Family kitchens: Building a lasting legacy

For some of India's oldest family-run restaurant chains, business is an oscillation between leaving legacy untouched and reinventing to stay relevant

Hemamalini Maiya (centre) of Mavalli Tiffin Rooms with brothers and business partners Arvind (left) and Vikram

Hemamalini Maiya (centre) of Mavalli Tiffin Rooms with brothers and business partners Arvind (left) and Vikram

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Shivanna Sadanand first went to the Mavalli Tiffin Rooms (MTR) in Bengaluru 50 years ago, and has been a regular ever since. A lot changed in his life over time: He took a voluntary retirement from being the private secretary to former Congress minister HM Channabasappa, joined his family business of iron and steel raised, educated and married off his two children. But even today, the 78-year-old dutifully spends his Friday evenings and Sunday mornings at MTR, catching up with friends, discussing life, politics, literature, and everything under the sun. Back in the day, he recalls, the group was even joined by prominent Kannada literary icons like Masti Venkatesha Iyengar and Shivaram Karanth.

Bengaluru’s food and beverage (F&B) scene has changed as well. Many restaurants have emerged in the vicinity of the historic Lalbagh Botanical Garden where MTR’s oldest outlet is located. India’s IT city has emerged as the country’s pub capital, with eateries flaunting a multitude of global cuisine options for its well-travelled customers. But nothing’s changed at MTR, believes Sadanand. “Even today, the masala dosa, made with dollops of ghee, tastes the same as it did in the ’70s. So does the filter coffee. Badam halwa continues to be served every Saturday, and the chandrahara on Sundays, which is deep-fried maida flour topped with sweet liquid made from khoa,” he says.

Sadanand recollects getting to know MTR’s affable second-generation owner Harishchandra Maiya, who took over the business from his uncle Yajnanarayana Maiya. The latter was a cook from South Canara who founded the restaurant in 1924. Sadanand also remembers being uncertain about MTR’s future when Harishchandra’s daughter Hemamalini took over in 1999 after her father passed away following a prolonged illness. “Today, she has not only managed to run the Lalbagh Road outlet, but has also launched many others without ever changing the original MTR experience,” he says.This “spirit of MTR” is always at the core of every decision she takes, Hemamalini Maiya tells Forbes India. Along with brothers and fellow business partners Vikram and Arvind, she has taken MTR to eight other locations in Bengaluru, apart from outlets in Udupi, Singapore, Dubai and Malaysia.

The restaurant also has countrywide brand recognition because of the eponymous MTR Foods (owned and managed by Norwegian conglomerate Orkla) that sells processed and packaged food products like breakfast mixes, ready-to-eat meals, spices and savouries. Apart from being co-brands, Hemamalini says, the two entities do not affect the other’s business. Uncle Sadananda Maiya, who managed MTR with her father, split from the restaurant business in 1994 to take over MTR Foods. It was sold to Orkla in 2007.

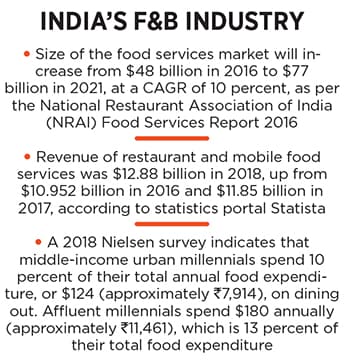

Like MTR, India’s hospitality industry landscape is dotted with age-old family-run restaurant chains, many inching close to a century or older. They are finding presence in cities and countries other than the ones in which they were launched, with third or fourth generation family members revving up expansion and chasing scalability through family-owned or franchise outlets. Across these brands, however, the overarching golden rule seems to be the same: Keep refreshing to survive competition, without letting go of the brand’s legacy. And each of these restaurant chains strikes that balance in its own way.  Bhagat Tarachand owners (seated L-R) Hitesh Gurmukh Chawla and Prakash Khemchand Chawla, and (standing L-R) Bhisham Ramesh Chawla and Saggor Ramesh Chawla

Bhagat Tarachand owners (seated L-R) Hitesh Gurmukh Chawla and Prakash Khemchand Chawla, and (standing L-R) Bhisham Ramesh Chawla and Saggor Ramesh Chawla

Image: Aditi Tailang

Same but Different

Take the case of Mumbai-headquartered Kailash Parbat and Bhagat Tarachand, or Delhi-headquartered Moti Mahal. All three were small restaurants started by refugees from Pakistan who settled in India after Partition. They expanded just to an outlet or two (or three) until the second generation. As the third generation took over, the brand remained the same, yet different.

