The Cannes Lions advertising festival has become as big among the Madison Avenue crowd as the Riviera town’s iconic film event is for Hollywood. So as Steve Stoute nursed a drink with a friend at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc on the balmy June evening that opened this year’s boozing and schmoozing, the Cannes Lions veteran braced himself for an onslaught of media and technology executives. Stoute’s ad agency, Translation LLC, has clients like Anheuser-Busch, State Farm and McDonald’s—the kinds of whales that would have him fending off supplicants left and right.

But the roles of supplicant and master reversed when Stoute spotted Ben Silbermann walking into the bar. The soft-spoken Pinterest CEO was attending Cannes for the first time. Silbermann, 32, had just checked into his hotel and was planning to have a quick drink with his team before turning in to prep for his keynote speech the following morning. A few weeks earlier, his social media service began experimenting with selling ads to show to its 70 million users. With more demand than it could satisfy, Pinterest had limited its test to a mere dozen sponsors, wringing commitments of more than $1 million from each.

Stoute was desperate to get his newest client, discount shoe store chain DSW, into the programme (fashion is the third-most popular type of content on Pinterest). “I didn’t want this thing to go by without us getting in front of it,” he says.

Stoute’s drinking buddy that night was Ben Horowitz, whose venture capital firm, Andreessen Horowitz, had just participated in the $200 million funding round that had propelled Pinterest’s on-paper valuation to $5 billion. Horowitz called Silbermann over, and Stoute ordered rosé for everyone, raised his glass toward his new acquaintance and offered a paean of praise and blessings: Rise above, be great, stay great.

After accepting Stoute’s flattery, Silbermann agreed to take his money, too. An hour into his Riviera debut, the new prince of Cannes had already bagged his first deal, just by showing up.

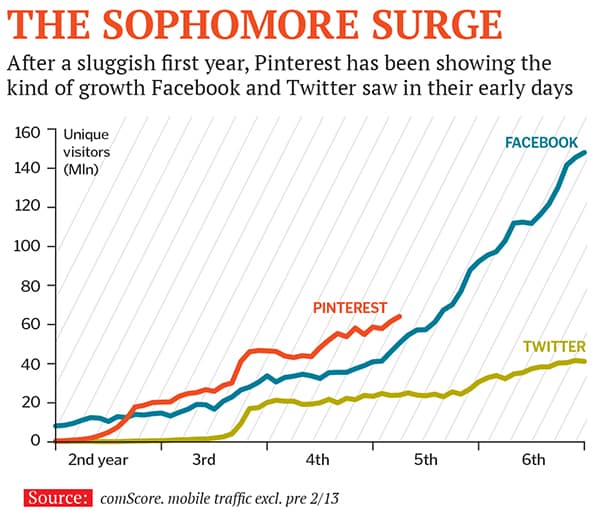

That’s pretty much how things have been going for Pinterest lately. A visual social network where people create and share image collections of recipes, hairstyles, baby furniture and just about anything else on their phones or computers, Pinterest isn’t yet five, but among women, who make up over 80 percent of its users, it’s already more popular than Twitter, which has a market capitalisation of more than $30 billion. Pinterest’s US user base is projected to top 40 million this year, putting it in a league with both Twitter and Instagram domestically, and it’s moving fast to catch up with them overseas, opening offices in London, Paris, Berlin and Tokyo over the past year. International users now make up nearly half of new sign-ups, according to research firm Semiocast. Pinterest even doubled the number of active male users in the past year.

To date, Pinterest’s users have created more than 750 million boards made up of more than 30 billion individual pins, with 54 million new ones added each day. During the 2013 holiday season, Pinterest accounted for nearly a quarter of all social sharing activity. Among social networks, only Facebook, with its 1.3 billion users, drives more traffic to web publishers.

All that activity sounds big, but it understates the money-making opportunity in front of Pinterest. While it’s the earliest of days still, many analysts believe that, on the basis of average revenue per user, it’s only a matter of time before Pinterest blows past Facebook, Twitter and the rest of the social pack. “It’s going to bring in billions of dollars a year,” says Dave Weinberg, founder of the social marketing company, Loop88.

To marketers, Pinterest represents a unique proposition, a new medium of a sort that’s never existed before. One difference is temporal. As Silbermann explains it, Facebook “is about your connections, your past events, your memories”. Users on Facebook volunteer a staggering amount of retrospective information such as birthplace, alma mater and vacations, data the company can use to power its highly targeted ad offerings. Twitter can’t offer that level of detail, which is why its revenue per user, at around $3.50, is only half that of Facebook’s. Twitter’s value remains stuck in the now, promising advertisers a presence in real-time conversations about the World Cup, a presidential election or Orange Is the New Black.

