On March 25, 2016, Sarah Fuller, 32, was supposed to drop off her mother’s car at the shop. Her mom called at 8 am to make sure her daughter was up. She got Sarah’s fiancé. He found Sarah in her room, motionless, with her face on the floor. She was dead. The medical examiner implicated two drugs Sarah had been prescribed: Xanax, for anxiety, and Subsys, the fastest-acting form of fentanyl, among the most potent narcotics known to medicine. The combination was dangerous, but Sarah’s family blames Subsys and its maker, Insys Therapeutics, for her death and plans to sue. “They obviously had no regard for human life,” says Debbie Fuller, Sarah’s mother. “In order for them to make the bottomline bigger, people have to die for it.”

Subsys is the brainchild of John Kapoor, 73, one of the most successful pharmaceutical entrepreneurs in America and the founder, chairman and chief executive of Insys. Kapoor is worth $2.1 billion, and his Insys shares represent $650 million of his net worth. The company’s stock is up by 296 percent since its 2013 IPO.

His idea for what became Subsys was to pair fentanyl, a narcotic 80 times more potent than morphine, with spray technology that would allow patients to get a dose under their tongues. The point was to ease cancer-related pain, which often breaks through high doses of existing opioids. It’s a subject Kapoor knows well: Editha, his wife of three decades, died of metastatic breast cancer in 2005.

“I was a caregiver for her,” Kapoor says. “I took care of her. I saw what she had to go through, and I can tell you, pain is such a misunderstood thing for cancer patients. Nobody understands pain. They think pain is just pain. My wife went through it.”

But critics allege that Insys sales reached $331 million last year because the drug is also being used for patients who do not have cancer. Like Sarah Fuller. She suffered from back and neck injuries from two car accidents a decade ago and from fibromyalgia, a mysterious disorder that causes diffuse muscle and bone pain. Kapoor is quick to say that it “doesn’t make sense” to give a fibromyalgia patient Subsys, a drug designed to relieve sudden spikes of excruciating pain. (Insys did not comment directly on Fuller’s death.) More than that, it would be illegal for Insys to promote the drug for such use, because the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Subsys only for cancer patients.

Yet, in 2015, a nurse practitioner in Connecticut pleaded guilty to violating a federal anti-kickback statute by taking money from Insys to prescribe the drug to Medicare patients who did not have cancer. A former Insys sales representative in Alabama also pleaded guilty to a conspiracy to violate the anti-kickback statute by paying two doctors to prescribe the drug. Illinois has filed claims against Insys related to pushing Subsys for unapproved uses. US attorneys in two jurisdictions—the Central District of California and the District of Massachusetts—are investigating the company. Doctors who have worked with the company are being investigated by Michigan, Florida, Kansas, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and New York.

One case has been settled: Insys paid the state of Oregon $1.1 million, a small amount for the company but twice its entire book of business in the state, to settle charges that it was working to persuade doctors to prescribe Subsys to patients who did not have cancer. To date, Insys has admitted no wrongdoing and says it has strengthened its procedures to prevent lapses from occurring in the future.

It’s familiar territory for Kapoor. He has made a habit of founding companies and allowing them to push legal and ethical limits, confident of his ability to clean up the resulting mess. Insys is just the latest chapter.

“My involvement is I am an investor,” Kapoor says. “As an investor I’m on a board. As a board member and an investor, you are involved, but you are not involved in day-to-day operations, and that’s where the problems come in.”

![mg_89477_john_kapoor_280x210.jpg mg_89477_john_kapoor_280x210.jpg]()

Kapoor grew up modestly in India. He was the first in his family to attend college. He earned a doctorate in medicinal chemistry from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1972 and quickly went to work in the corporate world. “In India they teach you how to work in a factory,” he says. “They don’t teach you how to work in a drugstore.”

In the 1970s, many companies had small divisions that made generic drugs. Kapoor started at Invenex Laboratories, in Grand Island, New York, which was owned by Mogul Corp, a water treatment firm. He worked there for six years (he met his wife there), but he wanted to run something on his own. In 1978, he says, he approached LyphoMed, a drugmaker owned by a Chicago corrugated-cardboard maker called Stone Container. Then 35, he not only negotiated a job at the company but also an option to buy it should Stone exit the pharma business.

At LyphoMed, he demonstrated a talent for marketing straight out of Mad Men. One of the company’s major products was the formula used to tube-feed hospital patients. LyphoMed’s product contained vitamins and electrolytes, or micronutrients, and Kapoor seized on the term “micronutrients” as a hook to get his salespeople into otherwise uninterested hospitals. “I always believed in marketing,” Kapoor says. “You might have a great thing—but if you don’t know how to market, then you can’t succeed.”

