Steve Anderson: The one-man deal machine

Steve Anderson paints his toenails blue and works alone out of a former children's photo studio. By filling the gap between angels and big firms, he's also become the second-best venture capitalist in

After yet another 12-hour day of coding, Kevin Systrom’s nerves were frayed. It was June 2010, and he had spent seven months working on a Foursquare-like social check-in app that was going absolutely nowhere. Desperate, he and his co-founder, Mike Krieger, decided to chuck the app and make a photo-sharing tool instead. Now they had to convince their founding investor—a guy named Steve Anderson, who wrote their first cheque for $250,000 four months earlier. The young entrepreneurs slumped across the street into the appropriately named Crossroads Cafe, a cheapo San Francisco establishment staffed by ex-convicts.

Anderson knew the numbers were bad. They’d been talking about it for weeks. The young founders told him their plan to start fresh, not sure if their backer would be irate, disappointed or sympathetic. Anderson rubbed the ginger stubble on his chin and stared at the table. It didn’t take him long, however, to look up with a grin: “Well, what the hell took you so long?”

A billion dollars later, Instagram’s co-founders can laugh about that meeting, but Anderson’s facetious question told Systrom and Krieger all they needed to know. “I meet too many people who care too much about money in the Valley,” says Systrom. “I never felt like Steve was ever worried that we were going to screw up. He may have been worried, but he showed confidence.”

That kind of split-second verdict is typical Anderson, the 47-year-old brain behind one of Silicon Valley’s most successful—and smallest—investment firms. As the second-highest-ranking member on the Midas List, Forbes’s annual tally of the world’s top 100 tech investors, he could easily join an elite VC firm. But his Baseline Ventures has only one decisionmaker, with an uncanny ability to find and fund entrepreneurs with germs of possibly big ideas. Instagram, of which his fund owned 12 percent when Facebook acquired it for $1 billion, put Anderson on the radar, coupled with other massive scores like Twitter and Heroku, which sold to Salesforce for about $250 million in 2010. His next crop of potential exits looks just as promising and includes fintech firm Social Finance (valued at $4 billion), women’s fashion phenomenon Stitch Fix (on its way to unicorn status) and multiplayer-game publisher Machine Zone, the company behind Game of War (reportedly raising funds at a valuation of at least $6 billion). With a net worth Forbes figures is at least $150 million, why work for—or with—anyone else?

To underscore his lone-wolf status, Anderson has exiled himself from San Francisco’s financial district and the VC mafiosi on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, California, cutting a dozen deals a year out of a former children’s photography studio in San Francisco’s Cow Hollow, a neighbourhood better known for brunch and Bikram yoga than for tech talent. “Someone once asked me, ‘How do you do 10 or 12 deals a year?’&thinsp” says Anderson. “I said, ‘Remember the next time you’re in a Monday morning partner meeting talking about deals that your partner wants to do or when you’re bickering in your office about the politics of the firm. All that time I’m just meeting with companies.’&thinsp”

Anderson says the one-man-band thing is more about freedom than ego. He can sign a $500,000 cheque within 30 minutes of meeting a founder without consulting another soul. He blasts electronic dance music while fielding calls and meets with suit-and-tie investors in a hoodie and jeans. He paints his toenails blue when he dances at raves. He’ll skip to Las Vegas on a Thursday to party with DJs like Deadmau5 and Kaskade a few times a year or disappear for three days on a solo bike ride to Lake Tahoe, an annual tradition. He’s earned this right with his stunning returns. Anderson turned $70 million raised across his first three funds into $700 million and says he has written off only one-fourth of his portfolio companies, an enviable batting average. Twenty of his deals have had exits of more than $100 million. “My partnership meetings are really short,” he says. “Me, myself and I have a long debate.”

