The road to Snapdeal 2.0

How the virtual marketplace is building a self-sustaining ecosystem to overtake Flipkart as market leader

It was February 2013. Winter was finally bidding farewell to Delhi. But for Kunal Bahl and Rohit Bansal, founders of online retail company Snapdeal, spring was nowhere in sight. The duo was staring at an uncertain future with only $100,000 in the bank and were looking at paying salaries of $1 million. One of India’s homegrown virtual marketplaces could all but hear its death knell.

The founders spent long hours discussing ways to tide over the crisis. Winding up the business was also considered. Two options were laid out at a meeting of the company’s top executives: Cut back on expenses or sack employees. “It was an intense time for everyone in the organisation,” says Bansal. In the end, it was an easy choice. “The decision was unanimous. We would not lay off a single person. Our business has no plant and machinery we are a people-centric business.”

Fortunately, salaries weren’t delayed thanks to a timely venture debt of $1.5 million from SVB India Finance (since renamed InnoVen Capital), a subsidiary of Silicon Valley Bank. But while pink slips were not handed out, survival continued to remain top priority. “We knew that there would be a day when we would come out of this. But we wanted to come out as a strong team and not an impaired company,” says Bansal, 32, also the COO. The pressure was palpable at Snapdeal’s Okhla office. “Expenses towards electricity, water, marketing were cut down… we paid attention to each and every thing. It was a very stressful time for Kunal [co-founder and CEO] and I because so many people’s lives were dependent on us.”

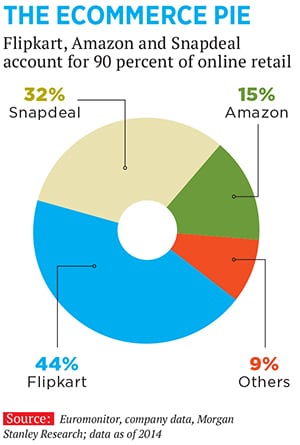

Cut to today. Snapdeal’s new Gurgaon office, set up in August 2015, is buzzing with activity. The company has been aggressively making talent acquisitions, hiring over 20 senior management executives in the last year alone. It occupies a major chunk of the etail market today—32 percent according to a Morgan Stanley report. Ever since SoftBank Group Corp came in as investor in October 2014 bringing in $647 million in fresh capital, Snapdeal has acquired six businesses and snapped up majority stakes in two others. “We are very well-funded for the next couple of years,” says Bansal. It has also lured some top executives from across sectors to join its leadership team, some of whom have even relocated from the Silicon Valley in the US.

“It has been a fantastically impactful journey and an intellectually rewarding one,” says the 32-year-old Bahl. “But it has not been without its challenges. We easily have many more challenging days than rewarding ones.”

But there is no challenge bigger than the one ahead: Not only does Snapdeal have to become a one-stop shop for its consumers, it also has to build a self-sustaining ecosystem for itself—one that accommodates new-fangled business models, profitability and growth goals, innovation, etc. All this even as homegrown rival Flipkart steams ahead of it, and global giant Amazon breathes down its neck.

Think Snapdeal 2.0.

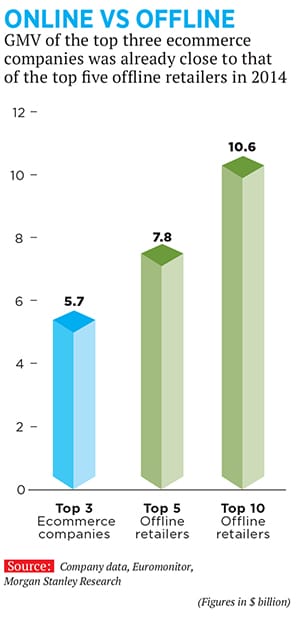

And the company seems to be on its way. From getting into a payments platform through its acquisition of FreeCharge and setting up offline platforms that bridge the gap between virtual stores and brick and mortar ones, Snapdeal has taken a few steps in the right direction in the last year and a half. “We changed our model six times to get here. And we are still pivoting and evolving. If companies don’t evolve, they will die,” says Bahl. Today, Snapdeal has over 200,000 sellers on its platform compared to only 1,000 at the end of 2012. According to a February 2015 report by Morgan Stanley titled, ‘The Next India: Internet—Opening Up New Opportunities’, Snapdeal ranks second occupying 32 percent of the ecommerce pie, next to market leader Flipkart at 44 percent. Amazon India is third with 15 percent. Snapdeal 2.0 hopes to bridge that gap.

