LinkedIn Is Raking in the Moolah

Facebook gets all the attention, but LinkedIn has figured out how to turn a social network into a cash machine. And it doesn't even need you to be there to make money

LinkedIn’s Chief Executive, Jeff Weiner, doesn’t want to talk about Facebook. No, no, no. “I’m not going to get into comparisons with them,” he declares. And yet a few minutes later Weiner rises from his chair, walks over to a whiteboard and energetically sketches a diagram that the world’s other giant social network can’t match.

Weiner draws three concentric circles to show how LinkedIn makes its money. The outer one is marketing and advertising. Next, subscriptions. And in the centre is LinkedIn’s richest and fastest-growing opportunity: Turning the company’s 161 million member profiles into the 21st-century version of a “little black book” that no corporate recruiter can live without.

“That’s the bull’s-eye,” he says. Recent attention in the social space has focused almost entirely on Facebook, with its 900 million users, 28-year-old celebrity CEO and bumpy initial public offering. In the first month after its May 18 IPO, Facebook stock skidded an embarrassing 17 percent. Hardly anyone noticed, meanwhile, that LinkedIn shares have leaped 64 percent this year. Mark May from Barclays Capital says LinkedIn is on track to gross $895 million and net $70 million, up 71 percent and 100 percent, respectively, from 2011.

Compare this to even three-and-a-half years ago, when Weiner joined LinkedIn. The company was running a $4.5 million annual loss, paying bills mostly by hawking online ads and peddling “premium subscriptions” for as little as $9.95 a month. LinkedIn was too bashful for its own good.

That’s when Weiner’s bull’s-eye emerged. Rather than try to wring 20 bucks here and there from individual users, he refocused the company on selling a vastly more powerful service to corporate talent scouts, priced per user at as much as $8,200 a year. Today thousands of companies use LinkedIn’s flagship Recruiter product to hunt for skilled achievers. In human resources departments having your own Recruiter account is like being a bond trader with a Bloomberg terminal— it’s the expensive, must-have tool that denotes you’re a player.

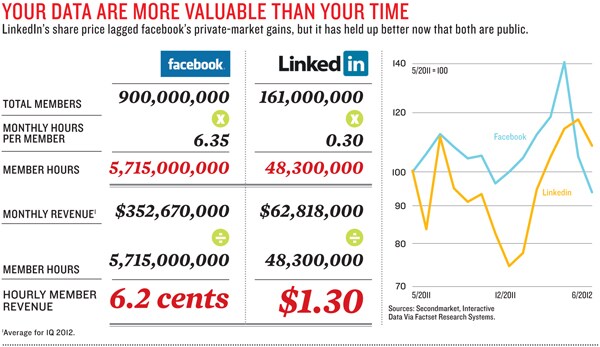

There’s no better way to understand LinkedIn’s quiet savvy, in the midst of Facebook’s noisy clatter, than to compare the two sites’ financial efficiency. Compare the revenue the rivals collect for every hour that each user spends on either site. LinkedIn’s tally: $1.30. Facebook’s: a measly 6.2 cents.

One could argue that it’s better to have a small slice of something massive than a big slice of something smaller. But the numbers above are further skewed by a simple fact: Facebook, which derives 85 percent of its revenue from advertising, makes money only when you’re on Facebook. Once you sign up for LinkedIn, the social network monetises your information, not your time. Mark Zuckerberg can crow about how his users spend, on average, 6.35 hours per month on Facebook versus 18 minutes for LinkedIn. But Facebook users may click on only one of every 2,000 ads. Ask yourself which model seems more sustainable.

These dynamics will get further magnified as the Web goes mobile. It’s hard to deliver ads to tablets and smartphones. At LinkedIn, where 22 percent of visits now come from mobile devices—versus 8 percent a year ago—this surge just means more of the kind of interactions and data that it can monetise.

To see how that plays out, wander the halls of a conference with Lars Schmidt, head of talent acquisition for NPR. “Recruiters don’t stay in the office anymore,” the public-radio executive explained one morning. “You need to be much more externally focused.” His old-fashioned ritual of swapping business cards has been redefined. Schmidt became a huge fan of CardMunch, a two-year-old iPhone app that turns photos of business cards into digital contacts. In January 2011 LinkedIn bought CardMunch and rebuilt it to pull up existing LinkedIn profiles from each card and prompt people to connect. The LinkedIn experience, in some ways, gets richer away from the desktop. Says Deep Nishar, LinkedIn’s senior vice president for products and user experience: “We love mobile.”

