The unicorn boom has just begun in US

Bubble? Hardly. Yes, many $1 billion startups are overvalued. But when viewed together and weighed against the first dotcom boom, they still represent a blockbuster investing moment

Founded 2013

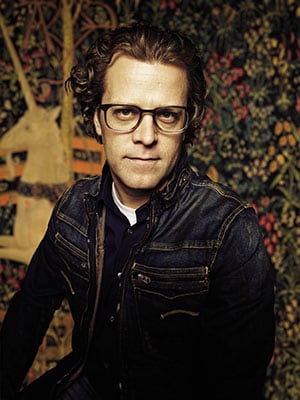

Ceo Parker Conrad

Zenefits

Value: $4.5 billion as of May 2015

Zenefits came up with a clever “freemium” business model to hijack the sleepy HR management software business. Give companies a free online service for easily managing their employees and worker benefits, and take a commission any time an employee signs up for something that plugs into it. Health insurance commissions are currently generating the vast majority of Zenefits’s revenue, but it gets a cut of payroll administration, commuter benefits, retirement plans, stock options and other ancillary services. The company is quickly reshaping the business of selling insurance and other HR services to small businesses, which employ roughly half of the US workforce. Just as Expedia and Travelocity replaced travel agents, Zenefits is replacing thousands of small, fax-machine-powered insurance brokers with an automated service that saves its customers countless hours of administrative work. Well over 10,000 businesses with anywhere from two to 1,000 employees have signed up. It’s a big number but a sliver of the millions of small and midsize businesses in the United States. “What we do is much broader than insurance,” says Parker Conrad. “We are trying to be the system of record for employee information. It really becomes an operating system for the business.”

—MHFor the anxious throng worried about spiraling startup valuations—a group now big enough to pass for conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley—Zenefits could be the poster child for collective panic. The two-and-a-half-year-old company, which sells cloud software to help businesses manage HR, payroll and benefits, has been bid up recently to $4.5 billion, a nosebleeding 45 times this year’s forecasted revenue and well into the ‘unicorn’ stratosphere. The company is worth more than Sears and Columbia Sportswear and their combined two centuries of operations. Its value has increased $6.6 million for every workday it has been in business.

For companies like Zenefits, the very name unicorn—a venture-backed private company sporting a valuation above $1 billion—carries irony. The term derives from historic rarity: The idea that an eBay or a Google or a Facebook is a kind of magical occurrence, one that single-handedly turns a portfolio into a blockbuster, a venture capitalist into a superstar. Now it’s a downright common benchmark and one that’s invoked with a sense of dread as their numbers grow. We count 140 unicorns globally, up from 75 at the end of last year. Most are US firms, but it seems like a new one is minted every week or two in China or India.

Unicorns, critics say, represent the next risk bubble: So many largely unprofitable firms lacking in rigorous auditing or public disclosures. “We may be nearing the end of a cycle where growth is valued more than profitability,” veteran venture capitalist Bill Gurley of Benchmark tweeted in August. “It could be at an inflection point.” Sceptics point to the mediocre post-IPO performance of former unicorns Pure Storage and Box as evidence that the chickens have come home to roost. Reports of startups with unworkable business models surface with increasing frequency.  Founded 2010

Founded 2010

Ceo Patrick Collison

Stripe

Value: $5 billion as of July 2015

Since Patrick Collison founded Stripe with his brother John in 2010, it has become one of the hottest destinations for tech talent in San Francisco. Despite a modest sales and marketing team of just 20 people, Stripe has a payments infrastructure that is already helping hundreds of thousands of businesses process billions in transactions every year. Its customers include fast-growing companies like Lyft, Kickstarter and Twitter and established giants like Salesforce and Rackspace. Stripe has also woven its technology into some of the ubiquitous digital commerce services like Apple Pay and Alipay. “The market is so large,” says Collison. “There are very few businesses that don’t move money around online in some capacity or another. It’s not the valuation that’s so surprising but that it’s possible to build businesses of

such scale so quickly.”

—MHAll fair points, when looking at individual companies this year. But a bubble implies a systemic problem and an existential danger, and when you view these high-growth startups as a long-term portfolio, that’s simply not the case. (See the entire class of 2015 unicorns, starting on p 78.) Taken as a whole, the 93 firms based in the US (Americorns?) are worth $322 billion, 14 percent less than Microsoft and a bit more than Intel and Cisco combined. Which would you rather own long term? Microsoft or a basket that includes Uber, Airbnb, Snapchat and Pinterest along with scores of others, a few of which will surely emerge as future PayPals, Twitters or Fitbits? Is that even a hard decision? And if not, what are we worried about?

Quite the contrary: If you’re looking for growth, the unicorns minted in the last few years may well be one of the most attractive investments anywhere. (Obviously you can’t buy the whole basket of unicorns, but we did find several retail mutual funds that give you broad exposure to them.)

