Mattel Continuously Innovates to Keep Barbie Alive in a Tech World

In an era when iPad apps and videogames practically demand children's attention, Mattel continues to lead by innovating with its old-school plastic playthings

Head 10 minutes south of Los Angeles international airport on the 405, exit at El Segundo and you’ll blunder upon a 200,000-square-foot concrete bunker lurking among the strip malls in this seedy bit of Los Angeles County. The low-slung structure, surrounded by a black iron fence, was once an aircraft parts factory. It now houses the design laboratories of Mattel, Inc, the world’s largest toymaker, and deep inside the high-security facility, a crack 12-person team of screenwriters, computer animators, comic book artists and industrial designers are busy engineering the next great American toy: Max Steel.

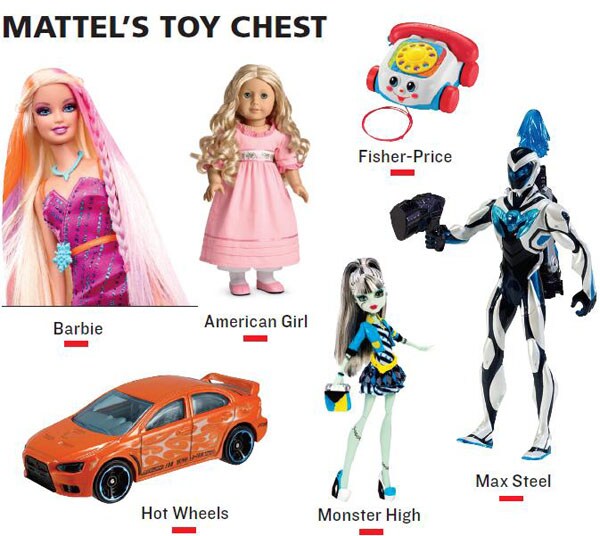

In physical form, Steel will be a 6-inch plastic superhero action ï¬gure, with a well-developed backstory: His mission is to harness the turbo energy he possesses to morph into different cyborg forms and save the world from monsters bearing names like Elementor and Dredd. And, just like Superman, he has a mild-mannered alter ego: Maxwell McGrath, a 16-year-old high school kid with brown hair and a square jaw.

The Max Steel doll won’t be appearing on US retail shelves until August, but his launch is already well under way. Pull up maxsteel.com and you can play the Max Steel: Hero’s Journey videogame, watch videos introducing him or download a Max Steel mask. In March, a Max Steel cartoon premiered on Disney’s XD digital cable and satellite channel and will soon be available in more than 100 different markets worldwide. Toys used to spring from entertainment. Now entertainment supports the toys. “Having an action hero that’s on for a steady basis—on television, on webisodes, on digital—is going to create a more consistent demand for that product,” says Mattel’s chairman and chief executive, Bryan Stockton.

Stockton, who is 59 and has been Mattel’s top exec since January 2012, is referring to Steel, but it is no small irony that his 15th-floor office with views of the Paciï¬c and the Hollywood Hills is decorated with a dozen or so glass-encased Barbie dolls, each mounted on its own personal pedestal. They deserve to be there. Because for many decades, Barbie was Mattel and Mattel was Barbie.

Barbie is more than a toy for the last 54 years, the 11.5-inch moulded-plastic doll has been a deï¬ning feature of American girlhood. She is also a money machine. Just click over to Amazon.com. Princess Barbie, Astronaut Barbie, Paleontologist Barbie and President Barbie—some 45,532 products, all for sale.

But Barbie’s improbable ï¬gure, her piercing blue eyes and her youthful blonde mane mask the fact that she’s been showing her age on Mattel’s ï¬nancial statements for more than a decade. Last year Barbie’s global sales declined 3 percent to an estimated $1.3 billion worldwide. In the US, she is doing even worse. Barbie’s domestic sales have dropped a stunning 50 percent since 2000, according to Gerrick Johnson of BMO Capital Markets, down to $460 million in 2012. Barbie now represents 20 percent of Mattel’s $6.4 billion in revenues versus 30 percent 10 years ago.

