For exiled authors, the ink never dries

For writers such as Perumal Murugan, Taslima Nasrin and Sharmila Seyyid, continuing to write shapes their creative process and response to persecution

Protesters burn an effigy of author Taslima Nasrin in Kolkata in 2004

Protesters burn an effigy of author Taslima Nasrin in Kolkata in 2004

Image: Jayanta Shaw/RetuersNineteen months of being “a walking corpse” changed Perumal Murugan as a writer.

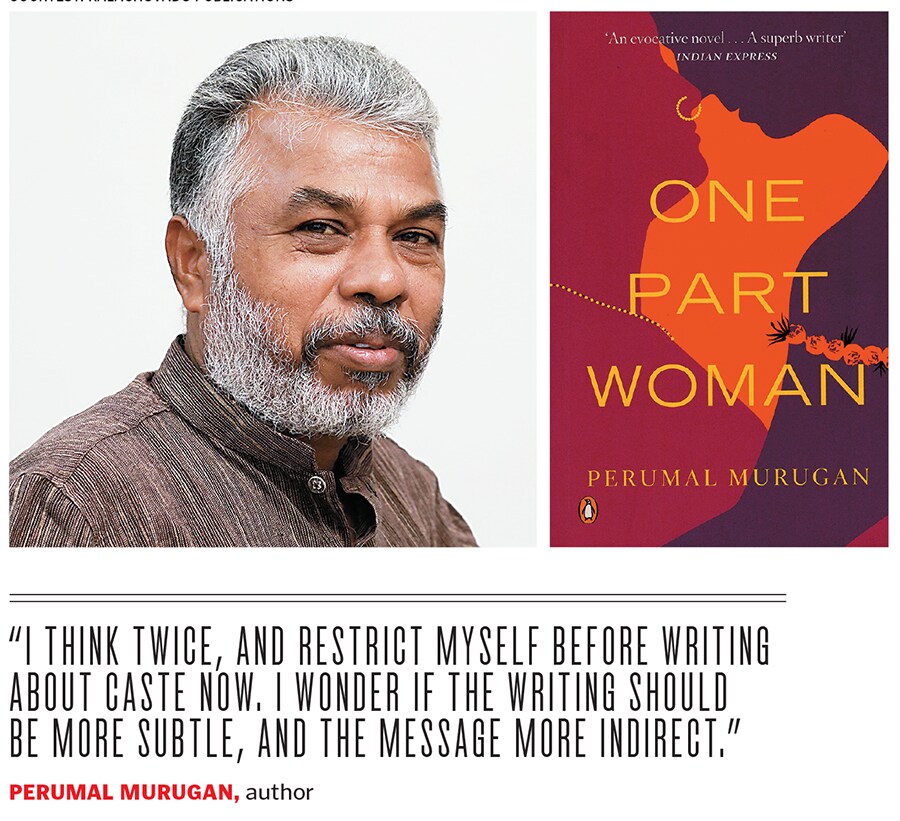

The ordeal of his exile, as he calls it, ended when the Madras High Court, in July 2016, ruled that the Tamil author must be “resurrected to what he is best at: Write”. According to Murugan, those words comforted a “heart that had shrunk itself and wilted”, as they upheld his freedom of expression against violent caste groups that had claimed his novel Madhorubhagan (One Part Woman) hurt religious and social sentiments. The protestors, with support of the local administration in his hometown Tiruchengode, had extracted a written apology from the writer, forced him to delete controversial portions of his book and withdraw it from stores. Murugan and his wife Ezhilarasi, both professors of Tamil literature at the Government Arts College in Namakkal at the time, had to abandon their home of 17 years and relocate to Chennai along with their two children.

