Cricketer Henry Olonga on the moment that changed his life

Former Zimbabwean cricketer Henry Olonga talks about his career on the field, and the protest that changed it all

Henry Olonga wore a black armband before the 2003 World Cup match against Namibia to protest against the ‘death of democracy’ in Zimbabwe

Henry Olonga wore a black armband before the 2003 World Cup match against Namibia to protest against the ‘death of democracy’ in Zimbabwe

Image:Alexander Joe / AFP via Getty ImagesA part of the golden generation of Zimbabwean cricket of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Henry Olonga stands tall as one of the most audacious figures of the game. The country’s first-ever black cricketer, Olonga played 30 Tests and 50 ODIs in a career spanning eight years, picking up 126 wickets across both formats.

Olonga, aged 18, became the youngest to represent his country when he made his Test debut against Pakistan in 1995. From ruffling Sachin Tendulkar’s feathers in Sharjah in 1998 to causing an upset in his 1999 World Cup encounter against India, he was on course to becoming Zimbabwe cricket’s poster boy, when his career was cut short by an incident that would define his legacy more than anything.

In 2003, Olonga alongside captain Andy Flower staged the famous black-armband protest in their opening match against Namibia at the World Cup to mourn the “death of democracy” in Zimbabwe. The protest came in the wake of white farmers’ lands being seized forcibly in Zimbabwe by the Robert Mugabe-led government, and the rise in cases of human rights abuse.

There were serious repercussions for both Olonga and Flower. Both never played for the country again, and Olonga retired prematurely from international cricket. Initially charged with treason (punishable by death in Zimbabwe), Olonga faced multiple arrest warrants and death threats. He fled the country in 2003 and lived in exile in Britain for 12 years.

Olonga moved to Australia in 2015, where he now lives in Adelaide with his wife, Tara, and two daughters. After catching the imagination of the audience and judges at The Voice Australia, a singing competition, in 2019 with his beautiful rendition of Anthony Warlow’s This Is The Moment, Olonga today is a successful opera singer.

Labelled as a ‘traitor’ by some and ‘hero’ by others, he continues to divide opinions in his own country like no one else. In an interview with Forbes India, he talks about his playing days, the protest, and what followed.

Q ICC suspended Zimbabwe Cricket in July as the cricket board was unable to keep out government interference, and then reinstated them again. With Mugabe’s death, are you hopeful about the future of Zimbabwe cricket?

I was very disappointed when ICC did what they did. Zimbabwe was the first country in the history of ICC to be suspended in that manner. In the past, other countries have been warned or told to get their house in order, and ICC has ensured they can continue to play. It was a wrong time for ICC to be doing something like this because Zimbabwe is one of three proud cricketing nations [along with South Africa and Kenya] in Africa. From a cricketer, Olonga is now a successful opera singer in Australia

From a cricketer, Olonga is now a successful opera singer in Australia

Image: Patrick Eagar/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images

Where is Kenya in world cricket now? They are gone. No one hears about them. And this is the nation that made it to the semi-finals in the 2003 World Cup. That was an extraordinary achievement by Kenya. To see it languishing is very disappointing. To see Zimbabwe going in a similar direction is equally disappointing. It makes you wonder if ICC really understands how precarious African cricket is at the moment. African cricket can just die if they don’t take care of it.

I understand ICC’s problem on the whole issue, that they don’t want political interference in the sport. But it seems odd that the man they are backing is also very political. Zimbabwe cricket has struggled under the last few leaders who have run the board. You look at the former Zimbabwe cricket chairmen Peter Gingoka and Ozias Bvute. They mismanaged millions of dollars, and yet ICC kept backing them. So, the ICC keeps backing people who get along with them.

Now that ICC has reinstated Zimbabwe, I am a little hopeful. But then again, we are losing a lot of players. Hamilton Masakadza has retired, while so many players have gone overseas for better opportunities. Good players like Sikandar Raza are being dropped because of disciplinary issues. We have stopped being competitive. We went on a tour recently to Ireland and Holland and got beaten by teams we should be dominating.

Q You had to remodel your bowling action very early in your career. Did that affect you in any way?

Well, it took me three years to fix my action. I spent some time in India, Australia and South Africa, at the end of which I was a half-decent player. I did well in a Test against India in 1998 I took a five-wicket haul. That’s actually what kickstarted my career. I then went to play ODIs in Sharjah. I did great in one match there, when I got Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid. Then in the next match, Tendulkar got his revenge.

Then we went on a tour of Pakistan where I was ‘Man of the Series’. We won the series, and it was a big thing to win a Test series in Pakistan. And then I did well in the 1999 World Cup and a couple of more years after that, I retired after the black-armband incident.

Ultimately, the remodelling of my bowling action made me a better player.

Q Zimbabwe finished in the World Cup Super 6s in 1999 and 2003, and things seemed smooth. How did it go so wrong for Zimbabwe cricket?

