The Ozmens' galactic gamble

Eren Ozmen and her husband spent the last quarter of a century carefully building Sierra Nevada from a tiny, 20-person defence firm into a multibillion-dollar aerospace concern. Now she's betting thei

Eren Ozmen ranks 19th on Forbes’s list of America’s richest self-made women Photographs by Tim Pannell for Forbes Makeup and hair by Suzana Halilli (using targeted skin and temptu) Stylist: Barry Samaha. Eren Ozmen wears a knit jacket by St. John ($1,695) and Affinity necklace by Coomi ($58,000).Even in the bloated-budget world of aerospace, $650 million is a lot of money. It’s approximately the price of six of Boeing’s workhorse 737s or, for the more militarily inclined, about the cost of seven F-35 stealth fighter jets. It’s also the amount of money Nasa and the Sierra Nevada Corp spent developing the Dream Chaser, a reusable spacecraft designed to take astronauts into orbit. Sierra Nevada, which is based in Sparks, Nevada, and 100 percent owned by Eren Ozmen and her husband, Fatih, put in $300 million Nasa ponied up the other $350 million. The Dream Chaser’s first free flight was in October 2013 when it was dropped 12,500 feet from a helicopter. The landing gear malfunctioned, and the vehicle skidded off the runway upon landing. A year later, Nasa passed on Sierra Nevada’s space plane and awarded the multibillion-dollar contracts to Boeing and SpaceX.

The original Dream Chaser, which looks like a mini space shuttle with upturned wings, now serves as an extremely expensive lobby decoration for Sierra Nevada’s outpost in Louisville, Colorado. But the nine-figure failure barely put a dent in the Ozmens’ dream of joining the space race. Within months of the snub, the company bid on another Nasa contract, to carry cargo, including food, water and science experiments, to and from the International Space Station. This time it won. Sierra Nevada and its competitors Orbital ATK and SpaceX will split a contract worth up to $14 billion. (The exact amount will depend on a number of factors, including successful missions.) The new unmanned cargo ship, which is yet to be built, will also be called Dream Chaser.

