Axel Dumas, sixth-generation scion of the Hermès luxury goods dynasty and since February its CEO, has a secret. Sitting in his tenth-floor office with a glittering view of Montmartre, for an appointment that’s taken weeks of negotiations, Dumas is four days away from replacing Christophe Lemaire, the highly regarded designer of Hermès’ important ready-to-wear women’s fashion line.

So what does the 44-year-old chief executive want to talk about? “The main strength of Hermès is the love of craftsmanship” is the first thing he says in his accented but fluent English. Ten seconds later: “We see ourselves as creative craftsmen.” Thirty minutes in: “The philosophy of Hermès is to keep craftsmanship alive.” After two hours, Dumas is still holding back on the granular details, no matter which way I ask, of how Hermès has emerged as the most ascendant company in the $300 billion luxury market. No guidance on the art of selling everything from $94,000 crocodile leather T-shirts to $1,275 beach towels.

And certainly nary a hint that Dumas would imminently replace Lemaire with Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, the 36-year-old design director at The Row (the couture clothing brand run by the Olsen twins), even though he knew that I would soon find out along with the rest of the world.

But all this obfuscation and secrecy, perversely, also drives home what has prompted Hermès’ stock to shoot up 175 percent over the past five years. Indeed, on Forbes’ accompanying list of the world’s most innovative public companies, the 177-year-old Hermès is ranked No. 13, ahead of companies such as Netflix, Priceline and Starbucks. The list, determined by measuring which companies trade at a level incongruous to their underlying financials and assets, measures each company’s market-tested premium for innovation. Dumas’ high-flying stock, accelerated by LVMH’s apparent interest in a takeover several years ago and a thin float, doesn’t rely on the technological efficiencies that drive so many others on this ranking. Nor is it propelled solely by his endlessly repeated “craftsmanship”, though that’s certainly an essential underpinning.

At Hermès, any lasting premium derives from mystique. After all, selling a commodity ultimately boils down to one thing: Price. But selling beautiful objects that people don’t inherently need? That requires a more complicated formula that Hermès has mastered: Last year, the company set a record, reporting an operating profit of $1.69 billion with $5 billion in sales—the fastest-growing company in its industry over the past six years, fuelled by a sort of branding and marketing craftsmanship as exacting as the stitching on one of its iconic Birkin bags.

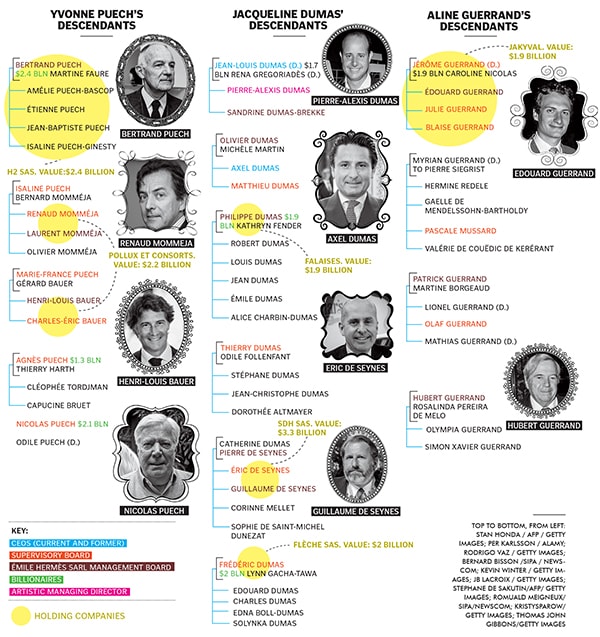

The payoff for this softer kind of innovation is enough to make a social media startup founder blush. In examining Hermès’ ownership structure, Forbes estimates that at least five family members now belong on our global billionaires list. And the collective fortune for Dumas’ family now tops $25 billion—more than the Rockefellers, the Mellons and the Fords. Combined.

The creation of one of the world’s great wealth machines, built within the kind of sprawling family structure that tends to stifle innovation rather than spawn it, boils down to three dates.

