The toll collector

While Wall Street wasn't looking, accountant Bruce Flatt became a billionaire by assembling one of the world's largest portfolios of office buildings, power plants and infrastructure projects—and maki

Bruce Flatt

Image: Franco Vogt for ForbesJust off a 14-hour commercial flight from Dubai, Brookfield Asset Management chief Bruce Flatt stares into a gaping hole in the ground that looks like open-heart surgery performed on an entire city block in Manhattan. Piles of beams, mazes of scaffolding and even active railroad tracks crisscross each other endlessly.

“The amount of steel here is enormous,” Flatt shouts over a cacophony of honking car horns, grinding cement mixers and moving cranes at one end of the notoriously clogged Lincoln Tunnel. More than 17.2 million pounds of steel, to be precise, enough to anchor a 67-storied glass office tower. Two more towers are also going up, along with a 30-floor boutique hotel and a 16-storied trapezoidal glass office building with 26-foot-high ceilings and floors the size of football fields—much of it suspended over railroad yards. Dubbed Manhattan West, this 7-million-square-foot, $5 billion project encompasses two square city blocks.

And yet it’s completely invisible in the public consciousness—the vast majority of New Yorkers have never heard of it. Most people assume it’s part of the adjacent Hudson Yards development, a $25 billion project from billionaire Stephen Ross and his Related Companies that will feature 16 skyscrapers and 18 million square feet.

That’s fitting. The high-profile Stephen Ross has an oceanfront Palm Beach mansion, owns the Miami Dolphins and travels in the same circles as Donald Trump. Bruce Flatt is an accountant from Manitoba who lives in a quiet Toronto neighborhood and often commutes by subway.

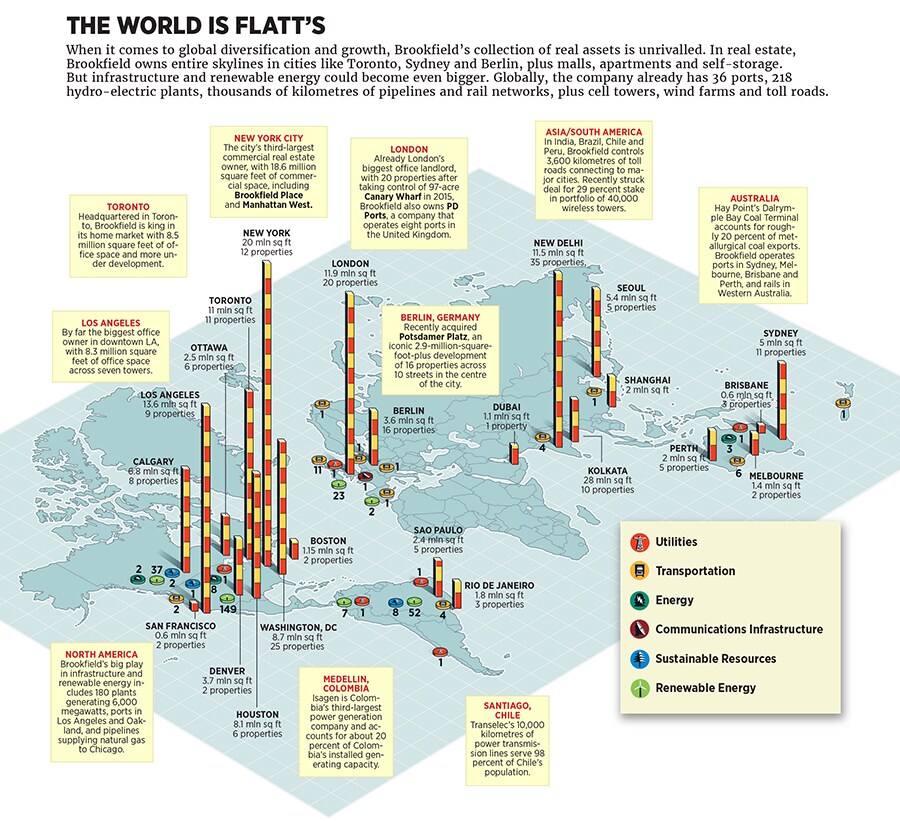

But if you’re comparing their portfolios? It’s not even close. Brookfield quietly owns entire city skylines in places like Toronto and Sydney. It’s the biggest office landlord in London and downtown Los Angeles. In Berlin, it owns Potsdamer Platz and, in London, Canary Wharf, two of the biggest real estate developments in Europe. It has 14,200 hotel rooms, including Atlantis in the Bahamas and the Diplomat in Florida, and scores of shopping malls courtesy of divisions like Rouse Properties and General Growth, and several high-end Brazil shopping centres. In all, Brookfield owns some 400 million square feet of commercial space.