If Facebook is selling the past and Twitter the present, Pinterest is offering the future. “It’s about what you aspire to do, what you want to do,” says Silbermann. And the future is where marketers want to live. When a user pins an image of a wedding dress or a coffee table to one of her boards, she’s sending up a signal to the merchandiser who might want to sell her that dress or coffee table. “There’s intent around a pin,” says Joanne Bradford, Pinterest’s head of partnerships. “It says, ‘I’m organising this into a place in my life,’ like when people tear out a page of a magazine.”

The idea of being able to locate consumers at that delicate moment when browsing becomes shopping has marketers intrigued. “One of the things we’re trying to figure out strategically is how to tap into consumers earlier in the inspiration or planning phase,” says David Doctorow, senior vice president of global marketing at Expedia, one of Pinterest’s charter advertisers.

For now, advertising is Pinterest’s only revenue line. But it requires only the tiniest leap to conjure a scenario in which the company acts as middleman for the hundreds of thousands of retailers already showcasing their wares on its platform. “The next step will be how do we make it really easy for you to go out and buy that ring or take that trip,” says Silbermann. This is Amazon’s turf, but Facebook and Twitter have been making incursions, with both companies conducting tests of “Buy” buttons for frictionless shopping. Pinterest, though, has natural advantages in ecommerce, with independent research showing its users are more likely to share product links and make big purchases than users of other social platforms.

If Pinterest is going to lay claim to the future, it will have to knock off a pretty formidable incumbent, Google, which is also in the business of harvesting signals of intent and selling them to marketers. That’s the basis of its search advertising, the engine that drives roughly two-thirds of the company’s $55 billion in annual revenue.

Silbermann, who spent two years as a product specialist in Google’s advertising operation, knows what he’s up against. For all his Midwestern diffidence, he’s not shying away from the confrontation. In his Cannes keynote, Silbermann dismissed Google as “the ultimate card catalogue,” an outdated technology useful only if you already know what you’re looking for. Evan Sharp, Silbermann’s co-founder, puts a finer point on it. Pinterest, he says, “exposes people to possibilities they never would have known existed”.

Pinterest people talk of this open-ended form of search as discovery, and figuring out how to do it right “is the biggest business opportunity in the last 10 to 20 years for an online business,” says Tim Kendall, Pinterest’s product head. The choice of time frame is not accidental: As Facebook’s director of monetisation from 2006 through 2010, he shaped the strategy that turned that company into the $200 billion force it has become. He says Pinterest will be bigger—bigger than Facebook and, yes, bigger than Google. “That’s why I joined.”

Silbermann didn’t always know what he was looking for. As a child in Iowa, he had multiple collections, including one of dried insects pinned to cardboard as an adult, he started a pinning site for virtual collectors whose most avid early users were in the Midwest.

But the path was nowhere near as straight as that sounds. Silbermann grew up thinking he’d be a doctor like his parents, who are ophthalmologists. An accomplished cellist and debater, he spent the summer before his senior year in high school at MIT’s elite Research Science Institute and then enrolled at Yale, where he took pre-med courses. Halfway through college, though, he caught the business bug. Instead of taking the MCAT upon graduation, he took a job as a management consultant at the Corporate Executive Board in Washington, DC. “I just wanted a job at the beginning,” he says of taking the road more travelled.

He quickly grew restless, growing increasingly fascinated by what was going on in the technology industry. “I would read blogs on it in my free time and think, ‘What am I doing?’ The story of my time, this thing that I’m super-excited about, was happening in California, and I was like, ‘I’ve got to get out there’,” he recalls. After three years as a consultant, he scored “the only job I could get at Google,” as a product specialist, and moved out West in 2006. Silbermann spent his days translating customer feedback into product refinements, acquiring a skill he considers crucial to Pinterest’s success. But troubleshooting ad systems wasn’t what he’d come to do. Silbermann decided to quit and try to start his own company.

![mg_78223_social_media_280x210.jpg mg_78223_social_media_280x210.jpg]()

He hooked up with a Yale classmate, Paul Sciarra, and in 2008, the two started Cold Brew Labs. Its first product was a shopping app called Tote, which struggled to stir up interest. Silbermann was visiting New York when he met a mutual friend, a Columbia architecture student named Evan Sharp. “We both had the same hobby, which was the internet,” Sharp says. “For both of us, in a way, the internet was this really precious window into worlds outside our day-to-day experience.”

