic equivalent. That is what those Sache’s insects are essentially about, photography replacing etching and aquatints and things like that.

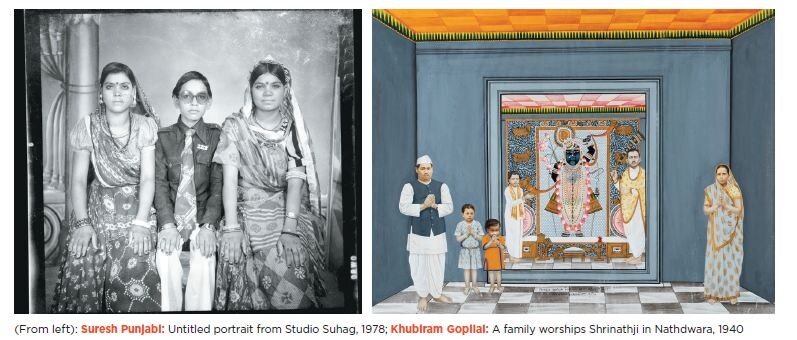

Q. Mary Ellen Marks’s seminal work on sex workers from Mumbai’s Falkland Road is in the book too.

Well, there are issues with it…when you look at Mark’s work in America, she"s always interested in looking at the fringes of society and giving them a voice, which in some ways is commendable. And that is what her legacy is. But in India when she"s photographing sex workers and the Indian circus, there is something awkward about looking at it. You don"t know if it is a good thing that she is bringing these social issues to light or if she"s exploiting them. With the Falkland Road series, a lot of the sex workers are still in their early teens, she"s witnessing a crime. I mean, it is an interventionist question.

Published by Prestel, Nathaniel Gaskell’s book covers 150 years and more than 100 Indian and international photographers. It contains previously unpublished material and work by lesser-known artistes

Q. Is that because the people on the margins she photographed in India aren"t self-empowered to present themselves consciously in the way that her subjects in America in similar situations do?Exactly. People have looked at this work and said it is unkind to the sex workers because that’s not only who they are, that’s one unfortunate aspect of their lives and are now forever branded because of the way she represented them by not giving them a voice.

Interestingly enough, when I told the other photographers featured in the book that we were including her work, they didn’t want to be next to her (in the book) because it is a very contentious series. But I actually do think it is a powerful series. One feels uncomfortable, and makes one aware of a terrible aspect of society. The worst thing one can do with the history of photography is to censor anything. The best thing is to make people aware of the arguments and to understand how much mindsets change over the years—that’s the beauty of art history.

Q. But that was the state of these women, like how they were shown in Mark’s pictures.

The whole point is, the images have become a part of history, and one must be allowed to examine and talk about the images as an ongoing process of understanding. What’s engaging about doing the entire history is that one can take a theme, like exploitation and consent in photography, and examine it from the 19th century’s colonial photography of subjugated peoples, to Mary Ellen Mark in the ’80s and argue that a contemporary work like Soham Gupta’s (of people on Kolkata’s fringes) is exploitative as well. Exploitation is still an issue discussed in photography in India today, and it should be but it is now an issue involving Indian photographers photographing other Indians.

Q. I’m thinking of many such singular, significant photo projects by photographers, even if their larger oeuvre may be irrelevant.

There were many photographers in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s who’ve done fascinating bodies of work which is waiting to be explored academically. When you think about photo-journalism, there’s the famous Raghu Rai of course, but there were so many more. We didn"t have the space to delve into that history, unfortunately. That’s definitely an under-looked part of Indian photo history, and a book in itself that someone should do. Our book is constricted, in the sense that in trying to show the whole history, we perhaps missed out on some of the sub-histories.

Where’s the photographic history of Karnataka? Or even Kerala? I began doing a bit of research on 19th century photography in Kerala. There is so much to do, and no one has done any work on it so far. The writer Manu Pillai introduced me to some members of the Travancore royal family and some historians there. In just the two weeks I spent looking into it, and there was so much photo history in Kerala that is completely unexplored. These archives are somewhere, and just waiting to be researched. And with our museum now, we can start working on all of that.

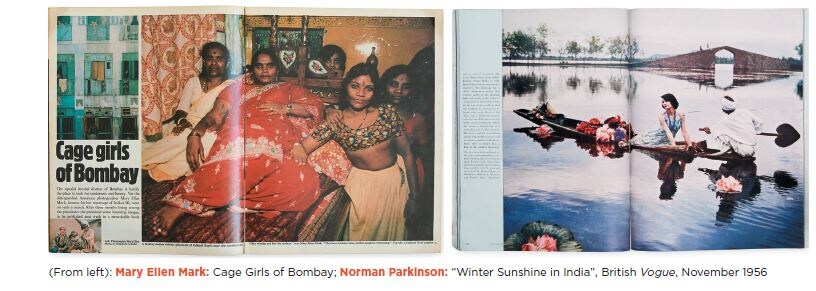

This book is really just the beginning of what the study of photography in India can be. In a decade or two, I’m sure people might look back at our book, and think it to be quite simple in its scope,because there is so much that is missing, lying in archives that yet to be poured out into the public view. We tried as much as we could to bring out works that haven"t been seen, like the 19th century archaeological work, but there’s so much more waiting to be discovered. Take the incredible work of Suresh Panjabi’s photo studio. That is just one studio from one small town in a country that has, god knows, 80,000 small towns. That shows how much stuff is out there.