Today, Snapdeal has over 200,000 sellers on its platform compared to only 1,000 at the end of 2012. According to a February 2015 report by Morgan Stanley titled, ‘The Next India: Internet—Opening Up New Opportunities’, Snapdeal ranks second occupying 32 percent of the ecommerce pie, next to market leader Flipkart at 44 percent. Amazon India is third with 15 percent. Snapdeal 2.0 hopes to bridge that gap.

School pals from Delhi Public School, RK Puram, Bahl and Bansal had often toyed with the idea of starting a business. Hailing from business families, it ran in their genes. After completing his MTech from IIT Delhi, Bansal started working in the American bank holding company, Capital One, in New Delhi. Bahl, a Wharton graduate, had got a job with Microsoft in Seattle. Their casual chats took a serious turn when Bahl, on being denied an H1B visa to work in the US, came back to the country. The 22-year-olds started Jasper Infotech in 2007 with an aim to publish discount coupon booklets called MoneySaver, a booklet of coupons from various retailers. The cumbersome and inventory-heavy business failed. The duo managed to sell only three of the 50,000 booklets already printed. From physical, perishable coupon booklets to mobile coupons and discount cards, they tried their hand at it all and in January 2010 decided to sell their coupons online. A long chinwag over coffee on Republic Day ensued and eight days later Snapdeal.com, an online platform giving daily deals from local merchants such as restaurants, salons, spas, etc, was launched.

But it was the founders’ visit to China in November 2011 that marked the watershed moment. Chinese ecommerce giant Alibaba’s growth path impressed them and they left convinced that such a model catering to people’s real needs must be emulated in India. Recent lessons were kept in mind. “It took us a year to launch MoneySaver and within a week we realised that consumers did not want it. This is when we learnt how important it is to keep listening to your users,” says Bansal.

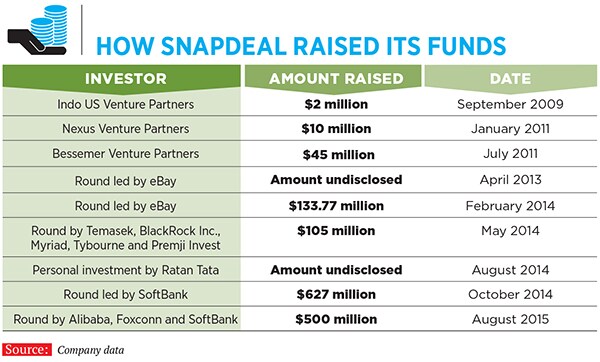

The company received its first round of funding of $2 million in September 2009 from Indo-US Venture Partners and $10 million in January 2011 from Nexus Venture Partners. “We chose Snapdeal because of the smarts and agility of the team. They had just pivoted from a corporate deals aggregation service to consumer deals online. They had strong marketplace DNA—deep insight on SME needs in India and what Indian consumers are seeking,” says Suvir Sujan, co-founder & MD, Nexus Venture Partners. In September 2011, Snapdeal transitioned into an online marketplace for products.

However, the going was never smooth. “Our journey has been far more jagged than that of most breakout tech companies in India,” says Bahl. “Most breakout companies started in the business that they are in. But we started as a company that published coupon books.” Money trickled in with every fresh round of funding but big money always eluded the company. “For a while, Snapdeal’s business model and focus was changing and they were also up against a well-funded competitor like Flipkart. So the incoming investor would have found the risk to be too high,” says Avnish Bajaj, managing partner, Matrix Partners.

After the founders took a loan from SVB to tide over the crisis of 2013, a bridge loan of $11 million had to be taken (in February 2014) from investors. Eventually the founders, even with financial constraints, efficiently moved towards building their online marketplace model. This got the investors comfortable.

