Why Venky's Need to Exit Blackburn Rovers FC

Its move to expand the Venky's brand in Europe by owning a football club has backfired. Now, fans want to own a sinking Blackburn Rovers

When the Pune-based Venkateshwara Hatcheries Group (VH Group), a seller of poultry products, bought Blackburn Rovers Football Club in November 2010 for £23 million, the club was a strong outfit in the English Premier League (EPL). Fans were optimistic that new investment would propel the club to European football championships and enable them to run for the domestic league title once again, much like Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich’s investment did to Chelsea in 2003.

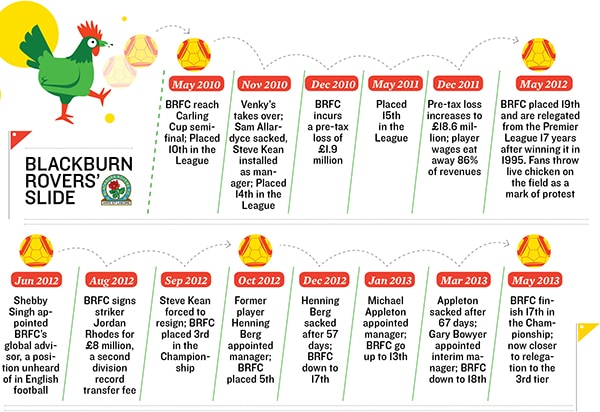

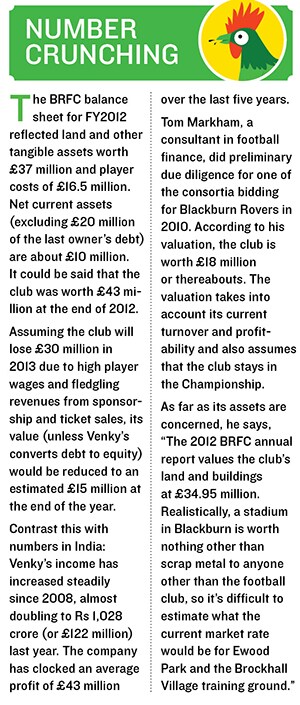

But it won’t be an exaggeration to say that VH Group’s (popularly known as Venky’s) ownership of Blackburn Rovers has been disastrous for both parties. While Venky’s has received bad press (voted by fans as the worst owners in the English league), the club was relegated to the second tier of English football (the Championship which lags the more glamorous EPL in terms of television viewership, sponsorship and revenues) in 2012. It has already seen five managerial changes, declining stadium attendance, and increasing financial losses. And its value has fallen more than 25 percent. In April, local fans acquired a minority stake in the club. And now, they plan to raise capital to turn that into a controlling stake.

WHAT WENT WRONG

Even though Blackburn Rovers, one of the five teams to win the Premier League since its inception in 1992, was a strong side, it was hard to spot the connection between a poultry business from India and a football club in northwest England.

Dan Grabko, finance officer at the Blackburn Rovers Supporters Trust (BRST), says, “The club is the lifeblood of the local and regional community and what has happened to it over the past 30 months is devastating to the area on socio-economic levels.” The club is the heartbeat of the former cotton mill town of Blackburn in Lancashire county. As a result of its relegation to the Championship, the club has lost an estimated £5 million as advertiser spending has fallen. The BRCT, which is a charitable organisation representing local fans, had its funding cut by more than half.

The club’s squad has been chopped. Many experienced Premier League players, some of them talented imports, have been replaced. And now, the team has only two marquee players, Jordan Rhodes and Danny Murphy, in the midst of cut-price youths, non-permanent loanees (players roped in for one season only) and those untried in the English game. Even the marquee players haven’t been a good buy for the club with Murphy well past his prime. “The signing of Danny Murphy for more than £30,000 a week, at the age of 34, is something no Championship club would do. If Venky’s had put experienced English football administrators in place or kept the highly respected ones they inherited, these mistakes would not have been made,” says Grabko.

OPERATIONAL WOES

It’s not that the club doesn’t have money—during FY2012, it made a trading profit of £17 million—it’s just that it has spent it poorly. Former manager Steve Kean revealed that many players had been signed on without consulting him. It was unclear who had roped them in. The club’s board has had three different

directors in the last 30 months. The instability is crippling. Grabko says, “What the club needs is an experienced and proven manager. This is the most important and cost-effective investment that could be made at this point in time.”

One of the most inexplicable appointments was that of Shebby Singh, former Malaysian footballer and TV pundit who was signed on as the club’s global advisor in June 2012. “Blackburn Rovers is the only professional football club in the UK that has a global advisor. Not Manchester United, not Chelsea or Liverpool. I think that speaks for itself,” says Grabko. Fans believe that no candidates were shortlisted and Singh landed the job through his connections with the Rao family (promoters of Venky’s).

Shebby Singh did not respond to Forbes India’s questions.

Kevin Rye, spokesman for Supporters Direct (Europe’s leading organisation within sport and community engagement), is of the opinion that Venky’s has neglected two vital elements to build a successful business: The internal set-up (or governance) and the relationships between key people. “You can’t hire and fire at will. Would it work in any other business? I doubt it. So why do it in football?”

Former manager Henning Berg, who was sacked in December last year, took the club to court claiming that it owed him £2.25 million as severance. In April this year, he won the case and the club has been asked to pay him the amount.