Q. Suresh Panjabi’s work is wonderful. Reminds me of work of the Nigerian photographer Samuel Fosso that was shown here in 2008.

There are parallels with what was happening in Africa, the new middle class who could suddenly afford photo studios, and were dressing up and putting on their hats and posing with props. It’s the same thing that happens all over the world, I guess.

Q. Well, you are helping build an institution.

The advent of MAP will provide one such institution, which will provide a more serious context for the work of India"s photographic history- that"s the intention in any case. We hope it will make it easier for academics to research its history, exhibitions will raise the profile of certain photographers, and over the long term, it will encourage a greater interest and respect for the medium.

Q. The book is a start, in directing the course of collectors looking at India.

While its purpose is not to encourage collectors but to be a resource for anyone interested in the medium, from a more academic point of view, I think the book might impact collecting of Indian photography by giving a bit more of a formal framework around it. Collectors like to know where the artist they"re collecting fits into the bigger picture. For example, I got interested with Jyoti Bhatt"s work around eight years ago. At that point, his photographs were only really taken seriously by a handful of galleries and academics in India, but he was a long way off from enjoying the kind of fame photographers such as Raghu Rai enjoyed, and there was no market for his photographs.

Since then, through gallery shows, exhibition catalogues, and the fact that museums in the west have begun collecting his work, his archive is now with a formal institution in India. And with this new book, and scholars such as my co-author Diva Gujral doing some of the first serious scholarly research on his photography and where it fits into post-independence modern art in India, collectors are starting to take note. In the next few years he will become one of the main stays on any comprehensive collection on Indian photography. So, after a career spanning a lifetime, it"s been just in the space of 10 years that his market has developed.

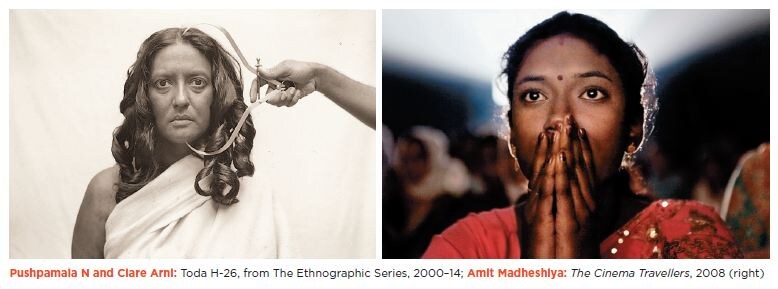

Q. You"ve stated that the artists—no longer photographers now—seem to have freed themselves from the shackles of colonialism, and are pushing towards a diffused international aesthetic. Can you elaborate on this?

What I find most interesting about this entire history is its relationship to the rest of the world and that it began with colonialism and ended with globalisation. No part of this history—by which I mean the reason why photographs in India look the way they do—is independent from India"s relationship with the rest of the world. Photographs and photographers, it seems to me, are either complicit in the hegemony of the West, or they"re consciously reacting against it (such as Annu Matthew or Pushpamala).

Whilst we do say that the work in the final chapter of the book is free from colonial legacy, it is perhaps only at the expense of being a slave to globalisation. We see parallels in lots of work being made in India and in the West, Sohrab Hura and Tillmans, as you point out, Cindy Sherman and Pushpamala, Ed Ruscha and Dayanita Singh (in their comparable use of the book at times). We chose to present international photographers whose work migrates between countries to further show there"s really now a kind of global photography. Perhaps this is contradictory.

Q. There’s the threat of ‘aesthetic gentrification’ where a work is inevitably made "explainable" by adopting a globalised language. A lot of the new work continues to find resonance in photographic trends in the West, be it in styles (like the harsh flash), or framing (like a deliberate weaving of seemingly arbritary images from which one must derive one"s own version of the story).

This might also be in part because of the commercial gallery world and the museum world—it"s hard for work to surface without being part of this world, and it"s in that world"s self interest to promote certain trends and fashions, which make artists conform to this.

All of that said, even if we find traces of influence from canonised Western photographers in the work of contemporary photographers, or people employing tropes and aesthetics from which one can draw comparisons, there is some interesting work that is geographically specific and relies on the photographer having come from a particular place and an in-depth understanding of its subject, and its cultural nuances.

I"d put Gauri Gill in this category. She"s very respectful, very sensitive, and very creative as an artist. She"s also very aware of the history of photography, both Western and Indian, and being conscious of this makes her choices planned and intellectual, and this makes the work all the more layered, her project, "The Americans" being a fitting example. In other words, her work is not at all derivative, but her knowledge of the history of photography in the west and its debates, is very present in her work, and enhances it.

First Published: Apr 13, 2019, 11:13

Subscribe Now