So while the court ruling did more than just bring Murugan out of exile—it gave the 53-year-old author a new lease of life and career success—the persecution has drastically altered his creative process. “I think twice, and restrict myself before writing about caste now. It wasn’t the case before, when I wrote frankly, without fear,” says Murugan, on the sidelines of the Kerala Literature Festival in Kozhikode in January, where he was speaking about Amma, his first nonfiction work translated into English. The book is a collection of essays that pay tribute to his late mother Perumaayi, while giving a glimpse of agrarian life in Tamil Nadu.

“Even if I do write about caste, I wonder if the writing should be more subtle, and the message more indirect,” says the author of 11 novels, five collections of short stories and five anthologies of poetry. Most of these works were deeply political and offered searing commentaries on class divides and caste hierarchies of rural India. Murugan does not like reminiscing about the period when he had declared his ‘death’ as a writer, or the events that led to it, but admits it was a time when he had become numb to the world around him, and could not manage to write anything for the first three months.

Kannan Sundaram, the publisher of Murugan’s Tamil works who stood by the writer through his tribulations, believes that the exile caused a dramatic turnaround in Murugan’s writing. “He tells me that he wants to write about asuras [demons] and not human beings. His next novel is based on an urban middle-class family and, for the first time, does not have a rural context,” says Sundaram, managing director of Kalachuvadu Publications. “Murugan will continue to take on social concerns, but he wants to employ different literary tactics like humour and sarcasm to sidestep controversy.”For instance, in Poonachi, Murugan writes about a black goat having to get its ears pierced as a marker of identification, when authorities start making a register of goats. Doesn’t it seem eerily similar to the ongoing National Registry of Citizens? “It is a work of fiction, but at times, there are many chances of a writer’s imagination turning into reality,” he smiles. “I do not write with the plan of creating social awareness, but my writings are born out of life experiences with caste and other hierarchies, and the people it affects will always react to it.”

*****

Writers who speak against established social, political or religious orders have sometimes found themselves persecuted and banished from their own land. Whether this exile is self-imposed or not, the writing that emerges from it reflects the effects of the uprooting on their lives and work, and can result in memorable pieces of literature. Be it Italian poet Dante Alighieri who wrote his seminal work Divine Comedy after being driven out of Florence, Italy, in 1302 for supporting the Roman Empire instead of the Papacy, or French author Victor Hugo, who wrote a major portion of Les Miserables, considered one of his finest works, while in exile in Guernsey, an island off France’s northern coast, for opposing ruler Napoleon III in the late 1850s.Image courtsey: Kalachuvadu Publications[br]