In 1981, Kapoor pulled together a syndicate of investors to help him buy LyphoMed from Stone Container for $2.7 million (about $6.7 million today). Kapoor took LyphoMed public in 1983. Sales boomed as Congress passed laws favouring generic medications. From 1983 to 1989, LyphoMed’s sales increased from $19 million to $159 million.

When Kapoor tells this story, however, he leaves out a key part: His near-constant battles with the FDA. LyphoMed’s drugs were not produced in a sterile environment, the agency alleged: There was broken glass in what was supposed to be a sterile room. In 1987 and 1988 LyphoMed recalled hundreds of thousands of vials of various drugs, eventually entering a consent decree with the FDA to fix the problems. The FDA reported that the resulting shortage of vitamin B1 for tube-feeding resulted in three patient deaths. In 1990, a congressional sub-committee called LyphoMed’s manufacturing problems “legendary”.

Kapoor found a buyer, anyway: In 1990, Fujisawa Pharmaceutical, a Japanese drug giant, bought LyphoMed in a deal that valued the company at almost $1 billion. Kapoor personally pocketed $100 million after taxes.

In 1992, Fujisawa sued Kapoor for that entire $100 million, saying LyphoMed’s FDA problems were worse than it had been led to believe. He called the charges “preposterous” and settled for an undisclosed (but smaller) amount in 1999. “I don’t know how much you know about Japan, but to them, face-saving is very important,” he says. “Their way of face-saving was saying: ‘John did this’.”

The $100 million fortune allowed Kapoor to spread out his bets. He would found or take controlling stakes in multiple companies at once, and assume the chief executive role only when something went wrong. “In my career, my plan has always been: I am the last guy standing,” Kapoor says. “I’ve always taken the company to the finish line. If something happens, I just don’t run away and say, ‘Okay, I’m done’. I say, ‘Okay, I have a big stake in it, and I know the strategy’, and so on a temporary basis I step in and try to see what needs to be done.”

Consider Akorn, a Lake Forest, Illinois, generic-drug company that accounts for the biggest share of Kapoor’s net worth. Over the past ten years, Akorn’s shares are up by 728 percent, and Kapoor’s 26 percent stake in the company is worth $890 million. But it came close to being worth nothing.

Kapoor invested in Akorn in 1991, as the company grew through mergers with several other firms. In 1996, he became chief executive amid what he remembers as concerns about the company’s accounting. He stepped down two years later. He was back as CEO in 2001 as another set of accounting mistakes occurred. The FDA was also investigating problems at the company’s plant in Decatur, Illinois, which were eventually resolved. Kapoor stepped down again at the end of 2002.

In 2007, the FDA warned of more manufacturing problems, some of which had persisted since 2004. Debts piled up. In 2009, Akorn’s annual report said there was substantial doubt about its ability to continue as a going concern. The share price fell as low as 75 cents.

Akorn didn’t turn around until Kapoor brought in another new chief executive, Raj Rai, in 2009. Rai had previously run another Kapoor company, a pharmacy called Option Care, which was sold to Walgreens in 2007 for $850 million, including debt. Rai focussed Akorn on its core businesses, eye drugs and sterile injectable medicines for hospitals, jettisoning low-margin businesses, including vaccines. Akorn shares now trade at $27, a longtime disaster that turned into a huge win.

It was at a company called Sciele Pharma, originally called First Horizon, that the stage was set for Insys Therapeutics and its aggressive marketing of a powerful narcotic. Kapoor co-founded the company in 1992, linking up with an experienced drug marketer, Patrick Fourteau, who had previously run a contract sales force that pharma giants could quickly hire when they needed extra help. Sciele sold heart, paediatric and allergy drugs. Its biggest product was a blood-pressure pill.

Instead of hiring experienced pharmaceutical salespeople, Fourteau hired recent college graduates, nurses and other health care professionals, paying them low salaries but giving them big bonuses if they got doctors to prescribe Sciele’s drugs. Fourteau felt this was better for a small drugmaker. “The big pharma guys—especially in sales—that we recruited were the rejects of big pharma,” he says. “When they came to a small company, they thought they owned the world, and they were telling the management how to run the show.”

When they were just selling blood-pressure pills, this strategy worked admirably. In 2008, Sciele was bought by the Japanese drug giant Shionogi for $1.42 billion. By that time, Kapoor had already sold his shares and stepped down from the board.

