UPI 2.0, BHIM and the new shape of payments

UPI's success is proof that India is moving mountains to usher in a less-cash economy. But the scope of BHIM must be widened

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur When former governor of Reserve Bank of India Raghuram Rajan, in April 2016, launched the Unified Payments Interface (UPI)—which allows instant, seamless fund transfer between bank accounts using a smartphone—there were many sceptics. New-age, technology-led government programmes had rarely worked before and a mass behavioural shift from cash to cashless was unheard of.Over two years hence, the sceptics stand corrected. Statistics suggest that UPI has been a game-changer. Official data from the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI)—the umbrella organisation for all retail payments in India that also operates the UPI platform—reveals a massive jump in usage and volumes.

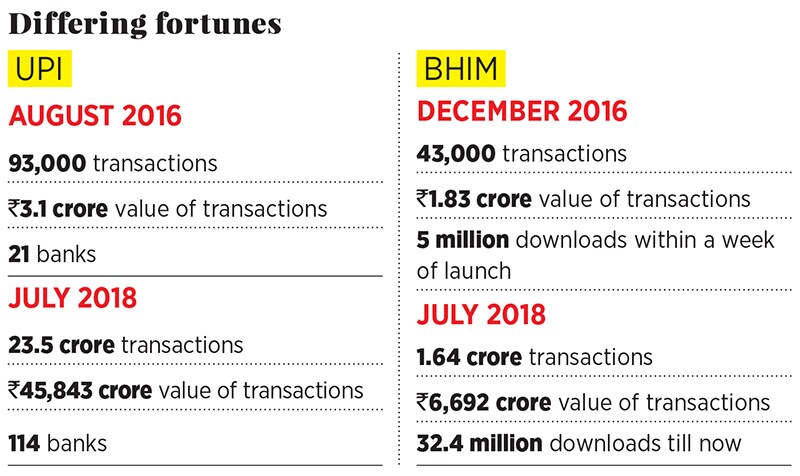

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur When former governor of Reserve Bank of India Raghuram Rajan, in April 2016, launched the Unified Payments Interface (UPI)—which allows instant, seamless fund transfer between bank accounts using a smartphone—there were many sceptics. New-age, technology-led government programmes had rarely worked before and a mass behavioural shift from cash to cashless was unheard of.Over two years hence, the sceptics stand corrected. Statistics suggest that UPI has been a game-changer. Official data from the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI)—the umbrella organisation for all retail payments in India that also operates the UPI platform—reveals a massive jump in usage and volumes.  In August 2016, around 93,000 UPI transactions (cumulatively valued at ₹3.1 crore) took place through 21 banks. This, in July 2018, multiplied manifold to 23.5 crore transactions (valued at ₹45,843 crore) through 114 banks. The shift towards UPI gathered pace post-demonetisation, when there was a scarcity of cash in the market.

In August 2016, around 93,000 UPI transactions (cumulatively valued at ₹3.1 crore) took place through 21 banks. This, in July 2018, multiplied manifold to 23.5 crore transactions (valued at ₹45,843 crore) through 114 banks. The shift towards UPI gathered pace post-demonetisation, when there was a scarcity of cash in the market.

“UPI set out to make payments safer and quicker, which it has done. Prior to this, though there were organised payment interfaces such as NEFT and RTGS and the debit card-based RuPay, India was not solving the problem of enabling real-time, 24X7 payments for the masses, for individuals and merchants," says Ramaswamy Venkatachalam, managing director (India/South Asia) at FIS, a global provider of financial services technology.

A newer version of UPI—in August, UPI 2.0 was launched—might fare even better. Currently, 11 banks including State Bank of India, HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank use UPI 2.0.

Some of NPCI’s other high-profile products are also successes: Notably, RuPay launched in 2012, which is challenging the duopoly of Visa and Mastercard in the payments gateway space.

While accurate data on market share is not available, according to NPCI there are close to 50 crore RuPay-powered debit cards in India, which translates to a market share of over 50 percent. (As of June 2018, there were 94.4 crore debit cards in India, according to RBI). RuPay has also started to power credit card transactions and some of its known advantages—lower transaction costs compared to Mastercard and Visa, no integration costs for banks and lower data storage costs—will likely emerge as game changers here as well.