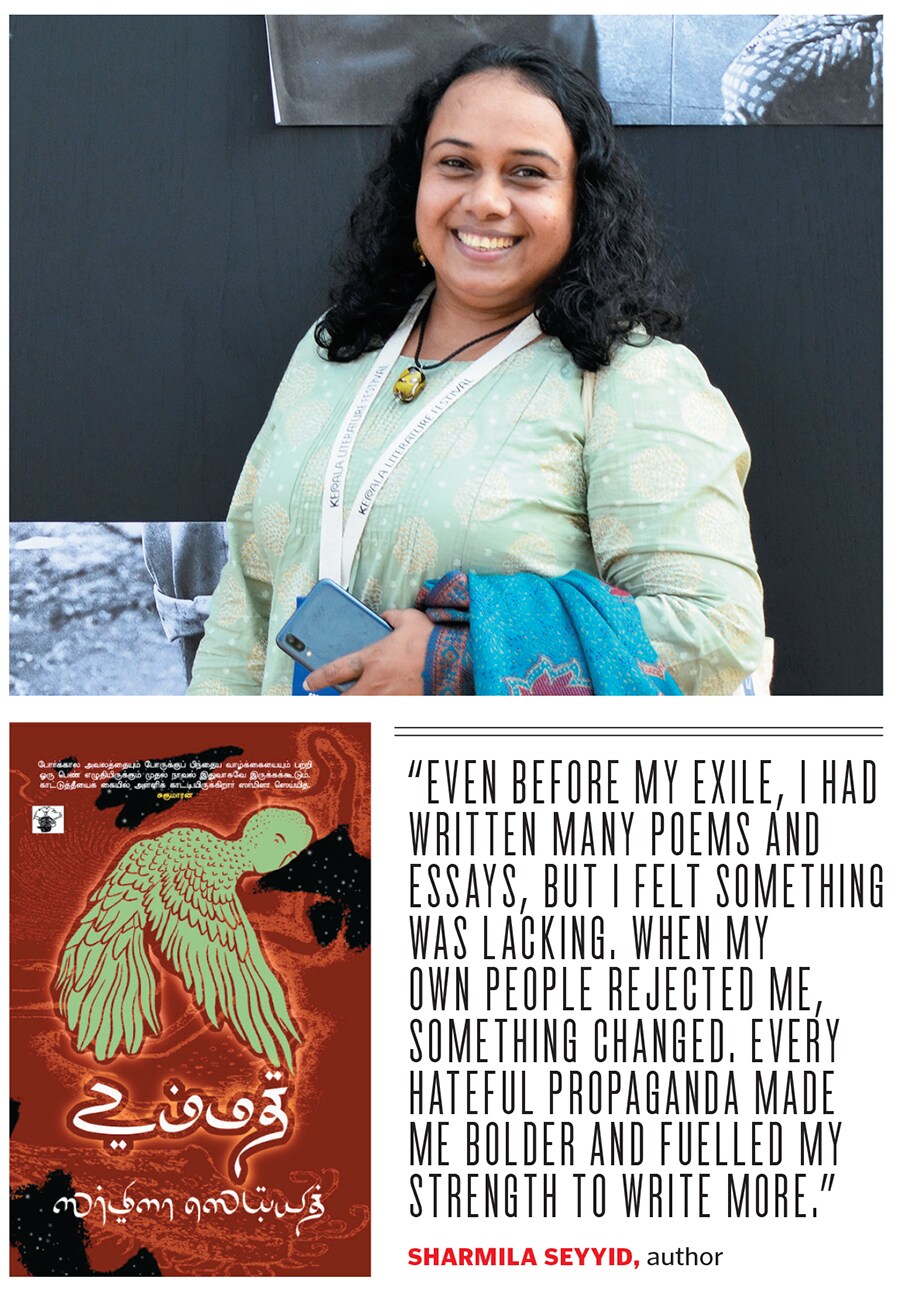

For Sharmila Seyyid (37), continuing to put pen to paper was the “only thing that healed and protected me from the hatred, and the loneliness that comes from being stateless”. The Sri Lankan author and activist, who is a single mother, took refuge in Chennai with her two-year-old son for over three years after she was chased out of her hometown Batticaloa in 2012. A televised interview about one of the Tamil poems in her collection Siragu Mulaitha Penn (The Woman Who Grew Wings) about the rights of sex workers was construed as an endorsement of prostitution by mullahs and Islamic fundamentalists in Sri Lanka.She started getting threatening phone calls and was publicly chastised for not wearing a purdah (veil). An English-medium primary school she ran in Eravur was attacked, while morphed photographs of her being raped and killed was circulated on social media. “I saw the news of my death. I wrote many poems about it,” says Seyyid, who adds that while the Sinhalese in Sri Lanka were against her as she was a Muslim, the Muslim community cast her away as an outsider.

“Even before my exile I had written many poems and essays, but I always felt that something was lacking. When my own people rejected me, something changed. Every hateful propaganda made me bolder. It just fuelled my strength to write more,” she says. Although Seyyid has returned to Sri Lanka, she now lives in Colombo and keeps moving house every three or four months, given the continuing threats.Image: Rashmy Ahamed[br]

