Venture capital's next focus: India's edtech ecosystem

Venture capital funds are pouring in for edtech startups that are looking to bridge the learning gap for the next half billion

Image: Sameer Pawar[br]Deepanshu Arora initially bootstrapped his venture of building a cloud-based teacher collaboration software. When recently he started to look to raise funds, he wasn’t sure there would be interest from venture capital (VC) firms. But, as it turned out, he caught the attention of a well-known mainstream VC firm, Matrix Partners. In January, Matrix invested an undisclosed amount in Arora’s Teacher Tools Private Limited: Toddle, the collaboration software, is now used by 12,500 teachers in 530 schools around the world and counting.

Image: Sameer Pawar[br]Deepanshu Arora initially bootstrapped his venture of building a cloud-based teacher collaboration software. When recently he started to look to raise funds, he wasn’t sure there would be interest from venture capital (VC) firms. But, as it turned out, he caught the attention of a well-known mainstream VC firm, Matrix Partners. In January, Matrix invested an undisclosed amount in Arora’s Teacher Tools Private Limited: Toddle, the collaboration software, is now used by 12,500 teachers in 530 schools around the world and counting.

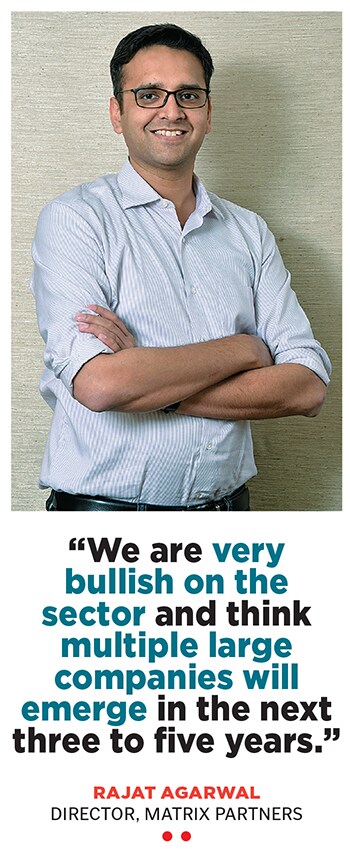

For Matrix, this was only the latest in a succession of edtech investments in recent times. Says Rajat Agarwal, a director at Matrix Partners, “The last 12 to 18 months have seen unprecedented company creation as well as investor interest in the edtech space. In fact, Matrix India has invested in six edtech companies in the last 12 months.”

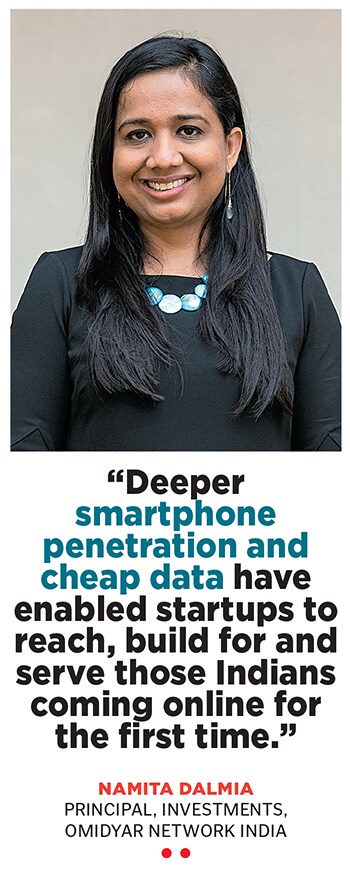

Not just Matrix, Omidyar Network India, too, has been eyeing the sector. Last September, it was among the investors who put $10 million into White Hat Jr’s series A funding. The startup helps children between six and 14 years build commercial-ready games, animations and apps online using the fundamentals of coding. “Deeper smartphone penetration and the availability of cheap data has enabled startups to reach, build for and serve the next half billion Indians coming online for the first time via mobile phones,” says Namita Dalmia, principal, investments at Omidyar Network India. “With companies now building for the next half billion, we are at the cusp of this industry growing rapidly.”

Agarwal points to three factors that are bringing edtech startups and VC firms together: First, enabling infrastructure such as high speed mobile internet, seamless and widespread digital payments and financing have all come together over the last 18 to 24 months second, the improved quality of entrepreneurial talent entering the education market and third, several examples of successful edtech companies in China and even in India making founders and investors confident that the opportunity is real.

