Meet Andrew Beal, the Warren Buffett of the banking business

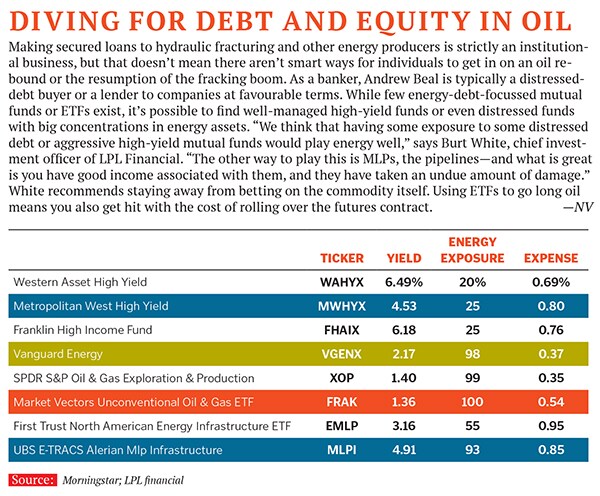

America's richest and most successful banker, Andrew Beal, is flush and ready to pounce on distressed oil and gas frackers

The past few years have been unsettling for Andrew Beal, the publicity-shy billionaire banker from Plano, Texas, who has a penchant for high-stakes poker. Like other smart money men, Beal is leery of asset prices fuelled by central bank intervention. So Beal hasn’t been making many loans recently and instead has built up a sizeable war chest of capital—enough to make more than $20 billion in fresh loans.

“There has not been anything to invest in. It’s the craziest environment, a world flooded with money,” says Beal. “It’s hard to sit by and pick your nose when you want to be doing deals.”

But with West Texas crude prices now down by 50 percent, to $50 a barrel, and many US oil and gas companies scrambling for cash, Beal has been quietly building an oil and gas lending team at his Texas bank, and though he has yet to close on his first deal, he expects to pull the trigger soon. “We are trying to get real active in the oil patch,” he says. “We’re looking at some decent-size deals, hiring people—we are going to go after it.” According to Beal, volatility will become the driving force in markets once the Fed actually begins raising rates. But this will have little effect on the inevitability of oil’s long-term price appreciation.

Andrew Beal, 62, is one commercial banker investors should pay attention to. With a self-made fortune estimated at $12 billion, he is the Warren Buffett of the banking business. Just as Buffett runs his insurance-centred holding firm, Berkshire Hathaway, almost as a personal hedge fund, so, too, does Beal run his bank. But unlike Buffett, Beal doesn’t have to entertain shareholders at annual meetings because he’s the sole owner of Beal Bank, which has 37 retail branches and $3.6 billion in deposits insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

A math whiz who left Michigan State at the age of 20 to earn millions rehabbing and flipping apartment buildings, Beal founded his bank in 1988. It grew fast and became very profitable until 2004, when Beal got nervous about lax underwriting and risky terms in the market for residential and commercial real estate. So he stopped making loans, shrank his assets and all but shut down his bank. Beal spent the next three years honing his backgammon game and learning to race Nascars. After the financial crisis hit, Beal went into action, deploying his capital and snapping up distressed commercial and real estate loans—many from failing or failed banks that had been reckless. He more than tripled his bank’s assets to $11 billion, making enormous profits.

Then Beal put the brakes on again. He became convinced that central bankers had helped fuel a new credit bubble. He didn’t go as far as he did before the credit crisis—when Beal Bank was laying off workers while the balance sheets of most other banks swelled. But in the last two years or so, Beal Bank has been experiencing a high level of loan payoffs as people and businesses refinance their loans. Beal Bank has been originating only about $1.5 billion in loans a year.

By the end of 2014, Beal Bank’s assets had shrunk to $7.9 billion, and his dry powder was mounting. Still, the bank was profitable, earning $547 million on $611 million of net revenue last year. Now Beal Bank has in excess of $3.3 billion in equity capital, and its leverage ratio is approaching an unheard-of 50 percent of assets. The FDIC defines a well-capitalised bank as one that has a ratio of 5 percent capital. JPMorgan Chase’s leverage ratio stands at about 5.9 percent.

Meanwhile, energy-producing companies, particularly those in the much-hyped hydraulic fracturing business, are busting loan covenants and are trying to preserve their loan facilities. Beal is already working on some potential deals. “You can make some decent loans today that are very well secured,” he says. “The only place for oil prices to go is up over the medium to long term. Short term, anything can happen, but oil is not going to go down over the next seven years.” Beal is not the only big investor on the hunt for bargains in the oil patch, there are others too. Hedge funds like Clint Carlson’s Carlson Capital and billionaire Marc Lasry’s Avenue Capital have been raising new vehicles to target the debt and equity of energy companies. Likewise, the biggest private equity firms have recently raised some $20 billion for energy sector investments and are rushing to do deals. The Blackstone Group, for example, just finished raising a $4.5 billion energy fund in February and is reportedly raising another $1 billion to buy bonds and distressed loans of oil and gas companies. Blackstone’s credit division recently committed $500 million to fund drilling programmes for Linn Energy and got an 85 percent working interest in some of Linn Energy’s oil and gas wells in return. The Carlyle Group has about $9 billion marked for energy deals, and its co-chief, billionaire David Rubenstein, recently said, “There is no other sector in the world that we are as bullish on as we are on energy.”

These savvy financiers are mostly targeting oil and gas debt rather than equity. Already under regulatory pressure, many regional banks situated in drilling areas like Texas are retreating from the oil and gas sector, unloading their loans. Just last year, some $230 billion of loans were extended to US oil and gas drillers, according to Dealogic, but now some banks, facing losses, are heading for exits. “When oil was $130 a barrel, they were all lending like crazy. Now it’s $50, and they don’t want to make a loan,” says Beal.

Banker Beal is interested only in extending secured loans to energy producers—those backed by producing reserves and cash flow. “The only lending we will do is the first lien secured facility, and the good news is that appears to be where the opportunity is these days,” says Beal. By contrast, hedge funds and private equity players are interested in tranches of debt that are typically subordinated but that can convert into equity or control positions.

It would be difficult to find an investor who has played the peaks and valleys of the last decade’s credit cycle as skillfully as Beal—even though he is completely removed from the stock market. Beal thinks people who dive into stocks today should be wary. “I am not predicting a crash, but there will be a lot of disappointed investors,” he says.

Don’t confuse Beal’s cautionary tone for an aversion to risk. Beal is a well-known whale at the poker tables in Las Vegas, where his bank happens to have a second headquarters. Winning or losing $5 million or $10 million in a game of Texas Hold ’Em is not unheard of for the brash billionaire, and right now he’s prepared to go all-in with his primary asset, Beal Bank, on America’s energy sector.

“In my lifetime there have been game changers, but in ten years to have gone from the peak-oil mind-set to where we now essentially have a 100-year supply of free energy—natural gas from $3 to $5—is just unbelievable,” he says, noting technological wonders like fracking, which now have the US producing nine million barrels of oil per day. “How do you take a country like the United States, give us 100 years of free energy and not be optimistic?”

First Published: May 14, 2015, 06:42

Subscribe Now