At Sciele, he’d become fascinated by another of its products: A spray form of nitroglycerin used by heart patients to stop attacks of chest pain. “Patients loved it,” Kapoor says. “I started looking into the sprays, and to my surprise, I found it was the only product that was sold as a spray in this country.” What other drug would work well as a spray? Well, fentanyl, which cancer patients needed for rapid relief of pain. The idea wasn’t a fit for Sciele, so Kapoor brought it to Insys, a small company he’d founded in 2002. Fourteau joined the board in 2011, and Insys decided on a sales-force strategy much like Sciele’s, with young, aggressive salespeople. Asking them to sell a potentially deadly narcotic on an incentive plan created a powder keg primed to explode.

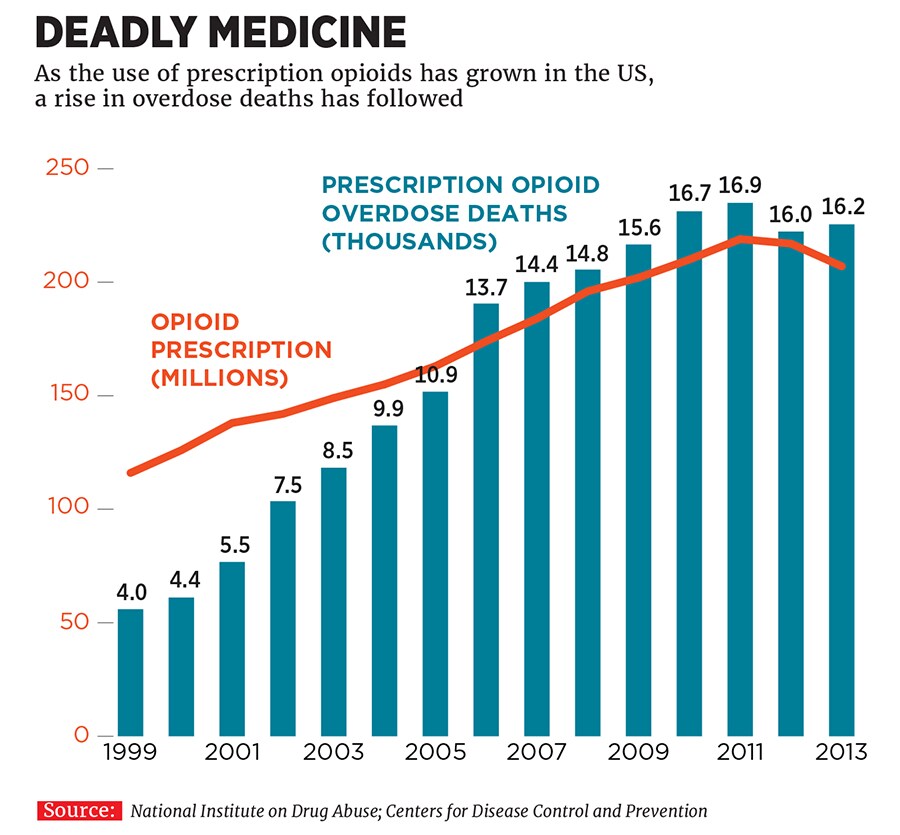

The market for prescription opioids is lucrative but fraught with ethical problems. A marketing push by Purdue Pharma in the 1990s resulted in its OxyContin becoming widely used—and abused. Since 1999, the number of prescriptions for opioid pills has quadrupled. The number of annual overdose deaths has quadrupled, too, to 19,000 per year.

Kapoor points out that his drug, Subsys, is but a drop in this flood. Superpotent forms of fentanyl meant for cancer patients are prescribed only 130,000 times a year, Insys says, compared to 200 million for opioids as a whole. (It’s difficult to say how many people use the drugs, since patients get multiple prescriptions.) These drugs relieve severe pain, but they come with their own legal problems. In 2008 Cephalon, a Frazer, Pennsylvania, drugmaker, paid $425 million and pleaded guilty to criminal charges involving drugs such as Actiq, a fentanyl lollipop. The Department of Justice (DOJ) alleged Cephalon had promoted Actiq, meant only for cancer patients, for a wide range of uses, including pain associated with migraines, sickle-cell anaemia and changing wound dressings. Worse, prosecutors said Cephalon pushed the high-dose narcotic to patients who had not previously developed a tolerance to opioids and might have died from their first exposure to such a potent dose of fentanyl. Despite the penalties, Cephalon more than survived: Teva Pharmaceuticals, based in Israel, bought it in 2011 for $6.8 billion.

To navigate this treacherous legal and ethical territory, Insys’s board, led by Kapoor, picked as chief executive a man in his mid-30s with little pharmaceutical experience named Michael Babich, whom Kapoor had originally recruited from Northern Trust, a wealth management firm, to work in his family office. Babich, in turn, chose Alec Burlakoff, who had marketed similar narcotics for Cephalon and had been mentioned in a case alleging off-label marketing, to head the sales force. Both have since left the company and did not return repeated calls for comment.