Sharp told Silbermann about his collection of thousands of architectural drawings and photos, which had become increasingly hard to organise. That resonated with Silbermann, who’d noticed that Tote’s users seemed more interested in saving photos of products than in buying the products themselves. He invited Sharp to join Cold Brew Labs, and together, the three launched the first desktop version of Pinterest in March 2010. Users could save images from anywhere on the web to thematically organised boards—“Nail Art”, “Honeymoon Ideas”, “Viking Designs” and so on—as well as follow other users and their boards.

Every section was a free-form grid that scrolled in a never-ending succession of pictures and words. As the work progressed, Sharp moved to the Bay Area and took a job at Facebook to support himself while the three worked from their makeshift offices, a “dirty apartment” in Palo Alto.

This is the point where usually the founders hit on the novelty that makes their product go viral overnight. That wasn’t how it happened with Pinterest. Its early gains were the result of laborious word-of-mouth marketing, with Silbermann leaning on everyone in his network to spread the word and personally contacting several thousand users to quiz them about what they liked and disliked. “If he hadn’t done that, my guess is we would’ve given up in a few more months,” says Sharp, 31. “It’s kind of ridiculous how long we worked on it, given how little success we were seeing.”

Nor was it an overnight sensation with investors. “He had a hell of a time raising money in the beginning,” says Ron Conway, a perpetual member of the Forbes Midas List, whose firm, SV Angel, invested in April 2011 at the urging of fellow angel Shana Fisher. Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman was one of those who failed to see the potential. “A friend sent it to me and I didn’t even take the meeting,” he recalls. “I was like, ‘Ehhhh, this is interesting, but I don’t know what to do with it. It’s too conceptual for me’.” (Fortunately for Stoppelman, the opportunity came back around a year later, courtesy Eventbrite CEO Kevin Hartz, whose enthusiasm for Pinterest won him over.)

Those days are past. To date, Pinterest has raised $764 million in seven rounds from a group of investors that includes FirstMark Capital, Andreessen Horowitz and Bessemer Venture Partners. In May, it closed that blockbuster $200 million round that provided fuel for its international expansion. At that valuation—and given the mania for fast-growth companies over the ensuing six months, a raise in the range of $8 billion to $10 billion is possible—Silbermann’s estimated 15 percent stake and Sharp’s estimated 10 percent would make them, on paper, candidates for the Forbes billionaires list.

Others are jumping on the gravy train. With more than 400 employees—up from fewer than 20 in early 2012—Pinterest has just signed a lease on another building in the neighbourhood. “I spend a lot more of my time trying to clearly communicate where we’re going so everyone can march in the same direction,” Silbermann says. “Technology has made it easier for small teams to scale fast, but no one’s ever released something that makes it easy to build a culture proportionately as fast.”

The cornerstone of Pinterest’s culture is a principle they call Knit. Whereas other big tech companies in the Valley are led by people of one skill set—engineers at Google, designers at Apple—Pinterest solves problems by combining different kinds of expertise. “That way you can produce something that no one individual with one expertise could have produced on their own,” says product chief Kendall. “We’re trying to build a culture of deep appreciation for different disciplines,” Sharp says.

Despite their similarities, Silbermann and Sharp have slipped into complementary roles. (Sciarra, the third co-founder, left Pinterest in April 2012, finding a soft landing as an entrepreneur-in-residence at Andreessen Horowitz. “Ben was the guy to take the company into its next phase, and he’s doing an excellent job,” he says.) The linear-minded, strategic former management consultant was the natural choice for CEO. No rah-rah motivator, he spent a recent evening diagramming the company’s internal communications channels on a whiteboard to figure out which ones were working best. Sharp, a more lateral thinker, became chief creative officer. “I’m a little more crazy than Ben is and a little more—I don’t want to say artistic but a little more on the creative side,” Sharp says. “My mind is like a warren, whereas Ben’s is like a f--king database.”

![mg_78225_pinterest_280x210.jpg mg_78225_pinterest_280x210.jpg]()

Sharp sometimes feels bemused by the speed of all the change around him. “It’s something you don’t hear a lot about necessarily, but it’s a very weird process to grow up with the company but not to be the face of it as much,” he says. “It can make you feel insecure. I feel great, but I could see how a lot of co-founders end up spinning out or burning out of companies that they aren’t the CEO of, because you have to really be confident that you’re contributing.”

