Uber's secret goldmine

Uber Eats could make up a tenth of the ride-hailing giant's revenue this year, impressive news for investors in its IPO. But well-capitalised rivals are already trying to tap the same vein

Chow time: Since the launch of Uber Eats, its leader, Jason Droege, has had 18 percent of all of his meals from Eats, including this bowl of noodles

Chow time: Since the launch of Uber Eats, its leader, Jason Droege, has had 18 percent of all of his meals from Eats, including this bowl of noodles

Image: Tim Pannel for ForbesWhen early investors were pitched on Uber’s original plan for a car-service app in 2008, it wasn’t until the second-to-last slide that they heard delivery could be another moneymaker for the business. Ten years later, delivery is no longer an afterthought.

According to projections from its CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber Eats is on track to deliver some $10 billion worth of food worldwide this year, up from an estimated $6 billion-plus last year. Uber takes a 30 percent cut and a delivery fee, then pays drivers, suggesting that Uber Eats could generate at least $1 billion in revenue this year, or an estimated 7 percent to 10 percent of the total. That means Uber Eats is already among the planet’s largest food-delivery services and ranks second in the US behind rival Grubhub (likely $1 billion in 2018 revenue) and ahead of competition like Caviar, Postmates and DoorDash.

Uber could certainly use the extra calories. The money-losing San Francisco-based company was valued at some $76 billion when it last raised money, in August 2018, and bankers hope its IPO, slated for later this year, could boost that to $120 billion. The problem is, there is no way Uber’s core ride-hailing business is worth that much. Its explosive growth is showing signs of slowing, and internationally the taxi service has struggled, selling its China operations to local rival Didi Chuxing in August 2016, as well as its stakes in Southeast Asia. Uber’s self-driving-car business, once considered the answer to rising driver costs, suspended testing and fired workers after an autonomous Uber killed a pedestrian in March 2018.

Now, as Uber prepares to tell investors why they should buy its stock instead of rival Lyft’s, Uber Eats looks like a distinguishing factor.

“When I first joined Uber, I think Uber was much more associated with ride-hailing and Eats was this interesting part-time endeavour,” says Khosrowshahi, who took over as CEO in August 2017. “It has since exploded, in a good way, into a truly significant business.”

But despite the growth, Uber Eats is losing lots of money, and even Khosrowshahi doesn’t know when it will be profitable. Potential Uber investors will have to decide: Is food delivery a smart bet on future growth or a fool’s errand in a crowded market?

It’s a question familiar to Jason Droege, the 40-year-old protégé of former CEO Travis Kalanick.

Droege has run Uber Eats since its 2014 inception, and some of the most critical voices he had to overcome were from Uber’s pre-IPO investors, who thought the company was on a path to recreate the terrible economics of Web 1.0 failures Web van, which blew through over $700 million trying to re-engineer grocery delivery in the late 1990s, and Kozmo.com, which spent nearly $300 million trying to deliver video games and convenience-store fare.Droege shrugs off the comparisons—and the competition. “The world was telling us this was a crowded space. But our hypothesis was it wasn’t,” he says.

Making money on delivery isn’t easy. Sure, Uber Eats gets a hefty chunk of a restaurant’s bill and charges a delivery fee, generally between $2 to $8. But Uber has to pay the driver to pick up and drop off the food, plus market the service. Uber’s share of the bill is lower, on average, than in the ride-hailing business. Restaurants are, at best, semi-willing partners that can ill afford a 30 percent blow to their bottom lines. And since Uber isn’t (yet) willing to have your meal share a ride with a paying customer, there are fewer network efficiencies to capitalise on.

Its largest competitor, publicly traded Grubhub, has proved you can make a profit in this business.

That success has made it a formidable rival, and it’s not the only one: Just in the US, Uber competes against Square subsidiary Caviar, well-capitalised startups DoorDash and Postmates, and the potential giant in the wings, Amazon.

Kalanick recruited Droege, with whom he had co-founded a file-sharing startup as undergraduates at UCLA, in March 2014 to head what was loosely called Uber Everything. His mandate: Find a service that could become as big as ride-hailing. Droege tried delivering everything from diapers and deodorant to daisies and dry cleaning. Nothing worked—except food.

After a few stunts like delivering ice cream and BBQ on the Fourth of July, Uber made its first serious attempt with Uber Fresh. Fresh had drivers circling city blocks with coolers full of soups and sandwiches ready for delivery within minutes. On launch day in Los Angeles in August 2014, the Uber team sold hundreds of meals in an hour and a half, a giant leap from the eight orders a day for deodorant. “The signal spike was big,” Droege says. Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s CEO, has left much of Eats to Droege. “Honestly, I’m there to do the corporate grunt work,” he says

Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber’s CEO, has left much of Eats to Droege. “Honestly, I’m there to do the corporate grunt work,” he says

Image: Carlo Allegri / ReutersIt was the right market but the wrong product.