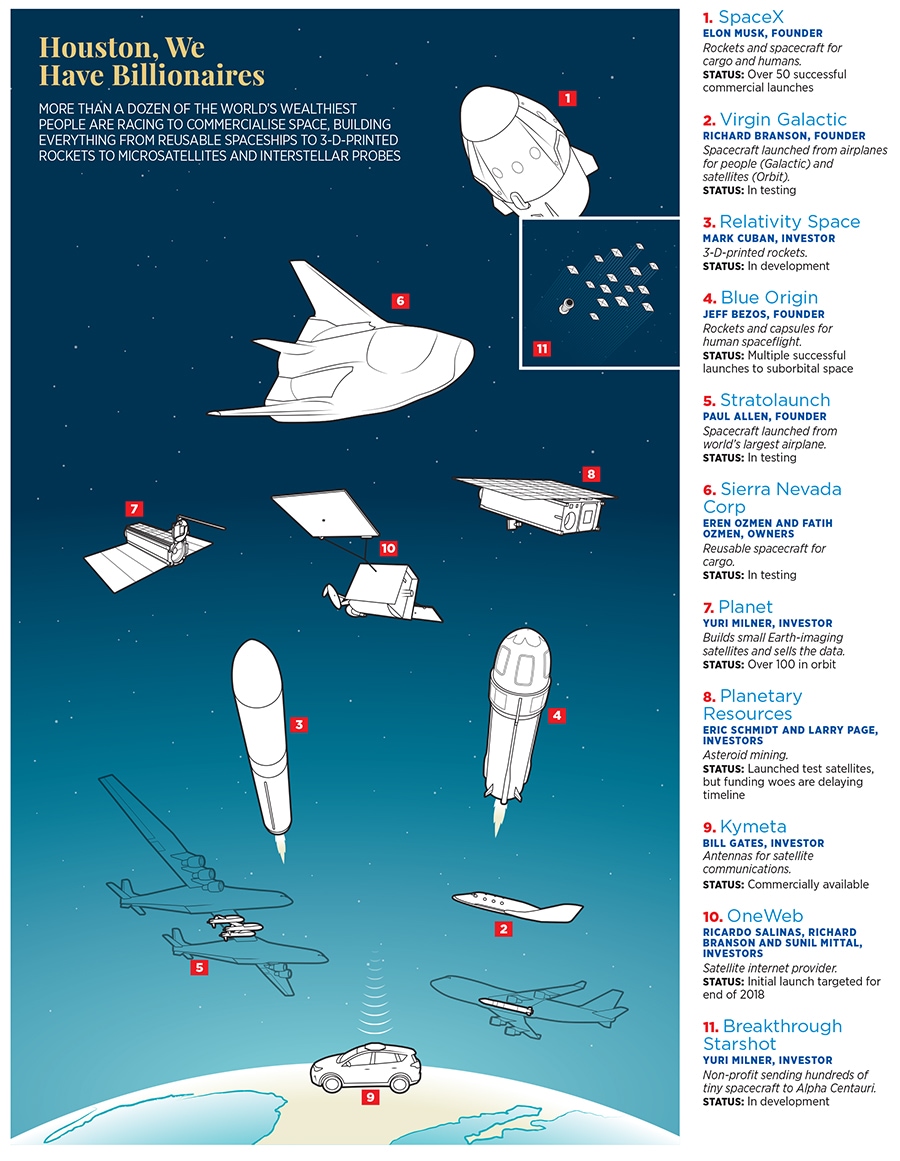

The Ozmens, who are worth $1.3 billion each, are part of a growing wave of the uber-rich who are racing into space, filling the void left by Nasa when it abandoned the space shuttle in the wake of the 2003 Columbia disaster. Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic are the best-known ventures, but everyone from Larry Page (Planetary Resources) and Mark Cuban (Relativity Space) to Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin) and Paul Allen (Stratolaunch) is in the game (see Houston, We have Billionaires). Most are passion projects, but the money is potentially good, too. Through 2017, Nasa awarded $17.8 billion toward private space transport: $8.5 billion for crew and $9.3 billion for cargo.

“We’re doing it because we have the drive and innovation, and we see an opportunity—and need—for the US to continue its leadership role in this important frontier,” says Eren Ozmen, 59, who ranks 19th on our annual list of America’s richest self-made women.

Until now, few had heard of the Ozmens or Sierra Nevada. Often confused with the California beer company with the same name, the firm even printed coasters that say #notthebeercompany. The Ozmens are Turkish immigrants who came to America for graduate school in the early 1980s and acquired Sierra Nevada, the small defence company where they both worked, for less than $5 million in 1994, using their house as collateral. Eren got a 51 percent stake and Fatih 49 percent. Starting in 1998, they went on an acquisition binge financed with the cash flow from their military contracts, buying up 19 aerospace and defence firms. Today Sierra Nevada is the biggest female-owned government contractor in the country, with $1.6 billion in 2017 sales and nearly 4,000 employees across 33 locations. Eighty percent of its revenue comes from the US government (mostly the Air Force), to which it sells its military planes, drones, anti-IED devices and navigation technology.

Space is a big departure for Sierra Nevada—and a big risk. The company has never sent an aircraft into space, and it is largely known for upgrading existing planes. But it is spending lavishly on the Dream Chaser and working hard to overcome its underdog reputation.

“Space is more than a business for us,” says Fatih, 60. “When we were children, on the other side of the world, we watched the moon landing on a black-and-white TV. It gave us goose bumps. It was so inspirational.” Eren, in her heavy Turkish accent, adds: “Look at the United States and what women can do here, compared to the rest of the world. That is why we feel we have a legacy to leave behind.”