FAN FALLOUT

Amidst this turmoil, protests by indignant fan groups have been a constant feature. Average match attendance is down 44 percent from a peak of 25,000 when Venky’s took over in 2010. In January, only 5,000 fans turned up for Blackburn’s FA Cup game against Bristol City.

Fans are essential for a football club. Besides motivating players and intimidating the opposition, they drive match-day revenues and advertisers’ income. But Venky’s has lost them. It has even refused to establish any kind of dialogue with Blackburn supporters groups.

“Blackburn Rovers is not a business asset, a marketing tool or a plaything,” says Grabko. “It is a community of local, national and international supporters (both individual and commercial).” And failing to understand this difference has cost Venky’s majorly.

There’s been an influx of foreign owners in English football, which has disillusioned fans. They see it as a dilution in the essence of football clubs that are supposed to be pillars of community interaction and not corporate playthings with a brand value attached to them.

This is not the first time that club owners have ill-treated fans. Manchester United fans protested against the management of the Glazer family.

Liverpool fans were disenchanted with Messrs Gillett and Hicks, and played a big part in ousting them when the club was acquired by John Henry. But these teams are bigger than Blackburn Rovers.

However, the situation is not beyond salvage. Take for instance, Newcastle United and its owner Mike Ashley: The team realised its mistakes, made amends with fans and came back strong. Venky’s could perhaps take a leaf out of that.

MAKING THE MODEL WORK

Fulham FC, based in southwest London, is one club that has made the sugar-daddy model work. It is owned by Egyptian millionaire Mohamed Al Fayed, who’s the owner of Harrods. Fulham has consistently grown as a Premier League club since 1997 when Al Fayed took over. He recently bought equity worth £212 million in the club, and his funds have provided the team a platform to attract better players and have allowed them to reconstruct their tiny stadium.

Compared to Blackburn’s £18.6 million loss, Fulham made a profit of £1.2 million in FY2012 on revenues of £79.3 million. Al Fayed’s son, Karim, works with the Fulham FC management and is acquainted with ground realities all the time. Those who run the club, too, have constant access to the owners.

That’s not the case with Blackburn Rovers. The Raos of Venky’s have so far refused to communicate with the local government or the club’s supporters. They must open a dialogue with the BRST, if they are to turn things around. “If boards would make good decisions that fans—as major stakeholders—could understand, then fans wouldn’t get so frustrated,” says Rye.

The Venky’s Group didn’t respond to Forbes India’s questions.

Ayush Srivastava, special correspondent at football news website Goal.com, spoke to the Rao family and Shebby Singh. He says they are serious about persisting with the club and are putting money in sports in India.

Venky’s has sponsored I-League team Air India, the Celebrity Cricket League and the Super Fight League. It also runs a youth football programme in Pune and has sent its players to train in Blackburn. “The logic was to leverage the brand across Asia especially,” Srivastava says. “Venkatesh Rao reportedly said, in Vietnam, they were able to clear land for a factory easily because everyone knew who they were through Blackburn.”

PEOPLE POWER

Blackburn fans have had enough and now want to buy the club. They have already raised £3 million of the £10 million they require to launch a bid. They are buoyed by recent developments on England’s south coast where the Portsmouth FC supporters trust bought a 51 percent stake in the club, making it the largest fan-owned football club in English history. Portsmouth, too, is a small Premier League club relegated to the second division in English football.  It had spent beyond its means and had £117 million in debt in 2010. It is now languishing in the third tier. Fans have raised £3 million to buy the stadium.

It had spent beyond its means and had £117 million in debt in 2010. It is now languishing in the third tier. Fans have raised £3 million to buy the stadium.

This 51 percent fan-stakeholder model already exists in the hugely successful German league Bundesliga. It has the highest attendance rate and the lowest average ticket price among Europe’s major football leagues.

GAME ON

If the supporters group can buy BRFC, it could herald a new era for the English game where several clubs will be owned and controlled by fans, bringing in more stability, as opposed to non-committal sheikhs and businessmen owning them. And this fan-sharing model could be a lesson for all sports leagues, including cricket’s Indian Premier League.

“Rovers Trust [the official Blackburn Rovers supporters group] has raised current pledges of approximately £3 million to fund buying into the club. If it became public knowledge that Venky’s were open to the idea of a partial supporter buyout or were looking to sell the club, this number would increase significantly,” says Grabko.

The trust has initiated discussions with investors from the local community as well as institutional investors. Grabko says, “We believe that if Venky’s came to the table, gave us a price, and six months [time], we could realistically come back with a funded bid for a stake or potentially all of the club, if the price was sensible.”

Supporters Direct has led 30 clubs into a fan-ownership model. That includes Swansea City, a team currently in the Premier League, where fans own a 20 percent stake.

Rye feels that it is possible for football clubs to make money if they are run as businesses with fans at the core of all activities. “Since 1992, there have been over 92 insolvency episodes in English football’s top five divisions,” he says. “It is not about Indian owners or Russian owners or American owners. It’s about good owners owners who try to have a connection with the club beyond them just being a marketing tool.”

So what now for Venky’s?

In India, its plan to start an I-league outfit (Blackburn Rovers Pune FC) does not look like it will materialise, not until Blackburn makes it back into the Premier League in the UK. While Venky’s has sponsored several sporting events here, Blackburn, unlike a Manchester United or a Liverpool, lacks a large international fan base. The club relies mainly on regional support and Venky’s needs to go into a promotional overdrive in order to bring Lancaster locals back into Ewood Park.

First Published: May 20, 2013, 06:29

Subscribe Now