But it was only after the eighth round of fundraising that the company finally developed muscle and had the freedom to call the shots.In July 2014, Bahl and Bansal met Masayoshi Son, founder and chief executive officer of SoftBank, in Tokyo. Son had evinced interest in Snapdeal a couple of times earlier but this time Snapdeal had to make the deal work if its ambitions were to be realised. The company had just crossed $1 billion in GMV (gross merchandise volume) in August 2014. Son had worked successfully with Alibaba’s Jack Ma and tracked the group’s growth for over 15 years. “Having identified the China market as a future growth leader over 15 years ago, Masa was convinced that India was going to be next,” says Nikesh Arora, president & chief operating officer of SoftBank Corp.

Coincidentally, Arora met Bahl during the latter’s trip to Tokyo. “Both Masa and I got excited about his progress so far, and were convinced that he and Rohit were definitely on their way to helping redefine commerce in India. With no real scale in organised retail, a young tech-savvy population, and the explosion in consumer growth, we felt India was ready. And Snapdeal was going to be our partner in the market,” says Arora.

In October 2014, SoftBank pumped in capital to the tune of $647 million, making it the company’s largest investor. (In August 2015, during the last round of fundraising, Snapdeal was valued at $5 billion according to reports at the time, Flipkart was valued at $15 billion). It also freed the company to break away from its financial shackles and play catch-up with the other ecommerce players. “The SoftBank investment moved us from being in a two-hands-and-two-feet-tied-but-let’s-run-really-fast’ [state],” says Bahl.

Son also set Snapdeal onto its future course and advised the founders to follow in Jack Ma’s footsteps. “He [Son] told us that eventually you have to build an ecosystem [and to] make sure that your core platform is strong and build long-term differentiated capabilities that will make your core platform strong,” says Bahl.

Keeping Alibaba and eBay as models, Snapdeal is aiming to create “a digital ecommerce ecosystem”, says Bansal. Last March, Snapdeal took a majority stake in RupeePower.com, a marketplace for financial services, for an undisclosed sum. This made Snapdeal India’s first ecommerce company to foray into financial services. The founders then turned their attention to building a payments platform.

Bahl and Kunal Shah, founder and chief executive officer at FreeCharge, an online recharge (for mobiles) company, had known each other for over six years. Their acquaintance went back to the time Bahl ran MoneySaver and Shah operated Paisaback, a business that helped offline organised retailers run cash back promotions. There was mutual respect as both had keenly tracked each other’s professional journeys and trials over the years. They met in little-known cafes to avoid drawing attention. Bengaluru’s Hotel Novotel and the lobby area of Mumbai’s Palladium Hotel were also preferred locations to discuss the future of ecommerce.

FreeCharge was not in distress. It was sitting pretty on over $95 million, having spent only a fraction of the total funds that they had raised so far. Ecommerce giants, including Flipkart, were also wooing it. But Snapdeal was a shoo-in, says Shah. “I have a lot of respect for entrepreneurs who had to make a comeback after they had to almost shut down the company or had to struggle for capital. It is a character-building thing,” says Shah.

Two weeks of discussion followed and the deal between Snapdeal and FreeCharge was closed within 21 days of signing the term sheet. In April, the announcement was made that Snapdeal had made one of the largest internet acquisitions in the country by buying FreeCharge for $400 million. The joint entity also meant a captive customer base of 40 million and Snapdeal’s access to younger customers aged between 18 and 25 years.

A combination of factors swung the deal in Snapdeal’s favour. “What convinced us was that combining the units multiplied growth. We could tap into existing customers rather than acquiring them,” says Shah. Snapdeal also allowed FreeCharge to remain a separate entity with Shah as CEO. “Indian ecommerce companies will realise in time [what] we realised 7-8 months ago when we acquired FreeCharge. If you look at eBay and PayPal, TaoBao and Alipay, ecommerce companies became successful as they were in association with a payments company and vice-versa,” says Bahl.

The ecosystem had started taking shape.

“Many ecommerce companies are changing their focus from valuations and growth to profitability as raising capital becomes difficult,” says Sandeep Ladda, partner and national leader of the technology and ecommerce sector, PwC India. Snapdeal is emphasising on profitability too. In a market that is still obsessed with GMV, Snapdeal has set ambitious targets to start making money. “If you start with GMV as a primary goal, there are many ways of reaching it. It can be the outcome of all that you are doing, rather than the starting point,” says Bansal. “We are very long term in our running of the business. What we care about is that in 10 years, are we as a company creating real value and impact for millions of people or not?”