There are plenty of reasons that Nasa gave Sierra Nevada the nod. Sure, it had never built a functioning spacecraft, but few companies have, and Sierra Nevada has already sent lots of components—like batteries, hinges and slip rings—into space on more than 450 missions. Then there’s Dream Chaser’s design. A quarter of the length of the space shuttle, it promises to be the only spacecraft able to land on commercial runways and then fly again (up to 15 times in total) to the space station. And its ability to glide gently down to Earth ensures that precious scientific cargo, like protein crystals, plants and mice, won’t get tossed around and compromised on re-entry. That’s an advantage Sierra Nevada has over most other companies, whose capsules return to Earth by slamming into the ocean. Today, the only way the US can bring cargo back from space is via Musk’s SpaceX Dragon. “Quite frankly, that is why Nasa has us in this programme, because we can transport the science and nobody else can,” says John Roth, a vice president in the company’s space division.

Sierra Nevada has acquired its way into space. In December 2008, in the throes of the financial crisis, Sierra Nevada plunked down $38 million for a space upstart out of San Diego called SpaceDev. The company had recently lost a huge Nasa contract, its stock was trading for pennies and its founder, Jim Benson, a tech entrepreneur who became one of commercial spaceflight’s earliest prophets, had just died of a brain tumour.

Sierra Nevada had its eyes on a vehicle from SpaceDev called the Dream Chaser. It had a long, storied past: In 1982, an Australian P-3 spy plane snapped photos of the Russians fishing a spacecraft out of the middle of the Indian Ocean. The Australians passed the images on to American intelligence. It turned out to be a BOR-4, a Soviet space plane in which the lift is created by the body rather than the wings, making it suitable for space travel. Nasa created a copycat, the HL-20, and spent ten years testing it before pulling the plug.

Eleven months after the Columbia exploded, President George W Bush announced that the space shuttle programme would be shut down once the International Space Station was completed in 2010 (in fact, it took another year). In preparation Nasa invited companies to help supply the station. By this point Nasa’s HL-20 was mostly forgotten and gathering dust in a warehouse in Langley, Virginia. SpaceDev nabbed the rights to it in 2006, hoping to finally get it into space.

But it was an expensive job, and later that year Nasa declined to fund it. Enter Sierra Nevada Corp, which was always hunting for promising companies to buy. “The company had been very successful in defence but wanted to get into space and had a lot of cash,” says Scott Tibbitts, who sold his space-hardware company, Starsys Research, to SpaceDev in 2006.

Soon the Ozmens were devoting an outsize amount of time and money to the Dream Chaser. “It was very clear the space side was like a favourite son,” says one former employee. A decade after entering the space race, Eren and Fatih Ozmen, pictured at their home in Reno, Nevada, with their dachsund, Peanut, are finally approaching their first space mission in 2020 Eren Ozmen wears a Trinity necklace (on her wrist) by Coomi ($79,000). Eren Ozmen grew up in Diyarbakir, Turkey, a bustling city on the banks of the Tigris River, where she was a voracious reader and serious student. Her parents, both nurses, valued education and encouraged their four girls to focus on schoolwork. As a student at Ankara University, she worked full time at a bank while studying journalism and public relations and spent her little free time studying English.

A decade after entering the space race, Eren and Fatih Ozmen, pictured at their home in Reno, Nevada, with their dachsund, Peanut, are finally approaching their first space mission in 2020 Eren Ozmen wears a Trinity necklace (on her wrist) by Coomi ($79,000). Eren Ozmen grew up in Diyarbakir, Turkey, a bustling city on the banks of the Tigris River, where she was a voracious reader and serious student. Her parents, both nurses, valued education and encouraged their four girls to focus on schoolwork. As a student at Ankara University, she worked full time at a bank while studying journalism and public relations and spent her little free time studying English.

In 1980, as she was finishing her degree, she met Fatih Ozmen. A national cycling champion, he had just graduated from Ankara University with a degree in electrical engineering and planned to pursue his master’s degree at the University of Nevada at Reno. In 1981, Eren also headed to America, enrolling in an English-language programme at UC Berkeley. She reconnected with Fatih and, at his suggestion, applied to the MBA programme at UNR. After she arrived on campus, the two young Turks became best friends.

The pair soon struck a deal: Eren, a talented cook, would make Fatih homemade meals in exchange for some much-needed help in her statistics class. They shook hands and became roommates. They both insist they never even considered dating each other. “It was just like survival,” says Eren.