Baseline’s emergence in 2006 helped pioneer a new category in venture: Investments that lie between the $25,000 angel-stage sums often raised from wealthy individuals and the $1 million or more that usually came from traditional VC firms in the so-called Series A round. Baseline’s $250,000 to $1 million cheques take anywhere from a 5 percent to a 15 percent stake while giving founders a year to 18 months to develop a product with minimal pressure. Anderson has remained true to that approach, even if that’s led to some painful misses. Anderson bowed out of joining Dropbox’s seed round when its founders raised the price by just a couple million. He also whiffed badly on Uber (twice), even after Travis Kalanick stood in his office, gesticulated wildly and explained how he as CEO would kill the taxi industry. “I just couldn’t see past black cars,” Anderson says.

The startups he picks, though, gain a valuable ally. Weebly CEO David Rusenko calls him the “best investor you could hope for”, one who coached him weekly on hiring and dealing with corporate clients in the early years. SoFi CEO Mike Cagney says that without Anderson his company wouldn’t be alive, as the investor stepped up to lead a $80 million round after SoftBank had backed out of an earlier $100 million commitment in the summer of 2012. SoFi had counted on that money and approved some $60 million worth of loans with no underlying backing if the financing fell through. “He didn’t use his position to extract a lot of bad stuff when he had a lot of leverage because we needed a deal done,” says Cagney. Fellow investor and friend Chris Sacca puts it more bluntly: “This can be a nasty business, and people get screwed over all the time, but you’re never going to get Steve to say a harsh word about anybody.”

Steve Anderson’s roundabout way to Silicon Valley began in a double-wide trailer parked in his grandparents’ backyard in the Seattle exurb of Issaquah. He and his sister lived there with a single mom (his father had abandoned the family when Anderson was 5 Anderson never got to see him before he died). His mom was a secretary—at times the family lived on food stamps—so Anderson took to menial jobs. He was a paperboy, a dishwasher, a jeans model, an Alaska cruise tour director and one half of a travelling DJ duo.

With the mentorship of a surrogate father that he found through a United Way Big Brothers programme, Anderson got into the University of Washington, where he studied physics and business. His mom wanted him to be a Boeing engineer. That didn’t pan out—Anderson’s moneymaking extracurriculars turned him into a B student. He tried selling minicomputers but became obsessed with an idea he had for Starbucks. He approached Howard Behar, the father of one of his college fraternity brothers and Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz’s right-hand man, with a plan to sell beverages via coffee carts. Behar appreciated the enthusiasm and offered Anderson a job as a store manager. Within four years, Anderson had become a general manager for the Seattle region.

Anderson got into Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and moved down to Palo Alto in 1997. That summer, he took a product-management internship at a blossoming online marketplace called eBay and earned himself a job offer. Though eBay was about to go public, he consulted with then-CEO Meg Whitman and eventually declined the offer in order to return to school, missing out on the opportunity to become an overnight millionaire. He’d have to start the process all over again after graduation at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, where partner John Doerr had been angling to hire him.

He arrived at KPCB in the dotcom spring of 1999, when the firm was at its peak. Its partners sat on the boards of powerful companies such as AOL and Compaq. Anderson was initially paired with Doerr, who had just scored with the Amazon.com IPO. One of his first jobs was to put paperwork together for a deal with two Stanford computer science students who had a startup with no immediate plans to make money, only an ingenious way to change online search. “With Google, I asked John, ‘Where is the spreadsheet that justifies this investment?’&thinsp” says Anderson. “This is more art than spreadsheet,” he recalls Doerr saying. Kleiner ended up investing about $12.5 million at a $99 million valuation.

Though Anderson was an unlikely hire for Kleiner Perkins, he quickly made an impression on the veterans. Former Oracle president Ray Lane, who joined the firm in 2000, recalls that he was “better at diligence than others” because CEOs opened up to him. Anderson’s legwork helped the firm avoid a disastrous investment in last-minute-delivery firm Kozmo, which eventually went belly-up. “Our buddies at Amazon did invest at the time,” says Doerr, who was originally set on the idea. “He was with us through the start of the boom, and he also saw the worst of times.”