Founded 2010

Founded 2010

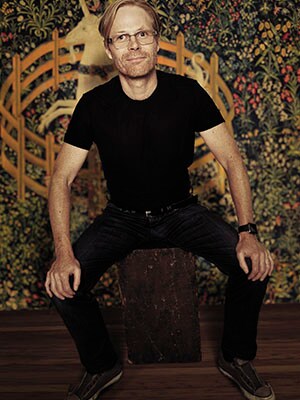

CEO Josh James

Domo

Value: $2 billion as of April 2015

Josh James knows plenty about running a business in a bubble. He started his first unicorn, Omniture, in 1996. At the height of the dot-com frenzy he received offers for the company simply based on the number of engineers it employed. James’s refusal to sell proved prescient. He took Omniture public in 2006 and sold it to Adobe for $1.8 billion three years later. Investors in Domo, a web-based business intelligence and analytics service, are more hard-nosed about scrutinising its metrics but get the economics of software-as-a-service, James says. “People understand the model,” he says. Since launching in 2012, Domo has been doubling every year, and it expects to pass $100 million in revenue in 2016. Most Domo customers, which include GE, Nissan and MasterCard, not only stay but increase their spending by 170 percent in the second year. The key to weathering any downturn, James says, is a healthy balance sheet. Domo has raised more than $450 million from investors. “If you don’t have enough cash to get to break-even, you don’t control your destiny,” James says. “We have enough cash to get us to break-even.”

—MHLook more closely at Zenefits: It booked $20 million in annually recurring revenue in its first full year of operations and is on track to reach $100 million this year. That’s growth the more established enterprise software titans could only have dreamed of when they were startups. It took Salesforce (market cap $50 billion) and Workday ($15 billion) more than five years each to pass $100 million in revenue. Zenefits has raised eyebrows for spending much of its revenue to fuel its growth (adding 1,600 employees to date), but it takes the company just six months to recoup the cost of acquiring a customer. Its CEO boasts that it makes more per user than most other “software as a service” companies. “I have no idea if we are in a bubble,” says Zenefits CEO Parker Conrad. “I’m a terrible investor myself. But I know we have some of the most incredible unit economics.”

Here’s what’s fueling that kind of performance and why this all isn’t Pets.com redux: The number of people connected to the Internet has surged from 400 million in 1999 to 3 billion last year. The eight-year-old mobile revolution shows no sign of abating (just look at Apple’s iPhone sales), and it is enabling forms of previously unthinkable, more efficient business models. Airbnb, which owns no accommodations, has put up more than 30 million guests so far this year. Uber, which owns no cars, drives 3 million people every day. The same digital transformation is hitting farming, health care, financial services and retail.  Founded 2001

Founded 2001

Ceo Borge Hald, President Amy Pressman

Medallia

Value: $1.25 billion as of July 2015

Medallia survived two popped bubbles (dot-com and credit crisis) over its 14-year “overnight success”. While there are plenty of companies battling it out in the customer relationship management (CRM) space, the Palo Alto company deals in “customer experience,” providing a platform of surveys, text analytics and social media tools for businesses to track what their customers are really thinking and saying. That enables clients like Hilton to understand how a customer felt about that new mattress or Delta to see when fliers aren’t enjoying their delays (and are angrily tweeting about it). In a world where all brands are focussed on being “customer-centric”, more than 500 companies swear by Medallia, whose average annual contract runs in the seven figures. Says President Amy Pressman, who co-founded the company with her husband, Borge Hald: “A lot of companies are afraid that they’re going to be blindsided by something that’s there in plain view, but they’re so overwhelmed with data.” Sequoia Capital partner Doug Leone cold-called the company in 2011 and was in its offices 24 hours later discussing deal terms. “In 2015 every single company says they’re ‘customer-centric.’&thinsp” Medallia has raised more than $250 million to date, the majority of which comes from Sequoia.

—Ryan MacIn light of these changes the amount of money pouring into private tech companies is down- right modest: $48 billion in 2014, compared with $71 billion in 1999. When adjusted for inflation, dollars fueling tech startups last year were roughly a third of what they were at the peak of the dot-com bubble, and when adjusted by the number of people online, they were about one-tenth. One-tenth. What’s more, rather than being distributed among a large number of early-stage startups— which by definition are the riskiest ones—most of the investment is now concentrated on a far smaller number of more established companies.

Because they’re betting on fewer but bigger companies, blue-chip VCs—including Zenefits backers Andreessen Horowitz, Khosla Ventures and Founders Fund—and institutional investors like Fidelity and TPG are willing to lean forward further than usual. “Zenefits is growing at a rate that people haven’t seen before against a massive market opportunity,” says Scott Kupor, managing partner at Andreessen Horowitz, who scoffs at the notion that institutional investors don’t know how to value startups. “When smart public market investors build a financial model incorporating that growth rate against their required net internal rate of return, the valuation makes sense.”