Nonetheless, the company has performed impressively on GMV too, moving from $1 billion in August 2014 to $4 billion at the same point this year. Flipkart is only marginally ahead with $4.5 billion. “We want to get to a GMV that makes the company profitable in 3-5 years that number would be the $15 billion mark,” says Bahl.

Snapdeal’s focus on financial services and forays into newer business models has been noted by industry experts. “This is an inevitable evolution as there is great ease in doing business,” says Abhijit Joshi, founding partner, Veritas Legal, who helped seal the omni-channel deal between Snapdeal and Shoppers Stop.

The online marketplace has started an offline interface that will allow customers to browse and transact online but enjoy supporting services offline. Tie-ups with The Mobile Store and Michelin Tyres along with Shoppers Stop have been kicked off, and more collaborations are to follow.

Snapdeal’s Chief Technical Officer (CTO) Rajiv Mangla has termed the omni-channel platform ‘Janus’, after the two-headed Roman god. Says Bansal, “Even 10-20 years from today, the lion’s share of commerce in this country will be offline. But is there an opportunity to make life easier by making this entire process smoother? Yes. Hence, omni-channel made perfect sense to us.”

An Amazon India communications representative said the company has “no plans of getting into offline selling”. Flipkart, however, has followed in Snapdeal’s footsteps and ventured into offline selling, calling it “assisted ecommerce” and restricting it to mobile phones for the time being. Smaller etailers such as Lenskart, HealthKart, CaratLane and Pepperfry have also recently tried their hand at offline.

“It is one of our big regrets not to be invested in Snapdeal,” says Matrix Partners’ Bajaj. “Snapdeal has a history of experimenting with a multitude of business models. The reality of ecommerce is that it is a war of discounting and attrition, which can only be won by somebody who has most amount of capital. If you have to win the war, you have to do something different and Snapdeal is doing interesting things.”

With SoftBank having brought in more liquidity, Snapdeal has been quickly picking up companies through what the founders term as “planned aggression”. These acquisitions were being done with the aim of widening the Snapdeal umbrella, bringing in various verticals under it. The founders confess that they took the cue from global majors such as Facebook and Google, with the idea of presenting consumers with the focussed services that would be tailor-made for their whims and fancies.

“About a year ago, we started realising that the future of ecommerce is not a monolithic platform. Facebook started talking about a clan of apps and we realised that it would start happening in the world of ecommerce,” says Bahl. Other than RupeePower and FreeCharge, Snapdeal has taken over Wishpicker, a gifting recommendation firm Exclusively, a marketplace for luxury and premium products MartMobi, an m-commerce startup LetsGoMo Labs, a mobility solutions company and Silicon Valley-based adtech platform Reduce Data. Another key move was to get into a strategic partnership along with a minority stake at logistics firm, GoJavas. Snapdeal is in advanced stages of talks for three more acquisitions.

The company has been in acquisition mode on the people front too. More than a dozen top management executives have recently joined Snapdeal. “The quality of our team is the most important ingredient in our business. It is critical for us to have the best team in the country. Someone told us when we started out that one must always have people better than oneself,” says Bansal. Govind Rajan, formerly CEO of Airtel Money, has joined as COO, FreeCharge and CSO, Snapdeal Rajiv Mangla has joined as CTO of Snapdeal after a decade at Adobe and former Aircel CFO Anup Vikal has come on board in the same capacity. Talent from the Silicon Valley, Rahul Ganjoo and Gaurav Gupta, have both joined as VP (Technology). “Snapdeal was transforming lives through technology. But I was primarily impressed with the leadership,” says Ganjoo.

Silicon Valley veteran Anand Chandrasekaran, who has joined as chief product officer, remembers Bahl drawing a string of pearls on a hotel napkin, explaining the ecosystem they were striving to create. “My father was a small business owner and what Snapdeal can do for a small businessman has been a personal thing. I am very impressed with the kind of company that Rohit and Kunal are building,” says Chandrasekaran.

Over 1,000 engineers joined the company in the last year to ramp up technology and the backend. A Bangalore multimedia research group with 350 people has also been opened. “We are one ecosystem and, therefore, technologies have to come together. We have to make ourselves the most favoured destination for discovery and need to get to top-of-the-mind recall of users,” says CTO Mangla. Strengthening technology and logistics has helped the company reduce the error rate from 400 for every million orders to 10, and also bring down the average delivery time by 70 percent.