In a conference room in Bellevue, Washington, a crew of Pinterest ambassadors tutor executives from Expedia in the art of pinning. Larkin Brown, a chic, willowy user-experience researcher, explains how the different reasons users pin things—to plan a project, to compare different styles or just for inspiration—correspond to the phases of the so-called purchase funnel: Awareness, consideration, preference and purchase. “The thing that’s important to understand is it’s the pin that triggers the mode,” says Brown. She hands over the PowerPoint clicker to Kevin Knight, head of agency and brand marketing, who stresses that every board a brand creates ought to correspond to an interest someone might have, since that’s how users organise their own boards. “Patio furniture isn’t an interest outdoor living is an interest,” he says. Around the table, heads nod and pens scribble. In 2013, Expedia spent more than $1.7 billion on advertising and marketing across its brands, which include Expedia.com, Hotels.com and Trivago.

Pinterest conducts these five-hour workshops for the dozen or so partners in its Promoted Pins programme—i.e., its advertising clients who have committed $1-$2 million for a six-month run. After a workshop, participants typically see the interaction rate on their pins increase by 25 percent. Making sure advertisers know what they’re doing before they start spending money ensures they’ll be happy with the result, says Bradford, who oversees sales. They’d best be happy, since charter advertisers are reportedly paying $30 to $40 per thousand impressions—several times the rate Facebook commands.

Like Facebook’s Sponsored Posts and Twitter’s Promoted Tweets, Promoted Pins are a form of so-called native advertising, in which an ad takes the same form as the user-generated content around it. Native advertising evolved in response to what marketers call “banner blindness”, the tendency of web users to tune out adjacent ads. It’s also turned out to be perfect for mobile phone screens, where ads must appear in the main feed or not at all. More than 90 percent of Pinterest usage is on mobile, higher than Facebook (68 percent) and Twitter (86 percent), according to comScore.

But there’s native and then there’s native. Facebook may know you’re a Cleveland Browns fan who takes a size XL, but when it shows you an ad for a Dawg Pound sweatshirt in your News Feed, it’s an unwanted interruption because who goes on Facebook looking to buy a sweatshirt? Pinterest users, on the other hand, are very much in the mode of planning how to spend their money. If you’re browsing for beach vacation ideas, an Expedia pin showing all-inclusives in Cancún isn’t an intrusion—it’s just more information. “Pinterest is a place people come to discover things they love,” says the firm’s head of operations, Don Faul, a veteran of both Facebook and Google. “Brands are at the centre of that.” To make sure its ads never feel too much like ads, Pinterest has a few ground rules: Every Promoted Pin has to start out as an ordinary pin, living on the partner’s boards, and stunts like price promotions and contests are off-limits.

For high-end marketers, context is everything. Yahoo’s Marissa Mayer calls it the “Vogue phenomenon”, alluding to the way glossy magazine ads seem like they’re part of the experience, while online ads are always a nuisance. Yahoo’s $1 billion acquisition of Tumblr, another visual social network, was Mayer’s attempt to recreate the phenomenon in pixels Pinterest, with a bigger, more focussed audience, has a better shot.

“With Pinterest, at least people have shown some intention to be served the content you’re providing them,” says Meghan Burns, marketing director for Vineyard Vines. “As a luxury brand, it’s a huge step in the right direction. We can buy impressions all day long, but it’s all about maintaining a positive association with the brand.”

Pinterest provides a suite of tools to help brands quantify the return on their time and dollars and is collaborating with them to develop new ones tailored to their needs. Burns says her company’s web traffic and new user numbers are up since it started paying to promote pins, and its non-paid pins are also performing better on measures of audience reach and engagement. While one analysis of data from 25,000 retailers showed that users driven to commerce sites from Pinterest are 10 percent likelier to buy something than those coming from other social sites, Burns wants more convincing proof that the brand’s Pinterest fans are converting into sales. “I’m really waiting for that second tier of data to say, ‘Shoppers are ready to buy here’,” she says.

Once that happens, why not just sell to them directly? Ecommerce is clearly part of Pinterest’s road map, but even with that war chest, it is still in ramp-up mode. Its workforce remains one-eighth the size of Twitter’s, much less Facebook’s or Google’s, which still means doing things one at a time, even if it means letting rivals get a head start.

That doesn’t bother Silbermann and Sharp. They’re not focussed on selling stuff to their users any more than Silbermann was thinking about selling ads when he walked into Hôtel du Cap.

The opportunity is much bigger. “How do we do for discovery what Google did for search?” Silbermann muses. “How do we show you the things you’re going to love even if you didn’t know what you were looking for? We think if we answer that question, all the other parts of the business will follow.”