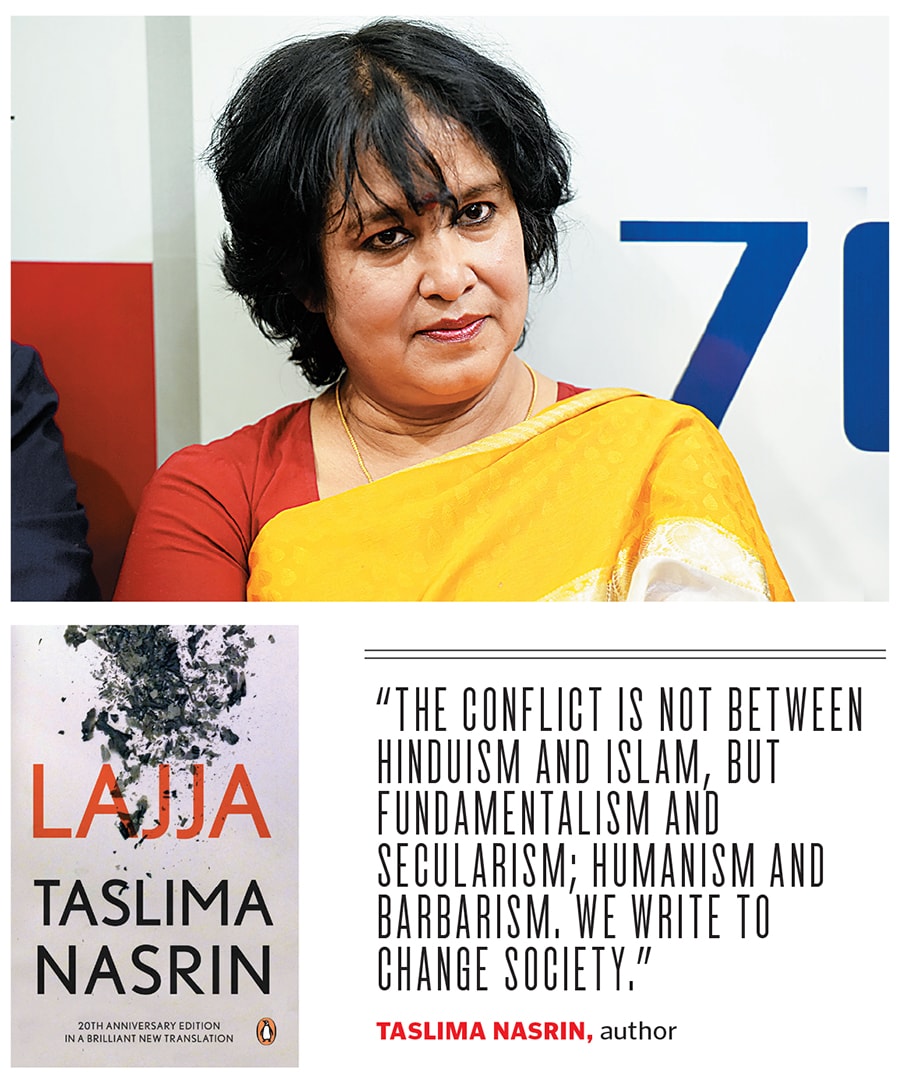

While in Chennai, an English translation of Seyyid’s book Ummath, about the injustices faced by women against the backdrop of the Sri Lankan civil war, was published by HarperCollins. Gita Subramanian, the novel’s translator, has seen Seyyid build her life afresh in Chennai, put her son in school and get a Bachelor of Social Work degree from Stella Maris College, all while continuing to write. “She was always a positive person even in the worst of times, but when she wrote Ummath, there was a lot of anger in her that reflected in her writing. Over time, with the experiences of meeting people, travelling and being recognised in countries like the US, she seems to have become calmer and happier. The confidence in her work and personal life has grown since those days.”Seyyid, the author of four books, is now writing a non-fiction book about the Easter bombings in Colombo last year, scheduled tentatively for an April release. She says the only way forward for writers like her is to soldier on with their causes, while keeping their core sensibilities intact and making their voices even louder.Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasrin (57), in a chat at the Kerala Literature Festival, also swears by this approach. “There is an ongoing conflict,” she says about why she continues to write despite the odds. “But the conflict is not between Hinduism and Islam, but religious fundamentalism and secularism between rational, logical minds and irrational blind faith between humanism and barbarism.” Her columns on patriarchy, and her novel Lajja, which spoke of religious fundamentalism against Hindu minorities in Bangladesh, resulted in Islamic groups throwing her out of her country in the 1990s. She later received a permit to stay in West Bengal in the late 2000s, only to be ostracised by the Left government.