And that’s just the real estate. Flatt’s true passion is infrastructure, which he sees as a $35 trillion opportunity that, like Manhattan West, is hiding in plain sight. “Infrastructure will be an enormous asset class for institutional investors in the coming 25 years,” Flatt insists.

Brookfield owns 218 hydroelectric plants on 82 river systems in North and South America. In France, Brookfield has the largest independent owner of cell towers. In Chile, its electric power lines serve 98 percent of the population. In Ireland, it owns 20 percent of the country’s wind-farm capacity. It owns 36 ports in the UK, North America, Australia and Europe, and in India and South America it manages 3,600 kilometres of toll roads. All told, Brookfield has 2,000 projects across 30 countries on five continents, encompassing $250 billion in assets and 70,000 employees. President Trump talks about an infrastructure plan—Bruce Flatt is actually executing one.

And Wall Street loves it. Despite Brookfield’s low profile, its stock has returned 1,350 percent since Flatt took the helm in 2002, versus 183 percent for the S&P 500—that’s a Buffettesque 19 percent annual average, buoyed by assets that generated some $25 billion in revenues last year and net profits of $3.3 billion. With a $36 billion market cap, Brookfield is the size of KKR, Apollo, Carlyle Group and Colony Northstar combined. “Bruce is not afraid to make large bets when he sees an opportunity,” says Jonathan Gray, Blackstone’s real estate chief and a possible heir to Stephen Schwarzman. “He buys high-quality, long-duration assets—be they pipelines or electric grids or large pieces of real estate. Between the combination of yield and appreciation, they generate strong returns over time.” At 51, Flatt just joined the Forbes Billionaires list, with a net worth of $1.3 billion.

Flatt has been called Canada’s Warren Buffett not only because he’s a contrarian, long-term investor but also because his investment strategy relies less on price than on patience and the power of compounding income streams. “We will pay more for quality because in the fullness of time, real assets will generally always go up in value,” Flatt says. “We’d rather earn a 12 percent to 15 percent net return over 20 years than a 25 percent over three.”

In fact, if ever there were a collection of sleep-well-at-night investments that might one day rival the safe-haven status of US Treasury bonds or gold, you could argue that it’s the well-diversified trove of real assets in Brookfield’s $250 billion portfolio. It’s essentially a call on the future of civilisation itself. And it’s about to get far bigger.

If Flatt is trying to cultivate the Buffett comparisons, his Toronto digs certainly encourage it. Modest home? He lives in a two-storeyed brick townhouse barely set back from the sidewalk. Humble office? A drab gray cubicle, positioned against a window looking onto a courtyard of an office complex that Brookfield owns. Contrarian outlook? The only piece of art visible from Flatt’s desk is a framed cartoon depicting a herd of white sheep moving towards a cliff as a single black sheep heads in the opposite direction.

His break came early. His father was an executive at a mutual fund company in Manitoba, and Flatt, numerically inclined, joined an accounting firm in Toronto out of college.In 1990, at 25, he was hired at Brascan, a conglomerate controlled by Peter and Edward Bronfman, two heirs to the Seagram fortune. He eventually rose to become vice president of its merchant bank and gained a seat in the engine room of one of Canada’s largest companies, with holdings like Labatt Beer, the Toronto Blue Jays and millions of acres of timberland. Then came trouble. Brascan’s interests were built by Peter Bronfman and a South African investor named Jack Cockwell, who financed its ambition through a web of intermingled corporate holdings. The structure faltered during the early 1990s downturn, and troubled Brascan was forced to sell its beer, baseball and forestry interests.