Stockton hopes Max Steel will join Mattel’s other promising toy franchises—Monster High and American Girl—in smoothing Mattel’s way in a post-Barbie world. The task is important because some of Mattel’s other key franchises—its Matchbox cars and old Fisher-Price line—are under pressure. Their sales have fallen for nearly a decade. Then there are more existential threats, like a digital generation that favours 99- cent iPad apps over traditional toys, a shrinking number of toy stores and the looming concern that DIY 3D printing will render premade plastic toys obsolete.

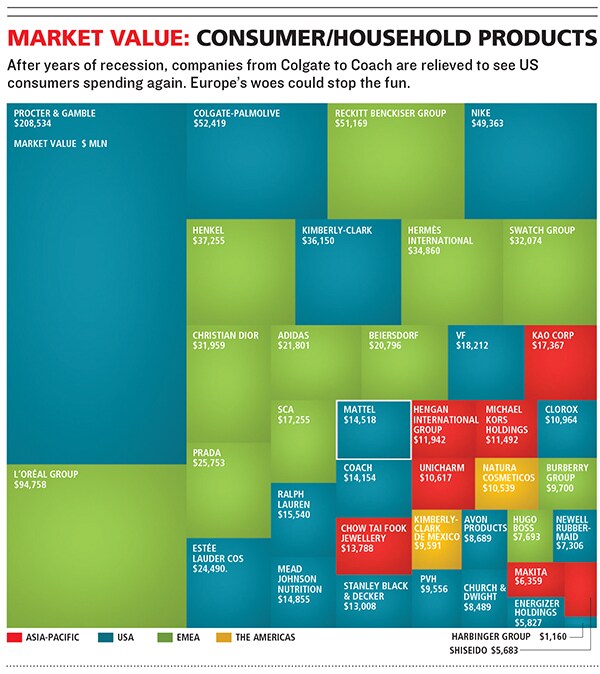

Today Mattel controls 16 percent of the $20 billion US toy market, nearly double the share of its closest competitor, Hasbro. It has a portfolio of strong brands besides Barbie, including Barney, Thomas & Friends and Hot Wheels.

But to keep growing, Mattel needs a steady diet of fresh new hits, including, the company hopes, Max Steel. It’s a big bet but not as risky as it might seem. In fact, for the last 11 years, the action ï¬gure has been selling like hotcakes outside of the US. A Spanish-speaking Max Steel, who is older, has been available in South America since 2001, the year Mattel removed an earlier version from US stores because the company felt the toy’s terrorist ï¬ghting themes were too controversial for American kids in the wake of 9/11. Latino Max already generates more than $100 million in retail sales per year.

Steel’s target audience of younger boys, ages 6 to 11, responds well to videos and the recycled story plots available online. Max Steel’s rollout compresses an 18-month traditional schedule down to less than a year, and unlike it did with Barbie of old, Mattel is paying decidedly more attention to Max’s narrative arc. It wants a slow story reveal to build interest. “When we built Max Steel, we tried to think about how many different ways can this character come to life,” says Timothy Kilpin, Stockton’s creative director for Mattel’s franchises. “You’ve got to know where the brand is going 18 months from now in terms of a storytelling aspect.”

In 2012, Stockton’s ï¬rst full year at the helm, Mattel’s sales climbed 2 percent to $6.4 billion and proï¬t increased 12 percent to $864 million, excluding a one-time litigation charge. “Even if you think the sales growth is lacklustre, Mattel is doing better relative to the industry,” says BMO’s Johnson. Mattel stock climbed 32 percent in 2012 versus 12 percent for Hasbro and a 10 percent decline for Jakks Paciï¬c. It handily beat the S&P 500, which was up 12 percent. The company has modest debt and an enviable cash pile of $1.3 billion. And when it comes to international diversiï¬cation, Mattel is a shining example of how to execute well, with about 50 percent of its revenues coming from outside the US.

Stockton can take much of the credit for Mattel’s impressive global footprint, having led the company’s international business for eight years, until shortly before he was named chief executive. He came to Mattel after a 24-year career in processed foods, ï¬rst at Oscar Mayer and eventually Kraft Foods. The son of an Indiana University B-school professor, Stockton earned his BS and MBA in under ï¬ve years at Indiana University. He then landed an entry-level position in management at Oscar Mayer in 1976. There he learned nearly every aspect of its business, from buying hogs and slaughterhouse operations to efficiently pricing grocery items like bologna. After Kraft was taken over by Oscar Mayer’s parent, Philip Morris, in 1988, Stockton worked with Kraft’s group vice president Robert Eckert. It was Eckert who convinced Stockton to join him at Mattel soon after Eckert was named chief executive in 2000.