More like survival of the fittest. Eren knew she had to get top grades if she wanted a job in America. She was also broke and holding down several part-time jobs on campus, selling homemade baklava at a bakery and working as a night janitor cleaning the building of a local company called Sierra Nevada Corp.

After graduating in 1985 with her MBA, Eren got a job as a financial reporting manager at a midsize sprinkler company in Carson City, Nevada, just south of Reno. She arrived to find that financial reports took weeks to generate by hand. She had used personal computers in school and knew that automating the process would cut the turnaround time down to a matter of hours. She asked her boss if they could buy a PC, but the expensive purchase was vetoed. So Eren took her first paycheck and bought an HP computer and brought it to work. She started producing financial reports in hours, as she had predicted, and was promoted on the spot.

In 1988, the sprinkler company was sold, and Eren was laid off. Fatih, who was now her husband, had been working at Sierra Nevada since 1981, first as an intern and later as an engineer, and told her they were still doing financial reports by hand. She brought in her PC and automated its systems. Diagram by Chris Phipot for Forbes Soon after starting, Ozmen was sitting at her desk late one night and discovered that Sierra Nevada was on the verge of going out of business. The little defence company, which primarily made systems to help planes land on aircraft carriers, had assumed that its general and administrative expenses were 10 percent of revenues, but she calculated that they were 30 percent. At that rate, the business couldn’t keep operating for more than a few months. She marched to her boss’s office to deliver the bad news. He didn’t want to hear it, so she went straight to the owners. They were stymied. The bank wouldn’t lend them any more money. At Eren’s suggestion, the company stopped payroll for three months until the next contract kicked in. Employees had to borrow money to pay bills. “It was like the Titanic moment. We are waiting for this contract, but we didn’t know if we were going to make it or not,” says Eren.

Diagram by Chris Phipot for Forbes Soon after starting, Ozmen was sitting at her desk late one night and discovered that Sierra Nevada was on the verge of going out of business. The little defence company, which primarily made systems to help planes land on aircraft carriers, had assumed that its general and administrative expenses were 10 percent of revenues, but she calculated that they were 30 percent. At that rate, the business couldn’t keep operating for more than a few months. She marched to her boss’s office to deliver the bad news. He didn’t want to hear it, so she went straight to the owners. They were stymied. The bank wouldn’t lend them any more money. At Eren’s suggestion, the company stopped payroll for three months until the next contract kicked in. Employees had to borrow money to pay bills. “It was like the Titanic moment. We are waiting for this contract, but we didn’t know if we were going to make it or not,” says Eren.

That contract eventually came through, but Sierra Nevada was still living contract to contract two years later, when Eren, who was eight and a half months pregnant with her first child, got a call. The government audit agency had looked at the company’s books and declared the company bankrupt and therefore unfit for its latest contract. Eren got on the phone with the auditor (she remembers his name to this day) and told him he had made a math error. He soon responded that she was right and that he needed to brush up on his accounting skills but that the report was already out of his hands. At that point Eren went into labour. Less than a week later, she was back in the office with her newborn.

The company limped along until 1994, when the Ozmens borrowed against their home to buy Sierra Nevada. Eren was sick of working for an engineer-led company that was lurching from financial crisis to financial crisis and figured she and her husband could do a better job running the place.

It took five years for the company to stabilise, with Eren keeping a tight handle on costs. “I can tell you, it wasn’t a free-spending, freewheeling company. Everything was looked at,” recalls Tom Galligani, who worked at the company in the 1990s. Eren worked for a time as the company’s CFO and today is its chairwoman and president. Fatih became CEO and focussed on creating relationships with government agencies and developing new products. He also began looking for companies to acquire.

As the sun sinks over the Rockies, Eren sits by the window at Via Toscana, a white-tablecloth Italian restaurant outside Denver, sipping a glass of Merlot and explaining in rather unusual terms the couple’s approach to buying companies. “Our guys go hunting, and they bring me this giant bear, which is not fully dead, and say, ‘Now you do the skinning and clean it up,’&thinsp” she says. Fatih, sitting beside her, joins in: “There’s a lot of screaming. And blood.”