“My goal was to launch 100 Moti Mahal outlets across the world before the restaurant turned 100,” says Monish Gujral. His grandfather Kundan Lal Gujral (who is seemingly credited with the invention of tandoori chicken and butter chicken) founded Moti Mahal in the 1920s in Chakwal, Pakistan, before relaunching in Delhi post-Partition. Soon, his tandoori cuisine found regular patrons in leaders like Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, former Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto, and former US Presidents Richard Nixon and John F Kennedy. Today, the restaurant is two years short of turning 100, but Gujral has already reached his goal.

Moti Mahal (renamed as Moti Mahal Delux during a brand upgradation in the 1970s by second-generation owner and Monish’s father Nand Lal Gujral) is now present in 18 Indian states, apart from outlets in Oman, Tanzania, Saudi Arabia and New Zealand. Over the years, more than 20 new dishes have been added to the original menu.  Monish Gujral is the custodian of the Moti Mahal brand.

Monish Gujral is the custodian of the Moti Mahal brand.

Image: Amit VermaWith a single-minded focus on expansion, the company opens between eight and 12 franchise outlets per year, with an average annual growth rate of 10 percent. Gujral believes in experimenting with restaurant formats, and invests between ₹40 lakh and ₹60 lakh in each franchised fine dining space and ₹10 to ₹15 lakh for the kiosk model. The models take two and one year respectively to break-even.

“We have nine models for the brand,” says Gujral, explaining that formats are tweaked depending upon the demand and the demographic. For instance, the Moti Mahal Tandoori Trail is a franchise option offering specialty cuisine in metros, while smaller cities in Punjab, Haryana, and Jharkhand (like Karnal, Panipat and Deoghar, for example) have multi-cuisine outlets serving Indian, continental, Chinese and Mexican food.

“People in smaller cities or towns prefer to step out as a family, and considering the lack of food options there, multi-cuisine restaurants work better than specialty outlets,” says Gujral, who has also leveraged Moti Mahal’s legacy to experiment with the quick service restaurant (QSR) format in shopping malls. “The food court models include sub-formats that specifically serve either tandoors, kebabs, chaat, Chinese, Mexican or Continental food.” These offerings are removed from what Moti Mahal originally stood for, admits the restaurateur who is also a chef. “But it is important to keep changing with time to keep the legacy alive.”

Kamlesh Mulchandani concurs with Gujral. When the third generation owner of Kailash Parbat took over in 2004, the restaurant had just three outlets, all in Mumbai. Fifteen years on, they have 52, out of which 35 are in India and the rest across countries like Singapore, the US, Australia, Canada, Qatar, China, United Kingdom and Thailand.

The menu has also been reinvented over the years. From simple pani puris, dahi wadas, kulfi faloodas and lassi, the restaurants now offer dishes like pav bhaji and Amritsari chole fondues, nachos, chipotle palak chaat, KP Long Island Iced Tea made with pani puri water, and jeera whiskey sour that contains a hint of ajwain.  The Mulchandanis of Kailash Parbat, (from left) Ramchand, Manohar, Jai and Kamlesh

The Mulchandanis of Kailash Parbat, (from left) Ramchand, Manohar, Jai and Kamlesh

Image: Mexy XavierIn Portugal, Mulchandani is now launching Kailash Parbat alongside another brand ‘Veganpati’ in an attempt to attract the emerging global vegan market. Here, one would find khichdi-flavoured risottos, burgers made with beetroot bread and sambar made with olive oil. According to Mulchandani, moving away from the core of what his restaurant conventionally stands for channelises growth beyond boundaries.

“This way, we remain Indian in terms of our offerings, but cater to an international customer base. In this competitive market, we have to constantly be on our toes, keep an eye out for the market and grow according to what does well,” says Mulchandani, who runs Kailash Parbat along with brothers Amit and Jai. “Today, we see a year-on-year growth between 15 percent and 18 percent. When a brand comes attached with a lot of expectations, it is our responsibility to do whatever it takes to keep it successful.”

Gujral, on his part, plans to look inward. He wants to take the Moti Mahal brand to small towns in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand like Hardoi, Rudrapur, Sitapur and Sultanpur. “These are aspirational markets. I plan to convert already-existing family operations that need professional intervention to Moti Mahal outlets. This way, the brand will reach the farthest corners of the country, with lower overheads and investment. It will also provide employment opportunities in rural areas.”