“I think what happened with Insys is that we grew very rapidly,” Kapoor says. “We have over 500 employees. I think a lot of things in a business, any business, especially when you have a fast-growing company, you’re in a very dynamic situation. Every day there is some decision that needs to be made. Mike did a good job. Yeah, we have some issues with DOJ. But I think, operationally, I felt that Mike may not be able to handle that with so many things happening.”

One way drug companies promote medicines is by paying doctors to give talks. This rewards doctors who like a company’s products and helps create new converts. In 2015, Insys paid doctors $6.3 million for activities that included speaking, according to data collected by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Four doctors received fees of over $100,000, and 11 more received at least $75,000.

Speaking fees aren’t illegal unless they are used as bribes for prescribing drugs for unapproved uses. That may have happened. Heather Alfonso, a nurse practitioner in Connecticut, pleaded guilty to charges of federal anti-kickback laws in June 2015. Prosecutors alleged that she had received speaking payments of $83,000 and prescribed $1.6 million worth of Subsys, largely to patients who did not have cancer. (She worked at a pain and headache centre.) She did not contest allegations by prosecutors that, in many cases, she was paid merely to go to dinner with a few people.

In February 2016, a former Insys sales representative, Natalie Reed Perhacs, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate anti-kickback statutes. Alabama prosecutors alleged she’d been hired because a doctor who prescribed Subsys “developed a certain affection” for her and that she arranged speaking fees for him and a colleague in return for their prescribing Subsys. Prosecutors claim she made more than $700,000 between April 2013 and May 2015, despite having a base salary of only $40,000 a year. Neither Alfonso nor Perhacs has been sentenced neither has commented for this story.

The allegations made by civil prosecutors in Oregon and Illinois mirror the picture created by the guilty pleas, documented with emails and text messages from Insys employees. The Illinois complaint alleges that Insys paid $84,400 to one doctor for 46 talks even though the company knew he had been indicted on federal false-claims charges. According to the complaint, an Insys sales rep emailed his supervisor and Babich, the CEO, saying that the doctor “runs a very shady pill mill and only accepts cash”. Later on, the same salesperson sent a message to a supervisor saying the doctor’s Illinois office was being watched by the Drug Enforcement Agency but that he was planning to start prescribing Subsys from another office in Indiana. The supervisor responded by saying the doctor would become the salesperson’s “go-to physician” and advising: “Stick with him.”

In another case, Oregon civil prosecutors allege, Insys hired the son of a physical medicine and rehabilitation doctor as a salesperson. (Their full names are redacted.) The son told his bosses—and later swore under oath—that his father did not treat any cancer patients. But the pressure from Insys to get him to prescribe Subsys wouldn’t stop. The company paid another physician $1,600 to have dinner with him to try to persuade him to write Subsys prescriptions. And they kept pressuring the son. “This company really wants to make you a speaker,” the son wrote to his father. “Apparently Kapoor had good things to say about you. The VP of sales wants to speak with you. I apologise for being pushy.”

The Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, a non-profit focussed on investigative reporting, obtained a recording in which Insys employees seemed to discuss getting insurers to pay for Subsys for patients who don’t have cancer.

Babich stepped down in November 2015, and Kapoor took over, as he has done so often when his companies get into trouble. His main defence, over three hours of interviews, is naiveté.

“I look at doctors and we think, professionally, they’re all ethical and all that,” Kapoor says. “I learnt that in certain areas, like in pain management or in opioids—this is public information, I’m not making it up—that there are doctors that overprescribe and things like that.” On speaker programmes: “We have very strict company policies,” Kapoor says. “If something happened in the field, sometimes the company may not know about it.”

It’s hard to believe that someone could run pharmaceutical companies for almost 40 years without realising some doctors overprescribe medicines, particularly pain medicines. Kapoor—and Insys shareholders—would like to move the focus past Subsys, hoping sales, which have dropped in the wake of bad press and government investigations, stabilise. He would like the focus to be on other drugs. Insys just received FDA approval for a synthetic version of THC, the compound in marijuana, to treat nausea. It is developing a spray version of naloxone, the life-saving antidote for opioid overdoses, and a synthetic version of cannabidiol, a component of marijuana that has shown promise in preventing seizures. Maybe after things with the Department of Justice are finally settled, that will be possible.

Maybe it will be possible after Kapoor steps down. Other small drugmakers have made big ethical missteps and moved on. But the problem with (allegedly) pushing a narcotic for unapproved uses is this: Even after you stop, the consequences are painful.