For expediting things further, they offer Snapdeal Plus as a service for sellers, where merchants with the help of newly-opened fulfilment centres can dispatch products faster while ensuring standardisation. Over the last 7-8 months, Snapdeal has built 63 such fulfilment centres spanning over 1.5 million square feet. The partnership with GoJavas has also borne fruit, slashing delivery time by 36 hours. “In the first 100 days of us investing in GoJavas, they opened in 150 cities. We were able to expand our footprint with them,” says Bansal. “We have a 90-minute pickup. A card-on-delivery service was launched in 150 cities. We have launched 4-hour deliveries too. There has been a massive improvement in customer experience and reduction in delivery time.” This comes on the back of the company investing $300 million into supply chain and logistics.

A strong backend resulted in euphoric results in their Diwali sale, the company says, adding that six million orders were shipped at the rate of 300 orders per second at peak hours. “Last year, I spent more than 70 percent of my time on the tech floor. This time I wasn’t even there for the first 1.5 days. I was out of the country,” smiles Bansal.

His confidence is reflected in the energy at Snapdeal’s new Gurgaon office that sprawls across 4.5 lakh square feet. Employees chat animatedly about the upcoming sale seasons. They know that it will be a tough few days but there is no dampening of the spirit. Should work get too stressful, the company is offering spa and salon services on the house. Snapdeal currently has over 7,000 employees, from under 500 employees in 2012. The women to men ratio stands at 40:60, quite promising for a tech firm, though there are no female executives in the boardroom yet.

Workers enjoy a game of pool or race cars on a PlayStation in the recreational area even as Bahl and Bansal pose for pictures. The founders share a few laughs, discuss a recent event that was attended by a supermodel and her techie beau. Their plans for the company are ambitious, they say.

There is no hint of stress, only a sharp glint in their eyes screaming determination. It is time to focus on new categories and selling platforms. And they have their hands full.

Snapdeal has launched Snapdeal Motors to sell bikes and cars with a GMV target of $2 billion by 2017. It has partnered with auto majors such as Mahindra, Hero Motocorp and Piaggio. “We noticed huge pent-up demand in the automobile category. We have sold around 300,000 bikes since the launch in partnership with Hero and others. Around 57 percent of all the users were first-time buyers,” says Tony Navin, a senior vice-president at Snapdeal.

The company is also rolling out its own advertising platform for sellers called Snapdeal Ads. This platform, which has been started in a phased manner, will aid in the discovery of products and boost sales through targeted advertising.

Snapdeal is also in the process of offering its mobile interface and website in 11 regional languages. It has launched Sherpalo, a platform built to enhance the seller experience and provide a single-window access to all seller services such as training and product listing.

Shopo, meanwhile, is an app-only, zero-commission-based marketplace to cater to individuals and small businesses that want to sell online on a small scale in a hassle-free manner. And the genesis of this idea came from another tech leader in India.

Rajan Anandan, VP and MD, Google, South-East Asia and India, had called Bahl asking where his nine-year-old daughter Maya could sell her handmade pendants. That got the founders thinking.

“We were rejecting 8 out of 10 sellers that came on board to sell on Snapdeal,” says Sandeep Komaravelly, senior vice president, Shopo. “This large percentage of sellers, who are medium to small, does not have a platform. That was the genesis.” Shopo was launched in July and in ten weeks crossed over a million listings. “And we haven’t even announced it yet,” laughs Bahl.

Snapdeal also claims to be fastidious about transparency. The company says it is a rare private entity that voluntarily conducts quarterly audits.

Much like Alibaba, Snapdeal, too, has plans of listing. “Rohit and I were clear that we wanted to take the company public in India where our buyers and sellers can become our shareholders eventually,” says Bahl.

It took Alibaba 16 years before its IPO. Snapdeal, with its expansive plans, hopes to cover it in half the time.

“We would be taking a serious look in three to five years,” says Bahl. “But before we get there, we want to get to the profitability profile because as a public company you want to offer predictability to shareholders.”

The destination is daunting but it is a journey that Snapdeal 2.0 seems well-prepared to take on.

First Published: Jan 06, 2016, 06:58

Subscribe Now