Old is Gold

Other restaurant chains are either inviting franchises cautiously, or not at all. Bhagat Tarachand, a chain known for its Sindhi-Punjabi cuisine, has only two franchises in the 124 years of its existence. The restaurant name is prefixed with one of four different letters (B,K,R or G), the alphabets denoting ventures owned by different third-generation family members.

All prefixes combined, Bhagat Tarachand has about 26 outlets across India, with one each in Mumbai and Bengaluru being franchises. Though descendants of founder Tarachand Chawla might have officially launched different outlets today, they function as one big unit. Interestingly, the founder, who started out with a box-sized stall in Karachi, earned the title ‘Bhagat’ (meaning kind) among the local people because he often let them eat for free if they could not afford a meal.

“We have decided against indiscriminate expansion in order to maintain strict quality control processes,” says third-generation owner Prakash Khemchand Chawla, who runs B Bhagat Tarachand.

“For example, our Basmati rice comes from the foothills of the Himalayas, our onions from Nashik and our chillies from Kashmir. We have specialised vendors for every ingredient.”

Of late, 11 fourth-generation family members have also joined the business. They intend to continue on the broad expansion plans laid out by their predecessors. This includes strategies like identifying locations around busy marketplaces, or residential areas with a sizeable Gujarati or Marwari population, and working on the QSR model, explains Hitesh Gurmukh Chawla, fourth-generation member who manages B Bhagat Tarachand.

“We have grown up watching our fathers, uncles and grandfather be so hands-on in the business. They used to cook rotis on coal stoves, carry heavy sacks on their backs and offer home-like food at an affordable price point,” says Saggor Ramesh Chawla, a fourth-generation member from the K Bhagat Tarachand outlet. “Today, we have various conveniences and mechanisations that make our jobs easier. But even if we become social media savvy or modernise our plating and food presentation, at the core, we want to remain just the same.” Priya Paul (left) of Flurys with mother Shirin

Priya Paul (left) of Flurys with mother Shirin

Image: Amit VermaSimilar business philosophies are followed by restaurants like Flurys and MTR. Priya Paul is the chairperson of the Apeejay Surrendra Park Hotels, who also owns the iconic Flurys. Instead of giving out franchises, she has experimented with various formats to expand the confectionary outlet across and outside of Kolkata. These formats include fine dining tea rooms, standalone kiosks or counters with just a couple of tables.

Flurys, an iconic tea room located on 18 Park Street, Kolkata, was founded in 1927 by a Swiss expatriate J Flurys and his wife. The Apeejay Surrendra Group acquired it in 1965. It is popular for its English breakfast menu, apart from cakes and creamy pastries. “We experiment with restaurant formats because everyone in Kolkata knows Flurys, and across the rest of India too, there is a certain nostalgia associated with the brand. So we have had to identify a model that works best in each city, and do things differently from other confectionaries,” Paul says.

In the first phase of rollouts, a Flurys outlets was opened alongside The Park hotel property in Delhi, apart from 24 outlets across Kolkata and one in Mumbai. The three-year compound annual growth rate for Flurys has been 31 percent, with the brand’s ecommerce website (that delivers to select cities across India)and presence on online food delivery platforms contributing 5 percent of total sales. Now, Paul plans to launch the second phase of rollouts, which will involve setting up a base kitchen in Delhi at an investment of about ₹25 crore. “The base kitchen will be set up by mid-2019, after which we plan to add 60 Flurys outlets in the Delhi-NCR region in the next three years.”

Hemamalini Maiya of MTR also has similar reservations about franchising. So particular is the brand about quality control that it only sends chefs trained at its restaurant in Bengaluru to work in international outlets. She says that one of the main reasons they did not take up opportunities to expand in Australia, England and the US is because those countries did not allow their cooks from Bengaluru to work there. The culinary enterprise has also seen interest among private equity investors, but the promoters have not gone down that road yet.

“This is a business started by our ancestors. For us, its identity is more than just a brand. Even today, we promoters spend a lot of time in the kitchens, talking to chefs, encouraging them, correcting their errors, appreciating them and also giving them emotional support when required,” she says. “Every employee in every outlet must get into the skin of the brand and its legacy. That is why we are not in a hurry to expand, but are happy growing one restaurant at a time.”

First Published: Feb 22, 2019, 11:51

Subscribe Now