Compared to food, Stockton loves the toy business’ high margins, its low capital investment and its short cycles. “We go from ideas to cash in about 18 months,” says Stockton.There are three ingredients to Mattel’s continued success: Launching new, richly developed products like Max Steel efficiently milking mature franchises like Barbie and continued overseas growth. “The global middle class is expected to grow from 569 million households in 2011 to 766 million in 2020,” says Stockton, who describes his motto in Mattel’s 2012 annual report as “happy but never satisï¬ed”.

With a smile on his face, Stockton describes how he has already overhauled Mattel’s corporate structure, dismantling what was a siloed operation by centralising product design, marketing and distribution. Along the way, Mattel has shed $400 million from expenses since 2009, pushing gross margins up to 53 percent from 50 percent.

Besides the company’s infants and preschool division, which produced $2.2 billion in revenues in 2012, two franchises stand as potential Barbie replacements: American Girl and Monster High.

Monster High is a high school populated by Goth chicks—imagine a mash-up of a Barbie doll with Elvira. The spark for the dolls came when a group of Mattel creative executives took a ï¬eld trip to Santa Monica’s shopping district with a bunch of tween girls. They noticed that the girls gravitated to a darker look and ruffled clothes of grays and blacks. “We got talking to girls from 6 to 10 years old,” says Stockton. “They begin to start thinking about what it’s like to be in middle school or in high school and all the social things that are fun and some of the social things that are a little stressful… They start to think about flaws. My hair’s too curly or my hair’s too long... Monsters are basically a personiï¬cation of human flaws, right?”

All those flaws add up: Monster High is expected to sell more than $1 billion at retail this year, producing an estimated $550 million in revenues for Mattel.

Mattel’s other golden goose is American Girl, a catalogue retailer of $110 dolls, which the company bought in 1998 for $700 million and has transformed into a retailing phenomenon. Its posh, company-owned American Girl stores are as close as you can get to Apple Store proï¬tability in the toy-selling business. The average American Girl store generates an estimated $1,500 in retail sales per square foot compared to about $320 at Build-A-Bear and just $240 at Toys “R” Us. American Girl’s well-made and wholesome-storied dolls have the highest gross margins at Mattel, at about 65 percent versus 63 percent for Barbie.

“Going to those stores is not, ‘Oh, let’s go down to Toys “R” Us and pick up a doll,’” says Sean McGowan of investment ï¬rm Needham & Co. “It’s a parade of revenue opportunities. Picking a matching outï¬t with your doll or getting a doll haircut. It’s like going to a show. It’s as much about the doll as it is a special time with mom.”There are already 14 American Girl stores in the US, and more are planned. Sales are expected to hit $600 million in 2013, up from $568 million in 2012, and Stockton recently tapped Jean McKenzie, former education chief for Disney and onetime Barbie manager, to run the growing franchise.

If Mattel has a glaring weakness, it is its dismal record with technology. In 1999, it spent $3.5 billion to buy educational software maker Learning Company (remember “Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?”), but almost immediately the operation began haemorrhaging cash to the tune of $1 million a day. Mattel dumped it a year later and has only reaped $27 million from the sale.

More recently, Mattel launched an Apptivity series of iPad games designed to let kids control the games with their plastic toys. It’s a daft concept and is predictably struggling. The Apptivity Monster High iPad game has already been abandoned. Likewise for Apptivity Hot Wheels. “We learned that we did better when we applied technology to traditional play patterns. Just being digital is not an end unto itself,” says Stockton. “The core buyer remains younger, and for them toy play has remained largely unchanged at about 30 minutes a day, even with the growth of digital.”

Stockton is gambling on the fact that Mattel can continue to create compelling new toys for this younger crowd, and given that for the last half-century his company has built a multibillion-dollar-a-year franchise on the slender ankles of a $10 plastic doll, it might not be wise to bet against him.

First Published: May 11, 2013, 06:49

Subscribe Now