The first one traces back to 1837, when a leather-harness maker named Thierry Hermès established a shop in Paris. To the beau monde who relied on equipage for travel, the quality and beauty of Hermès bridles and harnesses were unrivalled. Thierry had only one child, Charles-Émile, who moved the business to 24 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where it remains to this day. Charles-Émile, in turn, had two sons, Adolphe and Émile-Maurice, who transformed the business into Hermès Frères. But eventually Adolphe believed the company had a limited future in the era of the horseless carriage, leaving Émile to carry on. Émile had four daughters (one of whom died in 1920), which explains why no one involved in the family business is named Hermès. It’s those descendants—the fifth and sixth generations—who control the company today.

![mg_77543_dumas_family_280x210.jpg mg_77543_dumas_family_280x210.jpg]()

The second turning point for Hermès came far more recently, in 1989. Over the course of the 20th century, Hermès remained one of the world’s great luxury brands. But with its focus on artisans—every one of its leather goods is made by hand in 12 workshops in France by more than 3,000 skilled workers—it was built to trot, not gallop. Under Axel Dumas’ uncle, Jean-Louis Dumas, CEO from 1978 to 2006, much of the family ownership had split into a Russian- nesting-doll-like group of six holding companies. Layered atop that was an ingenious two-tier management structure engineered by Jean-Louis. One was more about ownership—a family-only entity named Émile Hermès SARL, after their ancestor—that sets budgets, approves loans and exercises veto power. The other, Hermès International, oversees the day-to-day management of the company and incorporates outsiders (non-family members currently occupy 4 of 11 board spots).

As with everything Hermès, it was byzantine and painstakingly mapped out. It worked. The new structure helped Hermès in 1993 sell 4 percent of its shares to the public, giving younger generations a way to liquidate while allowing the family to keep control. And that new war chest helped encourage Hermès to think bigger than a fine leather goods maker. Jean-Louis Dumas expanded the company into men’s ready-to-wear attire, tableware and furniture. Between 1989 and 2006, sales grew four-fold, to $1.9 billion. Still, it wasn’t a foolproof plan.

Bernard Arnault, head of the world’s largest luxury company, LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton), took note of the growth. Hermès fit right into his burgeoning portfolio in the same way Dior and Fendi did. So, in 2002, Arnault began accumulating shares, using the same cash-settled equity-swaps strategy that hedge funds use to amass positions without technically needing to disclose. In 2010, Arnault publicly revealed that he controlled 17 percent of Hermès and a takeover seemed a fait accompli. With the stock up 30 percent on such speculation, the three branches of the remaining Hermès family were expected to take the money and run.

Arnault’s move, instead, created the company’s final turning point. Rather than cash out, the family circled its leather-upholstered wagons. Patrick Thomas, the non-family-member who served as CEO between Jean-Louis Dumas and Axel Dumas, famously declared that “if you want to seduce a beautiful woman, you don’t start raping her from behind”.

In another bold move, in 2011 more than 50 descendants of Thierry Hermès pooled their shares into what was essentially a $16 billion co-op called H51. The contributors— representing 50.2 percent of all company shares—contractually agreed not to sell any shares for the next two decades. Two other major shareholders, fifth-generation family members Bertrand Puech, now 78, and Nicolas Puech, 71, kept their shares outside H51 but also held the line against LVMH, agreeing to give other family members the right of first refusal if they ever decided to sell.

Staring at a chart of the family’s baroque ownership structure can cause dizziness. LVMH and Hermès continue to fight it out in court, with Hermès even pursuing criminal charges for insider trading LVMH has countersued, claiming false accusation. (“The battle of my generation,” says Axel Dumas. “Hermès is not for sale, and we are going to fight to stay independent.”) However, it turns out the family’s unified front has proved profitable for Hermès. For the company, the two-decade time frame once again allows it to make long-term decisions as if it were a private company. And for the family, it was a burn-the-ships decision. The lockup means that most family members must make do with dividends, although for people like Nicolas Puech, whose $2.1 billion holding generates an annual dividend of around $20 million, it’s enough to keep him in horses at his Spanish estate. Thierry Hermès would surely have approved.

