Motley: Still waiting for Godot

After 40 years, and 42 productions, Motley, the theatre group co-founded by Naseeruddin Shah and Benjamin Gilani, is still hungry for more

(Clockwise from top left) Akash Khurana, Jairaj Patil, Benjamin Gilani, Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah share a laugh recounting early Motley days

(Clockwise from top left) Akash Khurana, Jairaj Patil, Benjamin Gilani, Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah share a laugh recounting early Motley days

Image: Aditi TailangLong before a retail chain coined the catchphrase ‘A lot can happen over coffee’, Naseeruddin Shah and Benjamin Gilani, who were in Lucknow for the shooting of Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1978), had stepped out of their “fancy hotel” for a cup of coffee. As they wound up at the Indian Coffee House at Hazratganj, the conversation veered towards theatre. Shah, who had done a few plays with thespian Satyadev Dubey, asked Gilani how come he hadn’t worked in any despite being in Bombay for four years. “Humko milke kuch karna chaahiye [we should do something together],” Shah proffered, and Gilani’s mind flashed back to an extract of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, which he had seen when he was a student at St Stephen’s College in Delhi.

Godot wasn’t a favourite of Shah’s and he had dissed it in an essay while at Delhi’s National School of Drama (NSD). However, Gilani’s insistence and the promise of a production with minimal resources convinced him of the idea. Shah would be glad that it did, for their two-man endeavour, christened Motley, has now turned into a colossus in the theatre landscape. It is celebrating its 40th anniversary in July with Motleyana, a festival from July 16, which features one revival and four running plays of their 42 productions.

Shah and Gilani have greyed in appearance, but vignettes of their youth resonate in the friendly barbs they trade while chatting in Shah’s drawing room, in the company of actors Ratna Pathak Shah and Akash Khurana, among members of Motley’s first core team. “In six well-chosen words,” Shah asks Gilani, this time over a cup of tea, “tell us why you decided to do Godot.”

“They [the other Motley crew] can lie their way out of it and so could I, but I will tell you the truth,” says Gilani, before turning to Pathak Shah. “Isn’t there a line like that in Godot?” Pathak Shah responds with a resounding “no”, but jest soon turns into contemplation as the quartet goes on to narrate how each iteration of Godot has given them new takeaways, even in life. And no one better than Gilani to demonstrate it.

Back in Bombay from Lucknow, Gilani got hold of a script of Godot from TN Shanbhag of the iconic Strand Book Stall and got it cyclostyled. And his first read left him as befuddled as Shah. Theatrically, Waiting for Godot is tricky to pull off, with literary critic Vivian Mercier calling it a play “in which nothing happens, twice”. Even Jennifer Kapoor, Gilani’s co-actor in Junoon, told him they were crazy to be doing Godot. And yet she generously offered him Prithvi Theatre, the performing space in Mumbai that her husband Shashi was building— “It’s yours, take it,” she had said.

“Naseer told me there must be some line in the play with which I could connect. I kept reading it and suddenly realised it was about a few guys waiting for something to happen. What else was I doing, staying in Bombay for four years, waiting for something to happen? That gave us a start,” says Gilani.

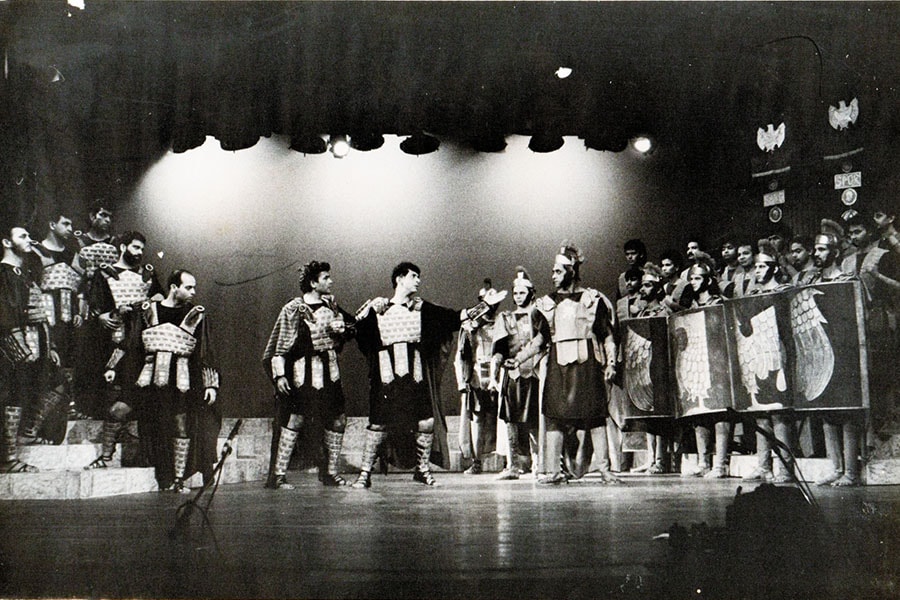

In July 1979, the two, along with the late actor Tom Alter and Roshan Taneja, their professor from the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune (and acclaimed cinematographer Sameer Arya playing the young boy), held their opening show at Prithvi. Gilani had coined the name Motley but it still wasn’t registered, so the first outing took place under Majma, a banner led by the late actor Om Puri. Prithvi was packed to the brim by Taneja’s students, who applauded lustily every time he took to the stage. “The green costume for Pozzo cost us a princely Rs 3,000. Ben and I were wearing rags and Tom had a torn pajama. And there was nothing else but one tree. Years later, Ratna and I had watched Godot on Broadway by paying $150 each. Our entire production cost less than those tickets,” says Shah. A performance of Julius Caesar