Kleiner provided a solid foundation, but, like many venture firms of the period, it wasn’t designed to promote from within. “The programme was, you’ll work here and get experience, but you probably can’t stay,” says Aileen Lee, a fellow associate partner who has since founded Cowboy Ventures. Told investors needed more operating experience inside a big tech company in order to make partner, Anderson considered stalwarts like Cisco and Salesforce before accepting a gig as a senior marketing director at Microsoft. “Steve always had a really good personal true north,” says Lee. “He’s not bothered or distracted by what seems attractive to other people.”

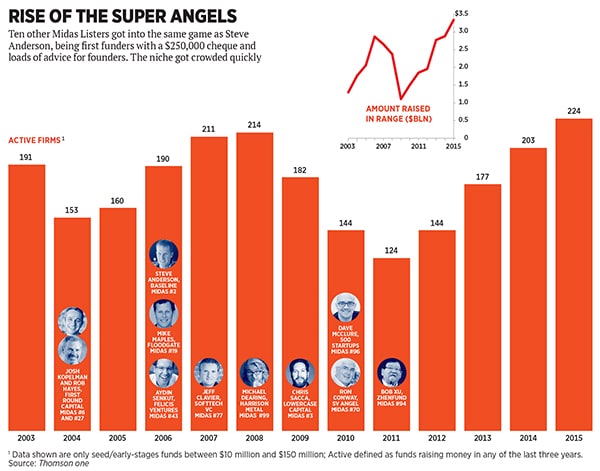

Anderson didn’t stay away for long. He left Seattle to return to the Valley in early 2006 with the stock market in full recovery and talent flooding back into tech. Mobile was a new continent to colonise, and Amazon had just begun renting cheap access to its vast computing infrastructure to startups, eliminating an expensive hurdle for them. Anderson persuaded a couple of Microsoft buddies to defect and start their own cybersecurity firm that he would invest in, but he couldn’t find any other VCs willing to kick in the kind of money he wanted, a first cheque of $250,000 or so. Wealthy individuals were still happy to put in a few thousand dollars each, but the number of institutional funds of $150 million or less, the kind most willing to invest a single dose like that, had dropped from 178 at the peak of the dotcom bubble in 2000 to just 55 in 2004, according to Thomson Reuters.

Jettisoning the cybersecurity play, Anderson decided instead to exploit this gap and raise a fund of his own from which he would write cheques for $250,000 or so at a time, more than an individual “angel” would want to risk but too small for a VC firm with $500 million in funds to manage. The big VC firms such as Kleiner or Sequoia rely on multibillion-dollar exits to generate their hoped-for eight or 10 times returns on $10 million to $50 million investments. Anderson could make a similar-size return hitting doubles and singles, as long as he could get into good startups early. “I started Baseline with the idea that I’m playing for the $100 million outcome,” says Anderson. “And if you get a couple of the big ones, your returns will go through the roof.”

This new class of “super angels” were no hobbyists. They had real operating experience and could open doors at big tech companies. The old guard called it a fad and criticised super angels over the size of their investments. “My partner Rob [Hayes] would get told, ‘Isn’t that cute?’&thinsp” says Josh Kopelman, who’d exited three startups before founding First Round Capital. “We were the outside kids, the rebels,” says Aydin Senkut, a Google veteran who launched Felicis Ventures.

By the late spring of 2006, Anderson had his pitch deck ready to present to potential limited partners but lacked one big thing: Deal flow. One of the first people he called was Ron Conway, a legendary angel investor who saw most ideas that came along. He backed Google and PayPal and had been a mentor from Anderson’s Kleiner days. Conway, who had taken a break from active investing, obliged. He was a key investor in Baseline Ventures’ first fund and introduced Anderson to Ev Williams and Jack Dorsey of Twitter, which became a big win for the firm. Conway also brought Anderson two eventual staffers, David Lee and Brian Pokorny, to help with sifting through ideas. Without much of a reputation, Baseline struggled to raise its first $10 million fund. Things got easier after it had its first quick score, selling portfolio company Parakey to Facebook. This was Mark Zuckerberg’s first acquisition, and Baseline had seeded Parakey only a year earlier.