Mystique is hard enough to achieve, let alone maintain over two centuries, but here’s one example of how Hermès carefully cultivates its image: In May of this year the world’s most elegant carnival was staged inside an august space on Wall Street: Financier JP Morgan’s legendary corner bunker at 23 Wall. A photo booth was set up to capture celebrity guests atop carousel horses, a faux synchronised swimming dance number was performed, and a fortune-teller predicted the future based on a selection of silk scarves.

This is how Hermès celebrated its first women’s runway show in the US. Much as one might want to congratulate the marketing department for the sensory overload spectacle—down to taste (champagne was served from a “bangle bar” shaped like an enamel Hermès bracelet) and smell (white-gowned ingenues proffered flowers scented with the brand’s latest fragrance, cooing, “Would you like to smell Jour d’Hermès Absolu?”)—that would be impossible: Hermès doesn’t have a marketing department.

Why should it? McKinsey doesn’t have a consulting department nor does Microsoft have a software department. Marketing is Hermès’ core business.

At the carnival, standing atop the red carpet and greeting the 800 VIPs, including Anna Wintour, Jodie Foster and Martha Stewart, as they entered, was Hermès’ de facto head of marketing: Axel Dumas. “Our business is about creating desire,” he says. “It can be fickle because desire is fickle, but we try to have creativity to suspend the momentum.”

To instil this ethos in the company, all new employees are steeped in Hermès’ desire-creating culture through three-day sessions called “Inside the Orange Box” (so named for the signature packaging) that trace the company back to Thierry Hermès and give a history of each of the product categories (or “métiers”, in Hermès-speak, which is French for a trade). Thus, every Hermès employee can wax philosophical about the Kelly bag, the trapezoidal saddle bag from the 1890s that Axel Dumas’ grandfather transformed into a women’s handbag and that Grace Kelly made iconic.

But the main guardian of the Hermès mystique is the family itself. According to a former top Hermès executive, a luxury consultant with close ties to Hermès, as well as one of the company’s Asian executives, non-family executives rarely make strategy or branding decisions without the input of at least one Hermès descendant, many of whom may wear several hats at the company and thus hold sway over multiple métiers.

“If there are three or five people around the table and the family member says ‘yes’, who will say ‘no’?” says the consultant. “Nobody is powerful enough to counter that.”

Once product and marketing sensibilities are vetted, however, a top-heavy roster of lieutenants is given a large degree of autonomy to execute. Creative director Pierre-Alexis Dumas (Axel Dumas’ first cousin) sets the tone, but the company perfumer (or “nose”), Jean-Claude Ellena, runs a laboratory inside his home outside the city of Grasse and develops Hermès’ fragrances. Another cousin, Pascale Mussard, heads Petit h, a division that makes one-of-a-kind objets from Hermès remnants, scraps of crocodile skin or swaths of unused silk. And the events teams, once given their marching orders, let their whimsy show, as evidenced at JP Morgan’s old office. “We’ve always said we don’t take ourselves too seriously at Hermès,” says the company’s US CEO, Robert Chavez.

The autonomy is even greater at the retail level. Twice a year, more than 1,000 store representatives come to Paris for an event called “Podium”, where they select which pieces of merchandise they will carry. The family has decreed that each flagship store must pick at least one item from each of the 11 métiers—thus pushing them beyond handbags, scarves and ties to perfume, jewellery, watches, home accessories. In giving these managers an elaborate menu to choose from, each store boasts merchandise unique to itself. The moneyed globetrotters who constitute the Hermès customer base constantly find themselves on a worldwide treasure hunt. For example, only in Beverly Hills can they find a $12,900 basket- ball, and the $112,000 orange leather bookcase was sold exclusively at the Costa Mesa store. So when they fall in love with that $11,300 bicycle there’s a pressure to get it, since the company’s website, while ahead of many luxury competitors, offers just a smattering of the Hermès product line.

The top case study at the “Inside the Orange Box” indoctrination, according to those who have attended, surrounds the Hermès Birkin bag. And rightly so. The Birkin, a chic cousin to the Kelly bag that runs from $8,300 to $150,000, embodies everything that keeps the Hermès brand so profitable.