Magical as it was to have a driver show up with a burrito in 5 minutes at the tap of an app, Droege realised customers would wait 30 minutes if they could order any meal they wanted. Internally the team quietly started work on Project Agora (Greek for marketplace) to launch Uber Eats. They started in Toronto in 2015, chosen because competition was lighter than in a city like New York, and then expanded to Miami, Houston and secondary cities like Tacoma, Washington. A couple of markets (Miami and Atlanta) became profitable in 2017, proving that the business was possible, at least in certain places. But just as Uber Eats was getting traction, Uber’s executive team fell apart in the wake of reports of sexual harassment, gender discrimination and questionable business ethics. Ultimately, Kalanick was ousted, and other groups, like self-driving cars, lost their department heads. But Droege and his team of nearly 2,000 remained mostly unscathed. He admits it was a “tough year”, but he told his team to keep their heads down and execute.

What’s most exciting to Uber executives is that many Eats customers don’t even use the ride-hailing service: Last year, four of every ten people who used Eats were new to Uber, giving the company access to fresh customers who might later be convinced to give the car service a try.

“Of all the side bets that Uber has made over the years, whether it’s autonomous or delivering other things or different modalities of transportation, this has come out as the clear number one in scale and executive attention,” says Mike Ghaffary, the former CEO of delivery rival Eat24.

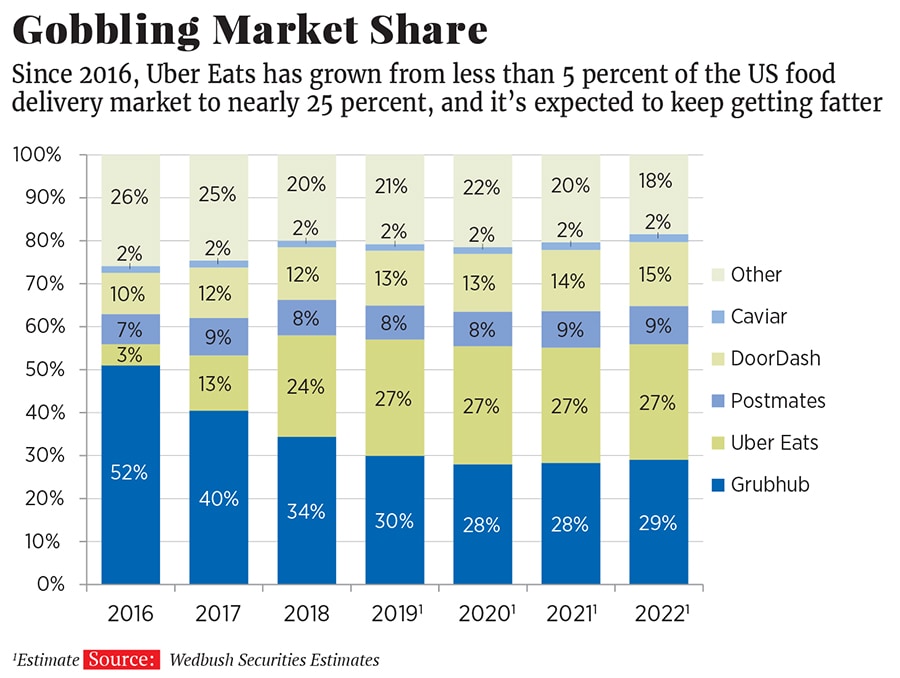

Eats is closing in on Grubhub. In 2016, Grubhub controlled over half the market, says Wedbush analyst Ygal Arounian.

Its market share dropped to 34 percent in 2018, while Eats’ grew from 3 percent to 24 percent. “The pace of their expansion has caught everyone off guard,” Arounian says.

But the tailwinds helping Eats, such as a generation turning to their phones first when hungry, also propelled its opponents. In 2018, DoorDash raised about $1 billion in venture funding and nearly tripled its valuation to $4 billion. Postmates also raised $400 million in the last six months of 2018 and now has a valuation of $1.9 billion. Both competitors also benefit from their single-minded focus on food delivery.

To trim costs, Uber Eats batches orders so a driver can pick up multiple meals at once. It’s also enticing customers with free delivery from restaurants that already have a courier en route. But Khosrow Khosrowshahi draws the line when it comes to pairing passengers with pad thai: “We don’t want your experience to suffer because it may be good for our business.”

To grow further, Uber Eats needs to win over more customers and restaurants.

Droege is betting partnerships with McDonald’s and Starbucks will entice customers to open the Uber Eats app instead of a competitor’s.

Uber is also copying Grubhub’s core business model and letting some restaurants do their own deliveries in exchange for a bigger take of the bill.

Success depends on convincing restaurant owners like Simon Mikhail, of Si-Pie Pizzeria in Chicago, that Eats trumps its rivals. Mikhail works with more than a dozen delivery services, but only Uber Eats approached him with an idea for a virtual restaurant, after it noticed how many folks in the neighbourhood were searching for fried chicken. Now he sells 160 pounds of chicken a week, exclusively through Uber Eats app. “They do cut into profit a little bit, but it’s worth it,” he says.

Will investors decide that Uber Eats is also worth it? That’s now up to Droege to deliver.

First Published: Feb 28, 2019, 12:51

Subscribe Now