Flatt and a number of young partners began to rebuild Brascan. Its stock was deeply depressed, and, by the mid-1990s, Bronfman had stepped aside, selling his shares to a partnership that distributed stock to the company’s upper ranks. For Flatt, it was a billion-dollar opportunity: By borrowing, he was ultimately able to gain control of a large number of shares with a chance for immense wealth if he and his partners could devise a better strategy.Having seen the hazards of corporate overreach, Flatt forged an investing style to capitalise on the miscalculations of others. “We were young in our careers and watched very difficult markets in the late 1980s and early 1990s,” he says. “That was quite impressionable on us to how we run the business today—never put yourself in a situation where you have to sell something in an environment where you should be buying.”

The opportunity came quickly. Another humbled Canadian giant, Olympia & York, filed for bankruptcy in 1992 after heavy losses in developing London’s Canary Wharf. Flatt scooped up O&Y senior debt and organised a plan with creditors, including Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing, beating out Apollo and Tishman Speyer. When the dust settled, Flatt controlled the World Financial Center—and a block on the West Side of Manhattan that he would sit on. Flatt listed the real estate trove on public markets in 1997 under the name Brookfield Properties. He then proceeded to buy out his minority partners. The stock quickly soared, reviving parent Brascan.

History repeated ahead of the next downturn. On 9/11, Flatt sprang into action, first reassuring investors that the World Financial Center had been mangled but not toppled. Then he hopped in a limousine and travelled from Toronto to Lower Manhattan to check on his workers and buildings. Alongside executives like John Zuccotti, a former deputy mayor of New York, Flatt and his team organised a months-long cleanup. When the crisis passed, he was anointed CEO by Brascan’s partnership, capping a dramatic ascent for the 36-year-old.

Once in charge, Flatt streamlined Brascan’s sprawling operations into three lines: Real estate, renewable energy and infrastructure. On top of these divisions would sit an asset-management unit to invest outside funds—including co-investments from sovereign wealth funds—designed to generate fees and have capital ready for market dislocations.

And those dislocations kept coming. After the Enron debacle, for example, Flatt’s renewable-energy business acquired hundreds of hydroelectric plants. By 2005, Flatt decided to rebrand the whole Brascan operation under the Brookfield name.

On the eve of the financial crisis in 2007, hundreds of sceptical investors gathered at the New-York Historical Society for a one-day conference on the fragile state of the global economy. Pollyannaish Merrill Lynch economist David Rosenberg warned that a severe recession was imminent. Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman railed against a new Wall Street creation called CDOs, which he predicted would soon implode.

But when the young chief executive of Canada’s Brookfield Asset Management got up to speak, he turned the topic to infrastructure—a $35 trillion opportunity hiding in plain sight.

Forget the gloom. Pipelines, wireless towers, power generation, ports and toll roads—the backbone of the global economy—would soon become the holy grail investment product for trillions of dollars stagnating in pension funds and savings. “David [Rosenberg’s] presentation is probably about the next six months,” Flatt told the doomsday-obsessed audience. “Mine is more relevant to the next 25 to 60 years.”

Recession or not, this market could be bigger than real estate—and Flatt was ready once again to exercise his penchant for buying during desperate times, only now on a massive scale.

First up: Australian construction and real estate giant Multiplex, on the verge of collapse after massive cost overruns in building London’s Wembley Stadium. Brookfield acquired it for a bargain $3.8 billion, gaining a global construction business, $6.6 billion in real estate and an operating toehold in Australia. Next, in 2009, Brookfield spent $1.1 billion acquiring a major stake in the bankrupt infrastructure giant Babcock & Brown, control of Britain’s third-largest port operator and a 50 percent interest in the world’s largest coal-export terminal in Queensland, Australia, adding $8 billion in infrastructure assets.

A year later, Brookfield, in partnership with Ackman, led the recapitalisation of bankrupt mall operator General Growth, ponying up $2.5 billion for a 26 percent stake, one of the seminal investment scores of the crisis. So far it has yielded Brookfield and its investors $10 billion in profit. Flatt remains chairman of General Growth, and Brookfield is a 35 percent shareholder. “We didn’t get in trouble before the crisis, so we were able to continue to grow and we were running fast coming out,” Flatt says. “We could move money where money was needed.”