Fatih and his team search for companies that have some sort of promising high-tech product. Then they go in for the kill. “Of the 19 [companies we’ve acquired], we’ve never bought a company that was for sale,” he says.

“The first thing you do with the bear is to establish a trusting relationship,” Eren says, while reminding it of the benefits. “Every company we bought is ten times bigger now.” Over the years, Sierra Nevada has bought companies that do everything from unmanned-aerial-system technology to high-durability communications systems.

Its first acquisition was Advanced Countermeasure Systems, in 1998, which made equipment that helped protect soldiers from improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Revenues have since zoomed from $3 million a year to $60 million, Eren says. A company is especially attractive to Sierra Nevada if, like Advanced Countermeasure, it has so-called “sole-source” contracts with the military, meaning it is awarded contracts without a competitive bidding process, under the rationale that only that specific company’s product can meet the government’s requirements. Last year the majority of Sierra Nevada’s $1.3 billion in government contracts were sole-source.

Sierra Nevada’s biggest source of revenue is from aviation integration, which means folding new technologies into existing planes primarily at its dozen or so hangers in Centennial, Colorado. Often that entails stripping down commercial planes and turning them into jacked-up military ones, cutting holes to instal weaponry, cameras, sensors, navigation gear and communications systems. “What we do is take someone else’s airplane and make it better,” says Taco Gilbert, one of the many retired generals on Sierra Nevada’s payroll. For instance, it took the popular civilian PC-12 jet (“That a lot of doctors and lawyers fly around on,” Gilbert says) and modified it so that Afghan special-ops forces could pivot from surveilling the Taliban to conducting a medical evacuation in a matter of minutes. It sold the US Customs & Border Protection a fleet of super-quiet planes that can track the movement of drug traffickers without detection. When wildfires were raging in California in 2017, Sierra Nevada aircraft, modified with heat sensors, thermal imaging and night vision, provided support.

But it’s not just Sierra Nevada’s responsiveness that sets it apart it’s also its prices. In their own version of the “80/20” rule, the company strives to provide 80 percent of the solution at 20 percent of the cost and time. In other words, “good enough” is better than perfect, especially if “good enough” is cheap and fast. To deliver, Sierra Nevada spends 20 percent of its revenue on internal R&D, coming up with creative ways to upgrade the military’s ageing aircraft for less.

“This allows them to punch above their weight class and leapfrog the large guys,” says Peter Arment, an aerospace analyst at RW Baird.

“You can go to Boeing or Lockheed and take five or ten years and spend a lot of money,” Eren says. “Or we can provide you with something right now.”

On top of the $300 million it spent on the original Dream Chaser, Sierra Nevada has spent an additional $200 million so far on the cargo version and expects to invest $500 million more by the time it’s ready for take off. To recoup its costs, Sierra Nevada is counting on things going smoothly. The company has already earned $500 million in milestone payments from Nasa as it successfully completed design reviews as well as safety and test flights using the crewed Dream Chaser (which shares 80 percent of the same design and features) before it was retired. Much like when Eren was counting on that key government contract to cover payroll in 1989, Sierra Nevada is now waiting for the big payoff that will come when it sends the vehicle into space. Its launch date is set for September 2020, 11 months after rival Orbital ATK’s Cygnus takes off in October 2019 and a month later than SpaceX’s Dragon 2. If the Dream Chaser completes its six missions to the space station by 2024, Sierra Nevada will pocket an estimated $1.8 billion.

Eren isn’t blind to the risk that things could go wrong. But brimming with an immigrant’s sense of patriotism, she talks of the glory of helping the US re-establish its leadership in space. She thinks Sierra Nevada and other private companies can help the government catch up on the cheap. “Looking at what are the things we can do to make space available,” Eren says, “it’s the commercial companies who are going to come up with those creative ideas and help the country catch up.”

First Published: Aug 10, 2018, 11:28

Subscribe Now