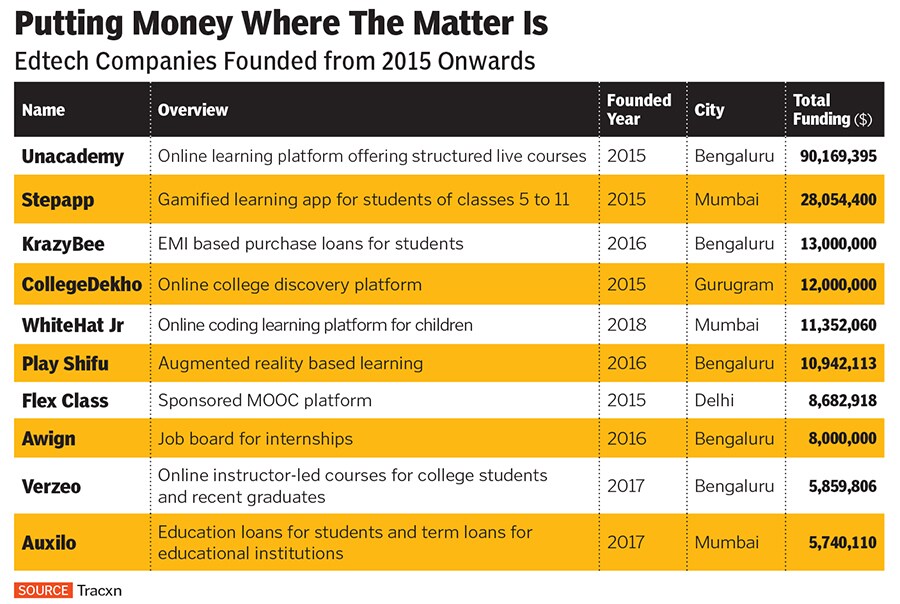

Besides, most edtech startups have now begun to build genuinely unit-economics-positive models. Sajith Pai, a senior member of the investment team at Blume Ventures says Unacademy is an example of an edtech firm that has seen “incredible” revenue growth. Unacademy has built an online site for learners to find experts in subjects and courses of their interest. The venture raised its series D funding of $50 million last June with investors including Steadview Capital, Sequoia India, Nexus Venture Partners and Blume.The entry of entrepreneurs with experiences in large tech ventures has spurred the growth of the sector even further. Pai says, echoing Matrix’s Agarwal, that because today’s founders are often those who have already done something entrepreneurial or have spent years in the bigger ventures that came up in the first wave, such as Flipkart, it has raised the level of entrepreneurship in the sector. For instance, Toddle’s Arora already had experience running pre-schools of his own, and the first software he built came out of his own need for something better than what he could find in the market.

Pai talks of having discussed a venture with one of the earliest tech employees at Flipkart and finding that he had both the “unicorn experience” and the “Esop money” to chase his own passion. “This is generation two of founders. They don’t make the same mistakes,” Pai says, which is something always attractive to VC firms. In parallel, the more successful of the first-generation founders have also turned angel investors and mentors.

Matrix’s investment thesis has not changed much over the years. However, entrepreneurs have matured and are thinking harder about how to acquire customers at low costs and how to build sustainable businesses with high gross margins and high customer-life-time value. Similarly for Omidyar, Dalmia adds that the entrepreneurs the firm is investing in are able to show high customer satisfaction measured through the net promoter score (NPS)—a measure of how many users are saying good things about a product or service—and deep engagement on one hand, and monetisation, efficiency and high renewal rates on the other. For example, a startup like Vedantu—another Omidyar investee—is able to link student success in examinations such as IIT-JEE to their pioneering live teaching model, proving it works as effectively as or better than the incumbent offline models. So, students and their parents now have the option to substitute supplemental coaching classes with an online-only alternative. The goal is to help create meaningful lives rather than adding any further burden in this space, she says.

The edtech space has both companies that are targeting the Indian market and those that are developing products for the overseas market. For example, from Matrix’s portfolio, Toddle, Pesto and another unnamed early-childhood learning company are building global companies from India, whereas Testbook, a preparation portal for government job aspirants, and two other unannounced investee ventures are targeting the after-school learning market within the country.Edtech companies are also coming up in a variety of areas—some, like training young graduates for government job entrance tests are relatively niche, while others are building their ventures around tutoring and helping students online and outside their school ecosystem. But, for Dalmia at Omidyar Network, education has a socio-cultural context and most, if not all, Indian edtech companies are looking at India as their core market and building their product for the large potential here. A few companies in the workforce-development or coding-for-kids space that are focussed on India also have the potential of expanding to the overseas market and being competitive on both fronts.

Here’s an example: Last October, entrepreneurs Raj Desai, Varsha Bhambhani and Pratik Agarwal raised $300,000 in seed money for their School of Accelerated Learning that aims to upskill young engineering graduates. For Astarc Ventures, which led the funding, this was their first foray into edtech. “There is an acute shortage of supply with respect to tech talent in the market and with the tech stacks evolving rapidly, an effective upskilling solution with the focus on the industry is the key to bridge the gap,” Salil Musale, director at Astarc says.The willingness to spend large parts of the household income on better quality of education has always existed in India. However, quality education has neither been easily available nor affordable for large parts of the country. “We are beginning to see companies address this gap and, in a few cases, in a profitable way as well. Hence we are very bullish on the sector and think multiple large companies will emerge in the next three to five years. Edtech in India is at an inflection point,” says Agarwal of Matrix.

A large addressable population with differentiated needs across city tiers, income groups, languages and curricular needs present the opportunity for continued disruption and has room for multiple edtech winners, says Dalmia. Omidyar’s research shows that there is an increasing awareness about edtech among those with internet access, as well as a growing willingness to pay for these services. Over the next five years, both these metrics will only grow. This outlook combined with the demonstrated impact thus far will ensure that the funding ecosystem will continue to back innovations at both early as well as growth stages, she adds.

While there are multiple interesting areas, the largest opportunity for edtech startups in India continues to be in the after-school learning across different age groups. The number of students that will use online learning platforms is expected to grow 10x over the next five years, Agarwal says. There will be multiple companies that will successfully go after this space with different go-to-market strategies and customer segments.

The high net promoter score in this category compared to other digital categories has demonstrated that good products are able to create value for consumers while also making it possible to monetise the platform, Dalmia says. Startups today have an opportunity to demonstrate that their products can lead to outcomes whether it is related to school exams, college admissions or jobs in order to strengthen trust and become the primary source for learning, she says.

As to challenges, while things are moving in the right direction, not all edtech companies have proven unit economics or demonstrated significant improvement in learning outcomes at scale, Agarwal says. Dalmia adds that a challenge that remains is doing business directly with either government or affordable private schools to help change the way learning happens inside schools.

First Published: Feb 18, 2020, 15:32

Subscribe Now