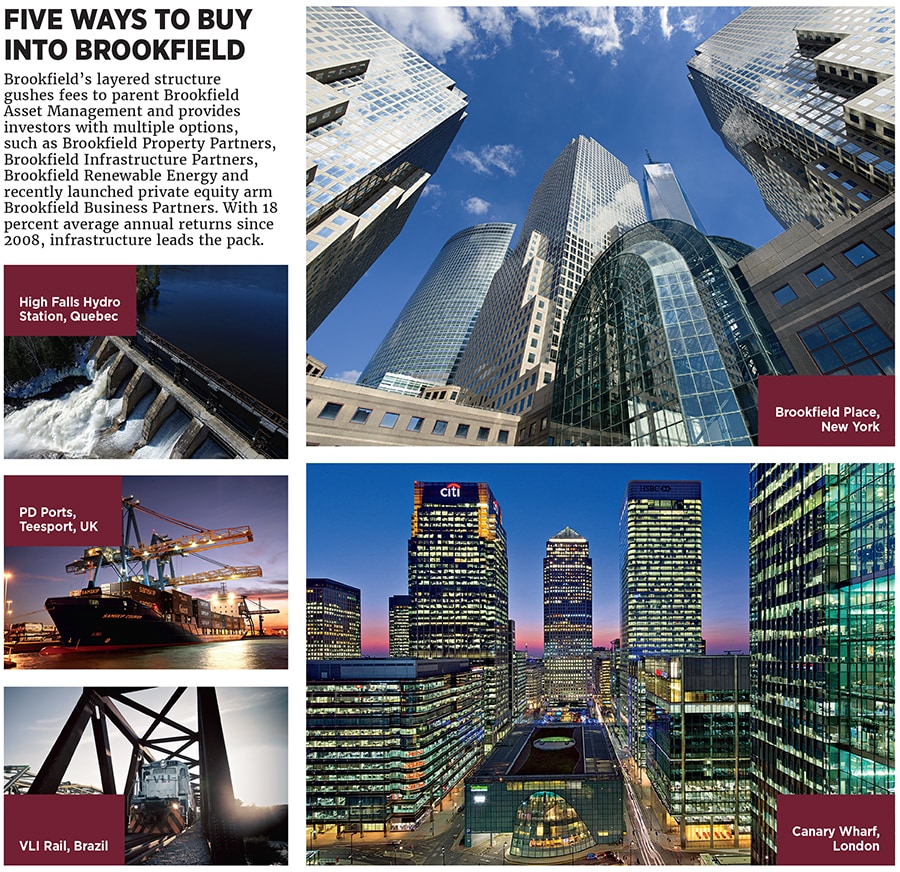

undefined Pipelines, wireless towers, power plants, ports and toll roads will be a holy grail investment product for trillions stagnating in pension funds [/bq] As brilliant as Flatt’s purchases were his exits. Beginning in 2008, he took each of his divisions public on the NYSE (separate from the already public real estate arm, now known as Brookfield Property Partners). First, infrastructure (Brookfield Infrastructure Partners), then renewable energy (Brookfield Renewable Partners), then the private equity arm (Brookfield Business Partners). All this in addition to the holding company itself, Brookfield Asset Management. Collectively, Brookfield’s five public entities carry more than $70 billion in public market value.

The holding company’s stakes in the four derivative companies range from 30 percent to 75 percent, forming a byzantine structure that feeds the parent with a perpetual and growing stream of cash, since it gets fixed fees plus a 1.25 percent annual management fee based on the value of its listed partnerships and performance fees of 15 percent to 25 percent based on the level of the dividends. Fold in its dozens of private funds, and Flatt’s flagship found itself generating $1.1 billion in fee revenues, up 31 percent year-over-year and a 160 percent-plus gain from 2012. Brookfield predicts it will generate $2.4 billion in annual fees by 2021.