Founded 2006

Founded 2006

CEO Anne Wojcicki

23andMe

Value: $1 .15 billion as of October 2015

It’s been a tumultuous nine years for this Silicon Valley maker of over-the-counter genetic tests. It launched with visions of being everyone’s portal to the secrets of their DNA. Then two years ago the Food & Drug Administration told 23andMe’s Anne Wojcicki she could no longer sell the company’s tests for any use relating to health. She was also, by the way, in the midst of a divorce from her husband, Google cofounder Sergey Brin. “Two thousand fifteen was better than 2014 and 2013,” she says. “Without a doubt.”

Rather than punt, Wojcicki figured out what she could do to make money of the 900,000 customers who had eagerly contributed their genetic data to 23andMe’s research database. In January she announced a drug-discovery collaboration with Genentech worth an estimated $60 million in milestone payments. In April Wojcicki hired Genentech’s head of early-stage R&D to run its own in-house drug-invention operation. Even a single blockbuster drug could generate more revenue than selling 23andMe’s $99 test to every adult in the US.

Now Wojcicki says she hopes the FDA will allow 23andMe to market some health- related tests again. “There’s a huge value in actually being the only one who’s gone through the FDA process and can sell directly to consumers,” she says.

The coup de grâce: In October 23andMe raised $115 million from investors, including Fidelity, ticking up its unicorn valuation a bit to $1.15 billion.

To be sure, drug discovery is hard, but Wojcicki won’t give up, and she could end up controlling a new gateway to the health care system. “This is a multi-year vision for how we bring genetics en masse to consumers,” Wojcicki says. “This is just step one.”

—Matthew HerperThe Chicken Little crowd likes to point to the new generation of web giants, the Pinterests and Snapchats, which are valued more by their users than by their revenue—the same issue that got everyone in trouble during the dot-com bubble. The difference—and it’s a significant one—is that now there are well-understood and proven revenue models for social media platforms. Plenty cried bubble when Google purchased YouTube for $1.65 billion in 2006, when Facebook got valued at $15 billion in 2007 and again when Facebook paid $1 billion for Instagram in 2012. Now YouTube is widely considered one of the best acquisitions of the internet era, Facebook is worth $250 billion and Instagram is expected to bring in $600 million in revenue this year and already has one-third more users than Twitter, which despite its well-publicised challenges is still valued at about $20 billion.

A similar dynamic is at work with software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies. Josh James, who sold his first enterprise software company, Omniture, to Adobe for $1.8 billion in 2009, says his new business-intelligence startup, Domo, is growing far faster into its valuation, $2 billion. “There’s a true understanding of SaaS as a business,” James says. For every dollar Domo invests, it gets a dollar back in the first year and $1.70 back in the second year, he says. “That’s a pretty good return profile.”

The presence of so many unicorns is not necessarily a signal of height- ened risk. High-growth companies are merely substituting private market capital for the public markets. And why not? Cash is plentiful, and staying private longer avoids the head- aches of an IPO and the quarterly shareholder dance. In 2000 venture- backed tech companies raised $42 billion in 261 IPOs, compared with $10 billion in 53 IPOs last year. What’s more, much of the value appreciation that used to follow an IPO is now occurring before companies go public. More than 99 percent of Microsoft’s value was created in the public markets for Google the figure is more than 90 percent and for Facebook just north of 60 percent. Twitter? Its entire $20 billion in market value accrued when it was private.

Some valuations do get propped up from a fear of missing out as investors all chase the next LinkedIn or Salesforce. No doubt they’re throwing money at companies that will never reach those heights. Many will fail altogether. And the VC firms, hedge funds and mutual funds are often able to demand favourable terms—downside protections and anti-dilution measures—that would make them whole even if values decline. Those factors have certainly contributed to artificially pumping up some valuations. In some areas, notably China, which is suffering from an overall economic slowdown, a pullback could be significant.

But even a selective correction won’t trigger an across-the-board crash. Not a chance. Too many unicorns have proven they have growing, sustainable businesses. Despite the lackluster IPOs of Box, New Relic and Pure Storage, these are not dot-com-crash disappointments—merely healthy companies that were a bit over-valued. They’re not about to fail and could still soar past their IPO prices in a year or two (remember Facebook?). And even if investors get spooked and decide to stop lavishing cash on unicorns, most companies have the balance sheets and where- withal to survive long winters. There might be some belt-tightening and some painful layoffs but not a sudden pop. “For many companies it’s striking how long the runway is,” says investor Peter Thiel. “It suggests people are more fearful than greedy.”

That’s largely why someone like Chris Wanstrath, the CEO of GitHub, a $2 billion cloud-based management service for software development, doesn’t lose sleep over the bubble talk. GitHub was profitable for four years before it raised two rounds totaling $350 million. It’s now plowing cash into growth but could return to profitability if it had to. “We took the funding because things are going well, and we want to accelerate our business,” Wanstrath says. Big customers such as Target, John Deere and Ford are using GitHub to modernise their operations through software. “That’s not going to change even if there’s a downturn,” Wanstrath adds. “We’ll be okay, really.”

First Published: Nov 19, 2015, 06:44

Subscribe Now