RuPay has also started to power credit card transactions and some of its known advantages—lower transaction costs compared to Mastercard and Visa, no integration costs for banks and lower data storage costs—will likely emerge as game changers here as well.

One NPCI product where there is still scope for improvement is the Immediate Payment Service (IMPS). The instant, inter-bank, electronic fund transfer system, over which the original UPI platform was built, still requires a certain degree of digital literacy to use and is not yet seamless. Venkatachalam says that UPI is the “refined and finished" product of IMPS and he forecasts that at some stage, it could get merged with the NEFT system, operated under RBI guidelines. NPCI officials declined to speak to Forbes India for this article.

One other key product to emerge from the NPCI basket is BHIM (Bharat Interface for Money), the mobile app built on the UPI system. While growth for BHIM in terms of transactions has been strong, there are some concerns that need to be addressed.

BHIM transactions have risen to 1.64 crore (valued at ₹6,692 crore) in July 2018, from 43,000 transactions (valued at ₹1.83 crore) in December 2016 when it was launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi a month after demonetisation was announced. “Right now, business happens by way of [currency] notes and coins," the PM remarked. “That day is not far when all business transactions will be conducted through the BHIM app."

The app, developed on the UPI platform, is not an e-wallet but offers payment solutions by accessing bank accounts. It is linked to over 95 private and public sector banks. Within a week of BHIM’s launch, the app had been dowloaded more than 5 million times, without even an iOS version. Since then, BHIM has garnered over 30.88 million downloads on Android, and 1.54 million downloads on iOS.

Despite the initial burst of usage, BHIM seems to have lost its way even as India’s fintech industry has been clocking some phenomenal growth. This surge has been particularly led by companies such as Google (with its Tez payment system), Paytm and PhonePe. The latter, for instance, claims it has facilitated over 100 million transactions, while Paytm has over 94 million to its credit.

According to the NPCI, which runs the BHIM app, its share of all UPI transactions in July 2018 stood at a mere 14.5 percent.

The data showed that ₹6,692 crore was transferred through the BHIM app, of the ₹45,845 crore pie. This is a steep fall from around 42 percent of UPI transactions in September 2017.

“But then, BHIM wasn’t quite planned as an app that would rival the others," says a person who worked closely on building the app, declining to be named. “We were told to develop an app within three weeks, as a stop-gap solution to improve the cash flow following demonetisation. It served that purpose."

“BHIM was essentially created as a reference solution," says Sharad Sharma, co-founder Indian Software Product Industry Roundtable (iSPIRIT), a think tank that promotes the growth of Indian software product companies. “Over time, while it is serving its purpose, others have been aggressively offering cash back and better marketing, helping them grow in numbers."

BHIM’s diminishing fortunes also have much to do with a slew of offers that private mobile payments providers offer. With Paytm, for instance, users can pay bills, buy movie tickets, pay school fees or buy digital gold, apart from shopping on Paytm Mall.

Also, from July 1, the government, in a surprise move, announced the withdrawal of some of the incentives offered to BHIM users. It said that only new users would get incentives in terms of cashback. Also, these users will need to make at least 10 unique transactions of ₹50 each, to avail a cashback of ₹150.

“BHIM should add more categories to the payment application for user engagement," says Himanshu Pujara, managing director at the consulting firm, Euronet Services India. “To begin with, BHIM can be made mandatory for all payments to government-owned utilities. It can be made the default aggregator for all government-owned utility companies."

Some would argue that BHIM has been successful in creating a competitive ecosystem where players such as Paytm and SBI Yono operate, alongside Google Tez and others. “It was a catalyst intervention. But was it supposed to be a competitor for Paytm? It is ridiculous to think that," says a financial technology consultant, declining to be named.

The coming quarters will have to be watched very carefully, to see if more features need to be added to BHIM, to make it more viable.

First Published: Sep 03, 2018, 11:34

Subscribe Now