A performance of Julius Caesar

Image: MotleyWaiting for Godot has since become one of Motley’s defining plays, with the tagline ‘In Godot we trust’ accompanying the logo for Motleyana. Says Khurana, “Godot is a milestone production for the time spent together, its rigours and the difficulties of communicating a text perceived to be abstract. All of Godot’s revivals evolved. Towards its later productions, it transformed into a black comedy and became more accessible.”

But their repertoire has expanded and evolved from their early barebones outings in the late ’70s and early ’80s to the more expansive, [NSD director] Ebrahim Alkazi-style productions of the ’90s, like The Caine Mutiny (1990) and Julius Caesar (1992), and the story-oriented plays in the following decades. The group also ventured into Hindustani in the noughties, with Ismat Chughtai’s stories in Ismat Apa Ke Naam (2000), a production that Pathak Shah says is her favourite “because that’s where Motley found its groove”.

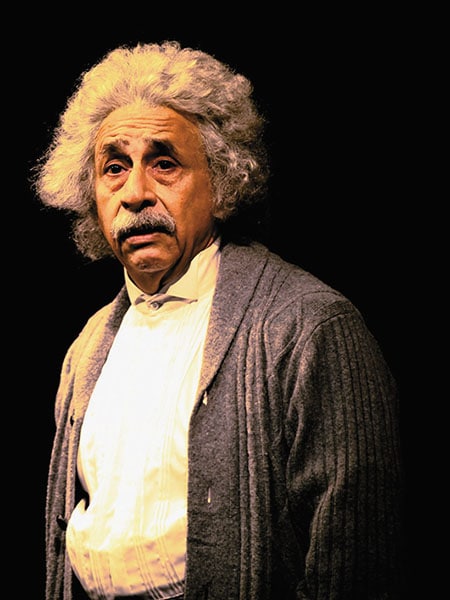

While Shah has always had a wish list of plays to perform, with practicality of production being a principal factor—“I would love to do My Fair Lady, but it’s not practical”—storytelling has been a central theme in his selections. The script of Gabriel Emanuel’s Einstein was locked up in his cupboard for 10 years before he read it, and he was bowled over instantly. Similarly, Salim Arif gave him the script of A Walk In The Woods and Paresh Rawal of The Father, and every time the story appealed to him, he decided to go ahead with it. Akash Khurana and Benjamin Gilani (in front) perform Waiting For Godot

Akash Khurana and Benjamin Gilani (in front) perform Waiting For Godot

Image: MotleyShah is the first to admit that he has sometimes blundered with his choices. Julius Caesar and The Odd Couple, for instance, failed to draw audiences and led to losses. But he took them in his stride and kept looking for compelling narratives. That and Motley’s loyalty to the text draw Arundhati Ghosh, executive director of Bengaluru-based India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), towards the group. Speaking about Ismat Apa Ke Naam, she says: “It was the first time I saw a Hindustani/Urdu play in which the story was told as it was written. Ismat Chughtai is fabulous in her subversiveness, her cheekiness, wit, and ability to play around with patriarchy and feudalism. Heeba, Ratna and Naseer have retained that flavour.”

The last decade has also seen Motley’s gen-next blossom into their own as Shah’s children Heeba, Imaad and Vivaan turned directors with Parindon Ki Mehfil (2015), The Three Penny Opera (2017) and The Comedy Of Horrors (2015), respectively, a transformation facilitated by an easy relationship of equals. “The two generations have come together very well because there is no ageism and thank God for that. We are just a bunch of artistes doing what we love,” says Heeba..jpg) Heeba Shah in Ismat Apa Ke Naam

Heeba Shah in Ismat Apa Ke Naam

Image: Motley Working with the older crop affords the younger ones an opportunity for a masterclass with some of the finest artistes. Heeba recalls watching Dear Liar in 2010 when she realised what fine actors her parents were. “I knew it all the while, but it was the first time it actually hit me while they were performing,” she says. “Through the performance it became clear what they mean when they give instructions like ‘be clear, be detailed, be specific’.”