According to Premaka Goswami, senior commissioning editor, Penguin Random House India, Nasrin’s close association with the people of India, especially when she sought refuge in Kolkata in 2008-2011, contributed immensely to her writing. “To her, language, literature, arts, society and culture are palpable. They are living entities and she needs to closely engage with them every day. Her memoirs, fiction and poetry turned out to be more and more artistically subtle, aesthetically evolved and sharper during exile.”

Penguin Random House India, which published Lajja and French Lover, will now translate 12 of Nasrin’s books, including her autobiographical writings, essays, fiction, short stories and poetry, and publish them in 2021. Ghosh believes that while her position on women’s rights and religious fundamentalism continue to find characteristic voice in her writings, the exile has also resulted in poems on love, loss and longing, which remain underappreciated. “Most of these poems are still in Bengali, and a wide spectrum of readers do not have access to them,” he says. Image: Amal KS/Hindustan Times via Getty Images[br]Nasrin says that if there was no threat to her life, her writing might have been something else altogether. “Maybe, this kind of threat, the pain and the isolation made me a different person. But I don’t mind, because for me, writing has always been a simple act of conveying whatever I feel.” She, however, believes that with or without support, she will continue doing what she is best at: Socially-committed writing. “If we go shut our mouths, nothing is going to happen. We write to change society.”

Image: Amal KS/Hindustan Times via Getty Images[br]Nasrin says that if there was no threat to her life, her writing might have been something else altogether. “Maybe, this kind of threat, the pain and the isolation made me a different person. But I don’t mind, because for me, writing has always been a simple act of conveying whatever I feel.” She, however, believes that with or without support, she will continue doing what she is best at: Socially-committed writing. “If we go shut our mouths, nothing is going to happen. We write to change society.”

*****

According to Geetha V, co-director of Tara Books that has published translations of Murugan’s Koola Madari (Seasons of the Palm) and Nizhal Muttram (Current Show), there is no one way to dealing with power that seeks to curtail creative speech. “I think writers deal with fear, anxiety and bewilderment of being hated in different ways… the examples of what writers have done, especially in the Soviet Union and Latin America, should prove instructive.”

While writers in exile have been brave and tenacious, publishers are also doing a lot more to support them by being open-minded about different kinds of content and viewpoints, experimenting with genres and facilitating more public dialogue and awareness around books, adds Mita Kapur, founder and CEO of literary consultancy Siyahi. “The situation is far better than it was, say, a decade ago. Everybody is being careful and follows in-house mandates and frameworks before taking the call to publish, but that hasn’t really deterred the industry from moving forward and taking the plunge.”Even the state has a role to play in standing by writers instead of giving in to the demand of violent mobs, believes Sundaram. “But it never really does that, and instead of protecting the writer, they abandon them.” Seyyid says the literary community needs to be united to create a robust support system for writers under duress.

Penguin Random House—which has published works of exiled authors like Nasrin, Murugan and Salman Rushdie—agree that while there are indemnification clauses that obligate authors to take responsibility in the event of a lawsuit from a third party, there is a moral imperative and ethical obligation for publishers to stand by their authors. Mansi Subramaniam, executive editor and head of literary rights, says fighting persecution should never be a burden on the writer alone. “There is a community involved, including stakeholders like journalists, lawyers and readers... anyone with a serious investment in the freedom of expression. It is everyone’s responsibility.”

("‹The writer was in Kozhikode on the invitation of the Kerala Literature Festival)

First Published: Feb 29, 2020, 09:36

Subscribe Now