But as Anderson’s stature increased, his partnership with Conway began to fray over a disagreement on investing philosophy. Conway was getting excited about social media and wanted to focus on it the same way he’d found his earlier big wins—backing dozens of fledgling firms at once and doubling down as winners emerge. Anderson typically backed 10 companies a year, a much slower pace, across lots of categories. “Steve wanted to stay true to his approach,” says Lee. They decided to part ways, with Conway taking Lee and Pokorny to start a new firm, SV Angel.

The irony: Conway went off to focus on social media but missed Baseline’s greatest social media play ever. Anderson, fresh from raising a new $55 million fund in the depths of the recession, seeded Instagram’s Systrom in February 2010. By April 2012, his photo app was a clear winner, and Zuckerberg was constantly messaging Systrom with overtures to join the Facebook empire. Anderson told his young CEO to be wary: Instagram had the potential to be at least a $5 billion company. But Systrom wanted to do a deal at roughly $1 billion in cash and stock. Anderson could have blocked the deal as a director, but he never even threatened to undermine what his CEO wanted. “Even at the number we sold at, that was life-changing,” says Anderson. “I didn’t invest to maximise my return. I invested because I believed in Kevin.”

On a drizzly Monday in March, three more entrepreneurs have made the trek to Cow Hollow. Anderson has set the day aside for investor meetings, but he’s been able to slot in a few minutes for founders who need some coaching. He so zealously guards his time that his assistant will interrupt every meeting with 10 minutes left to ensure he doesn’t run over. When the entrepreneurs from small business scheduling software company Homebase go over their latest numbers and wonder aloud why customer sign-ups have slowed down, Anderson looks at the stats before giving simple advice: Let’s hire an internal PR person to generate buzz, he says, and they nod. In an earlier meeting, Sidharth Kakkar, the CEO of educational technology company Front Row, asks Anderson for the best way to fire inefficient workers and streamline the teams reporting to him. After a small discussion, Anderson takes to his whiteboard and diagrams a new way to assign people into groups.

No matter how successful startups become, they always have a crisis or ten. In late 2012, Stitch Fix CEO Katrina Lake was getting perilously close to not making payroll and had been turned down by 20 venture firms. Anderson, who had written her first cheque, told her to take a vacation over Christmas and gave her $250,000 more to keep the business afloat. Earlier this year, Manik Singh, the CEO of Threadflip, a used-clothing marketplace that had raised $22 million, came to Anderson to tell him he was shutting down. Anderson, an investor in Threadflip, said do it. “ ‘You’re not working for me so I can have some large exit,’&thinsp” Singh recalls Anderson telling him. Threadflip’s closure wiped out millions of dollars in capital, including approximately $1 million from Anderson. Of such situations, Anderson shrugs. “I don’t want them feeling they’re working for me to get back 10 cents on the dollar,” he says. “I’m a big boy, and I’m in this business to lose money, too.”

Anderson has made a lot of money for his backers because there have been more Stitch Fixes than Threadflips. The startup economy has gotten far tighter lately, and Anderson is prepping his companies for another correction, the third of his career. “I’m not sure if it’s going to be a bloodbath or just some heavy vein bleeding,” he says. He made only two investments in the last quarter of 2015—a sign of being even more choosy. If there is an even bigger crash in early-stage funding, Anderson says he is open to changing his playbook to invest beyond the seed stage.

There’s also nothing stopping Anderson from walking away. He’s already made a fortune and doesn’t have anyone to answer to. “My ego doesn’t say Baseline has to live on beyond my interest in it,” he says. “I don’t have that need to build an institution.” He’s giving up the Cow Hollow place. Rents are too high, so he’s going to set up in cheaper digs at a co-working space downtown.

For now, Anderson is having too much fun to slow down. At this story’s photo shoot, he gleefully goes along with the photographer’s idea to cover his hands in gold paint, a not-so-subtle metaphor for his rank on the Midas List. After modelling for the better part of three hours, Anderson goes off to clean up before a phone call with an entrepreneur. The soap and hot water slowly wash away the gold sheen from Anderson’s freckled hands. Is it a sign?

“I damn well hope not,” he says with a smile.

First Published: Apr 28, 2016, 06:09

Subscribe Now