What brought Shah, Pathak Shah, Khurana and Gilani together, and kept them for 40 years, is their penchant to lavish time on a play before it becomes stage-worthy. By reading, understanding, and repeating the lines over and over again till their essence, as the writer would have wanted it, comes through, even if it takes them six months to make it from the first reading to the opening night. Ratna Pathak Shah and Naseeruddin Shah in Dear Liar

Ratna Pathak Shah and Naseeruddin Shah in Dear Liar

Image: MotleyActor Rajit Kapoor, who performed with Shah in A Walk In The Woods, recalls their research to portray the role of bureaucrats, including travelling to Delhi to meet some and understand the responsibilities of an IAS officer. Says Shah: “Actors have a tendency to start acting at the drop of a hat. I don’t believe in the nonsense of actors becoming characters. Get them to understand what they are saying and only then you can make progress.”

Shah himself took a year and four months to perform a second rendition of Godot as he felt their first performance was sub-par. Through those months, Gilani and he decided to approach it like music, “a symphony of words”. “Forget about understanding, we said, let’s speak these words as beautifully as we can,” he says. Sense only began to emerge when they stopped trying to understand.

“And yet we discover,” says Pathak Shah, “that five years after we’ve been performing a play that we haven’t really understood it, and it reveals so much more. We figure out that maybe we’ve been doing it wrong all this while.”

In its early years, Motley didn’t frame a grand mission statement neither when Shah and Gilani co-founded the group in 1979, nor when Pathak Shah and Khurana joined them by the mid-’80s. Theatre wasn’t a means of livelihood, but of deep passion, one that propelled them to perform even for an audience of seven people at a Mumbai auditorium, resume when Om Puri’s father and his friends walked in from the backstage in the middle of the show or even after a Bengaluru resident interrupted a sold-out show, demanding to know who parked their car in front of her house.

“We are probably remnants of the generation that did things just because. We didn’t have a big plan or financial backing. We came from a time when people had the time to breathe and think,” says Pathak Shah. When they weren’t rehearsing at the homes of friends, the Motley crew would practise their lines walking on Juhu beach, at restaurants until they were asked to leave, or on the top tier of double-decker buses. “If you boarded at Santa Cruz and got off at Fountain, you could complete the whole first act of Godot,” she adds. Naseeruddin Shah in Einstein

Naseeruddin Shah in Einstein

Image: Motley In those years, while Shah had designated himself as the group’s chief creative director and Gilani the spokesperson, each of them chipped in with whatever was needed. Before Prithvi got its ticket-selling licence, the actors would stand with a jhola for collections Gilani once fled with it after noticing a Rs 20 note, fearing its owner had dropped it by mistake and would return to take it back. While producing Arms And The Man, he organised furniture from South Mumbai, as there wasn’t any available to hire in the suburbs, while Pathak Shah “would do what no one else wanted to”, phoning up people, organising food, shopping for costumes at Chor Bazaar and getting out of the way when tempers would fly. “Like Gogo and Didi of Godot, Ben and Naseer are really an old, married couple. Best for a third party to stay out of the way,” she laughs.

But such an ad-hoc fashion of operation wouldn’t have lasted for long and in 1992, the backstage responsibilities were handed over to Jairaj Patil, who used to be Shah’s make-up artiste. From designing

sets, to accompanying Shah to rehearsals and Pathak Shah for scouting properties and costumes, to handling lights and music, Patil is Motley’s go-to man. He has executed plans for Dubey, who would come prepared with a set design along with the script, and has had to firefight for Imaad’s The Three Penny Opera, where he took charge of set design just a month before staging and completed it in eight days.

Patil’s backstage team rehearses as much as any other actor. “When we did The Truth, there were 12 people backstage, who changed sets in the dark and left before anyone got a whiff. The audience only got to know at the curtain call, when they appeared on the stage along with the actors,” says Patil.

It comes from Shah’s emphasis on preparation—from the lines to how the sets would transform between acts—to avoid last-minute nerves. “The only actors who are nervous are those who are not well prepared,” he says.

Its 40-year arc has given Motley a glimpse of theatre’s changing audiences, from the crowd of “grey-haired people” to youngsters who ask them if they could join the group. Shah has a high benchmark for his actors and would cast “only those he could trust with his life”. It breaks his heart to tell the youngsters there are no vacancies, but he is enthused by the numbers that turn up for performances.

Says Pathak Shah, “We didn’t start the way you see us today. The quality of our earlier work was pretty iffy. Which is why when people look to us for advice, I say you are looking at us at the wrong end. We were exactly like you when we started. You have to do it yourself and figure it out.”

In these 40 years, Shah says he has received a bounty of lessons from Motley. “Dubey and Alkazi both used to say theatre is not a democratic process. I had no reason to challenge the statement at that time. But I do think it can be. Theatre does need a guiding vision, but not a dictator. I was way too harsh on my actors, and that was not good. Besides, my ideas on theatre have clarified to the point where I know exactly the kind of theatre I want to do and the kind I don’t.”

What does the audience want of Motley in the next decade? More original productions and explorations of Indian writing, like Amrita Pritam or Nabarun Bhattacharya, says Ghosh of IFA. And what does Motley want for itself? More of the same. Plus, adds Khurana, “A kind of total contrast to what is known as physical theatre, where you communicate through stillness and words.”

Clearly, there’s no stopping Motley even at 40.

First Published: Jul 13, 2019, 07:59

Subscribe Now