Besides the annuity of charging people to manage their money, this structure also carries a big tactical advantage. Because permanent capital is built into its public vehicles, roughly half of Brookfield’s funding never has to be returned to investors, allowing it to compound investments and build more muscle and flexibility than almost any investment firm on earth. “These are lifelong entities,” Neuberger Berman’s Charles Kantor says. “I think that was brilliant.”

One distinct difference between Brookfield and Berkshire Hathaway: While Buffett’s annual shareholder meeting is basically a carnival of capitalism, Brookfield’s annual investor meeting is a sober gathering of suits. There are no members of the press or doe-eyed fans, just financial analysts and money managers with sharpened pencils ready to absorb head-spinning financial math that is both Brookfield’s strength and its Achilles’ heel.

At the start of his presentation, Flatt strolls to a podium: “There’s really nothing different that we’re doing or we’re proposing to do with this company, and essentially nothing has changed.” But this humility is a ruse. Brookfield had a banner 2016, and he’s brimming. “The numbers are bigger, money has been raised faster, and therefore the returns should be higher and come quicker,” he says.

First the money: Infrastructure has become Wall Street’s hottest product—in 2016, $62.5 billion was raised at 59 infrastructure funds—and Brookfield has first-mover advantage. Over the past year, Brookfield closed $27 billion in private funds, one of the biggest gatherings of cash in the history of Wall Street, led by $14 billion for infrastructure investments and driven by Brookfield’s network of 450 sovereign wealth investors, pension funds and endowments.

There were also more deals: $18 billion was spent mostly in markets where investors see calamity but Brookfield’s flexibility allows it to buy. Brazil, roiled by a recession and a corruption scandal, has been a key Brookfield target. So far, Petrobras sold it NTS, the country’s pipeline giant, for $5.2 billion—Brookfield’s ability to close without financing conditions was the key to the deal. Then it agreed to buy a 70 percent stake in the nation’s largest private water and sewage company, Odebrecht Ambiental, whose holding company CEO was carted off to jail in 2016. Some $6.9 billion was spent alongside partners to buy Australia’s biggest rail-freight and container-port operator. Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz, once a no man’s land by the Berlin Wall, was acquired for a reported $1.4 billion. Now Brookfield is helping Macy’s come up with a plan to extract value from its vast real estate, as its CEO departs amid plummeting shares and a battle with a hedge fund activist. In March, Brookfield struck a deal to take control of TerraForm Power and TerraForm Global, the crown jewel solar and wind assets of bankrupt SunEdison.

All told, Brookfield is on a 100-transaction-a-year pace, fed by 700 global deal scouts. Flatt presides over small teams that review each deal. He boasts that he hardly ever turns down a pitch because the firm’s strict underwriting standards have been institutionalised over many decades.

These executives forgo the kind of immense overnight riches that partners sometimes get at private equity firms and take the slow-but-steady path, gained by appreciation of its stock. In this model, Flatt and his team, unlike at so many funds, are largely aligned with their investors. Insiders own roughly 20 percent of Brookfield Asset Management Flatt’s $1.2 billion in holdings is the largest stake, while others, like former CEO Jack Cockwell, hold interests in the hundreds of millions.

Despite its long-term call on global productivity and growth, Brookfield carries risk. During the crisis in 2008 and 2009, as Flatt was doubling down, Brookfield’s stock plunged more than 70 percent. Bribery and corruption remain an issue for a company running so many arteries in so many countries. In 2012, for example, Brookfield was hit with a civil lawsuit in Brazil, as well as an SEC and Department of Justice investigation for alleged bribery by some of its employees. The SEC and DOJ investigations closed with no charges.

There are also geopolitical risks. The $5.2 billion pipeline deal was suspended in February by a Brazilian court a phalanx of lawyers challenged the injunction and had it overturned. And unexpected events like Brexit roil projects like Canary Wharf.

But Flatt figures to have a solid two-decade timeline to see his projects through (or much longer if he continues to emulate Buffett) and a corporate mandate that matches such patience. “Brexit may happen over the next ten years. But London is still going to be one of the great cities of commerce,” Flatt says, noting that a high-speed railway will soon connect Heathrow to Canary Wharf in 40 minutes. “Over the next 20 years, we are going to make an enormous amount of money.”

First Published: May 19, 2017, 04:29

Subscribe Now