It also represents the highest order of Dumas’ fabled craftsmanship. When I visit the six-story workshop in a Parisian suburb, I watched French leatherworkers, who must have at least three years of training before ascending to Birkin duty, hand-stitch each crocodile and goat-skin leather seam with two needles and beeswax-covered thread, and hammer the tiny rivets that attach the clasps to the leather. Vertically integrated leather, no less: In another example that defines a different kind of innovation, Hermès purchased two crocodile farms in Australia in 2010 and an alligator farm in Louisiana to supply the finest skins.

![mg_77545_luxury_goods_280x210.jpg mg_77545_luxury_goods_280x210.jpg]()

But since taste is fickle, the ability to keep the Birkin as apparel’s ultimate status symbol proves to be a cold, hard business. The genesis story helps: As with the Kelly bag, it began with a fashion symbol. In 1981 Jane Birkin, a British actress and “It Girl” from London’s Swinging ’60s, was sitting next to Jean-Louis Dumas on a flight between Paris and London when he noticed her overstuffed straw bag. “You should have one with pockets,” he told her. “The day Hermès makes one with pockets, I will have that.” “But I am Hermès,” he told her and soon ordered up a variation on the Kelly with a similar belt and lock closure. The Birkin debuted three years later and became an instant hit.

While Hermès officially denies that bold-faced names get special treatment in procuring one (“We consider all of our clients to be celebrities in their own right,” says Chavez), the Birkin bag somehow, over the decades, finds its way onto the arms of the most current set of tastemakers. Beyoncé, Lady Gaga and Kim Kardashian all sport one. Victoria Beckham is said to have a collection of Birkins worth over $2 million. At LVMH, paid celebrity endorsement is an art, from Michelle Williams representing Louis Vuitton bags to Charlize Theron as the face of Dior perfume at Hermès, the perception (and reality) that the A-list is truly its customer proves to be a less expensive, more authentic endorsement.

The velvet rope beckons the rest of us. You won’t find a Birkin or Kelly bag online or even in a store. And Hermès says it has done away with its reputed waiting list. “They would probably be seven to 10 years,” says Chavez. “If you want a bag in lizard or crocodile it could take longer.”

Like the most exclusive clubs, membership qualifications are intentionally vague. “There is no specific rule about it,” says Dumas. Echoes Chavez: “There’s really no system.” When I went to the New York City flagship on Madison Avenue to ask about buying a Birkin, I was told there were none in the store.

“When will you get one in?” I asked innocently. “I couldn’t say.”

“Could you take my information and let me know when one comes in?”

“We don’t do that here.”

“I’ve heard there is a waiting list.” “We don’t do that here.”

“When was the last time you had a Birkin for sale in the store?” “I couldn’t say.”

“I’ve heard that if I’m a good customer and spend a lot of money, I have a better chance of getting a Birkin.”

“We don’t do that here.”

Short of mega-influence, the only sure way to get one of the bags is to buy it on the auction market. The appreciation of Hermès bags can be staggering, particularly for the more exotic skins. In 2013, Heritage Auctions sold a collection of Birkins for three to five times the pre-sale estimates. The record for a Birkin was the $203,150 that a collector paid in 2011 for a red crocodile bag with white-gold-and-diamond detailing. That’s mystique at its poshest level.

Axel Dumas even orders lunch in a Hermès way. “I’ll have your best steak,” he says, paying little mind to the menu, while dining at New York’s Capital Grille.

He’s talking about what’s next for the company. Hermès, with 318 stores on five continents, is opening a new flagship in Shanghai (it already has three other maisons there). While Dumas is renovating stores in Indonesia, Taiwan and London, next year will carry an American focus, with seven expansions and openings, including a Manhattan perfume store and a new location in Miami.

Though Dumas is typically circumspect about many initiatives, he guarantees one thing: That Hermès, for all its legal battles, will not succumb to LVMH. “The mood of the family has always been very strong and very determined,” he says. “We are here for the long term.” Could he imagine his son or daughter following in his footsteps? He says he won’t try to persuade them. But he also makes it clear that some member of the seventh generation would be expected to step up and continue the tradition of product excellence and sales sorcery. “I am just the tenant for the next generation.”

Additional reporting by Hannah Elliott and Arooba Khan