When I did the black-armband protest with Andy Flower, Zimbabwe cricket lost Andy and me. Guy Whittall had announced his retirement after the 2003 World Cup. After that, white players decided to boycott playing because team selectors were giving preferential treatment to black players. Cricket was white-dominated when I started, and the administration wanted to have more black representation. The white players said it was not fair and players should be picked on merit. In 2004, the administration sacked captain Heath Streak, prompting a walkout by 14 other players in protest against political influence. Zimbabwe cricket effectively lost about 14 good players, and we never recovered after that.

Q Your and Flower’s protest was a bold and gutsy move. Were you aware of the consequences?

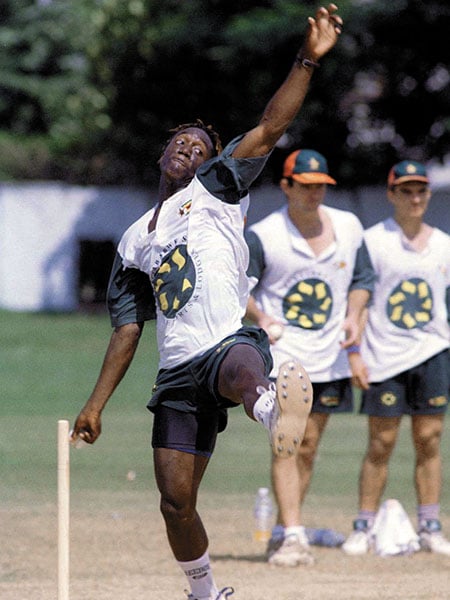

Oh, yes. We knew the consequences. We did this 16 years ago. Long story short, we understood the situation in Zimbabwe and what Robert Mugabe was like. We wanted to protest. So, we met a few people to discuss the risks and potential fallout. We were aware about what was at stake and what kind of reaction we’d get from the government. We were advised by many people not to do it, with everyone saying it would not end well for us. Olonga during a practice session in Dhaka during his playing days

Olonga during a practice session in Dhaka during his playing days

Image: Sunil Malhotra/ReutersBut we were young and bold. We had a cause and we stuck to it. But I will say that the consequences far outweighed what we did. What we did was to criticise the government and their reaction was way over the top. But that’s politics for you in Zimbabwe. Some people love us for what we did, some of them hate us.

Q After the protest, you moved to England and then to Australia. How is life away from your home country? Do you miss Zimbabwe?

Yes, I miss certain aspects of Zimbabwe, but it is now a different country to the one I left. It has struggled economically a lot in the last few years. I have moved on in a sense that I am a completely different person now. I have got British citizenship, and I will soon be a citizen of Australia as well. So, my allegiance, in a sense, has changed.

Zimbabwe has given me a lot of hate. I have received a lot of love from a lot of people as well, but if you see my Twitter timeline from a few months ago, you will see many people in Zimbabwe giving me grief. So, it makes it hard to consider going back or consider a future there. But I do follow the developments in the country, and I am a keen fan of Zimbabwe cricket. It’s a beautiful country but it’s a troubled land.

Q You bowled to a lot of great batsmen. Who was the toughest?

I reckon Tendulkar’s up there, but I didn’t bowl much to him. I found it extremely difficult to bowl to Marvan Attapattu. He kept making double hundreds against us. He was an unbelievable player who just seemed to bat for hours and hours against us. He scored three double centuries against us. Now, of course, there are many other great players. In addition to Marvan, there was Sanath Jayasuriya, Brian Lara, Mark Waugh, Steve Waugh and Jacques Kallis. Most countries had one really difficult batsman who had an attacking style.

Apart from Tendulkar, India had Dravid and Ganguly who were great world-class players. Oh also, I forgot about Virender Sehwag.

Q Did you idolise any cricketer when you were growing up?

Yes, I think Malcolm Marshall was up there. He was a great bowler but Alan Donald was my hero. I loved the way he played the game. I loved the way he bowled. I loved his bowling action and aggression. Great player. I really admired him a lot.

Q From the current generation of bowlers, who do you think has got the biggest potential?

There’s obviously Jasprit Bumrah from India. In addition to him, you have got Kagiso Rabada, Pat Cummins and Jofra Archer. Rabada needs to control his temper. He just gets into trouble with match referees very often. If he can control that part of his game, he has got an unbelievable potential.

Q Do you have any regrets about your cricket career?

I got no regrets, to be very honest. As a bowler, it would have been nice to get a few more wickets. It would have been nice to take another hundred wickets, I reckon. I wouldn’t say that’s a regret. It was not meant to be and that’s okay. I wasn’t a disaster as a player, but it would have been nice to scalp some more wickets.

I also don’t regret the black-armband protest, and I don’t regret that my career came to an end because of that. It may well have come to an end a year later anyway because of what was going on in Zimbabwe. So, it’s not something I regret in itself but I know that one moment changed my life.

First Published: Dec 21, 2019, 14:35

Subscribe Now