Much as LinkedIn’s long-term model makes sense, its near-term success stems from a manic dedication to selling services to people who buy talent for a living. During Weiner’s tenure LinkedIn has developed an intense, sales-focused culture in which new-account wins are celebrated by name at biweekly all-hands meetings. The best frontline salespeople for hot products such as Recruiter can earn $400,000 a year. And unlike at other Silicon Valley companies, where engineers rank as alpha dogs, LinkedIn’s salespeople pull off the most daring stunts. Sales-effectiveness leader Nate Bride once dyed his hair blue to match the LinkedIn logo—and shaved small parts of his skull to spell out the company name.

LinkedIn has doubled the number of sales employees in the past year, with the company now spending 33 percent of revenue on sales and marketing. That’s a startling number for a social network, more akin to the relentlessly hawking enterprise-software crowd. Oracle and Microsoft spend 20 percent of revenue on sales. Facebook spends 15 percent Google is at 12 percent. But Weiner makes no apologies. Each time the company has expanded its sales team for Recruiter and other hiring-solu- tions products, he says, the payoff has been “off the charts.” Sales keep surging, and existing customers keep spreading their enthusiasm for what LinkedIn has to offer. And once these sales are made, the customer becomes low maintenance and recurring. People familiar with selling Recruiter say LinkedIn keeps 95 percent of its big-company accounts each year. For smaller accounts the number is more like 80 percent. “I’m happy to invest,” Weiner says. “My concern was how quickly we could hire and still maintain quality.”

LinkedIn’s disruptive impact on the $27 billion recruiting industry can be seen in the stock prices of the job-hunting sector’s old guard. Heidrick & Struggles, a search firm that courts candidates the old-fashioned way, has slumped 67 percent in the past five years, compared with a 13 percent drop in the S&P Index. Monster Worldwide, which operates online job boards, has fared even worse, tumbling 81 percent. (Its shares briefly rallied in March on momentary speculation that it would be purchased—by LinkedIn.)

At the apex of the job market—CEO searches and the like—it’s hard to imagine the face-to-face niceties of traditional search giving way to LinkedIn’s more automated approach. At the other end of the spectrum, job boards provide faster results for low-paying, low-skill jobs such as cashiers and truck drivers. But LinkedIn enjoys a vast sweet spot between those two extremes, helping fill high-skill jobs that pay anywhere from $50,000 to $250,000 or more a year.

In a downtown office tower in San Jose, California, Jeff Vijungco bears witness to the reasons that big companies crave LinkedIn’s data. He is vice president for global talent acquisition at Adobe Systems, which employs 10,000 people and at any moment is likely to face at least 750 openings worldwide.

Traditionally, staffing agencies handled about 20 percent of Adobe’s hunts for highly specialised engineers and digital wizards. Vijungco chafed at that approach. Agencies were expensive, charging as much as $20,000 for each job filled. Retention rates on their placements could be disappointing. Still, there wasn’t an obvious alternative. Good people at other tech companies didn’t answer job ads such candidates wouldn’t switch employers unless someone found them and put forth an amazing offer.

Then a few years ago Vijungco staged a talent-scouting race. One pair of recruiters used the traditional way of finding 50 solid candidates for a technical job. Another pair used LinkedIn. “The ones using LinkedIn were done within hours,” Vijungco recalls with a grin. “The other ones were still going at it, weeks later.”

Today Adobe leases 70 Recruiter seats. A typical user is Trisha Colton, who leads Adobe’s hunt for digital media executives. On a recent afternoon she needed to fill five positions. With a few clicks of the mouse on her ThinkPad laptop, she could tailor a project-manager search that enabled her to look at possible candidates from 21 leading ad agencies, 15 publishing outfits and a host of other suitable backgrounds.

A few more tweaks of the dial and Colton had specified what current jobs these people should be holding, how many years of experience they should have and their locations. Moments later she had a list of 148 prospects. Recruiter informed her which candidates already knew peo- ple at Adobe, at least slightly. Colton could use that information to help open a dialogue. If no ties existed, she could use LinkedIn’s modified e-mail system to approach each candidate. “We’re saving millions of dollars this way,” Vijungco says. Search agencies now get less than 2 percent of Adobe’s business in the Americas.

Some small-business users have abandoned Recruiter, preferring to get by with cheaper, more limited access to LinkedIn’s data. But power users say LinkedIn is invaluable in finding hidden candidates who wouldn’t show up via traditional searches. One such devotee is Elisa Bannon-Jones, the hiring chief for Wireless Vision, a Bloomfield Hills, Michigan mobile-phone retailer.

Earlier this year Bannon-Jones was asked to find an accounting manager with entrepreneurial spirit. Regular job ads in the Detroit metro area flopped all she got were 100 unsuitable candidates. So she crafted a multistate search via LinkedIn. Her target: Accountants who had worked in similar retail companies and whose profiles also included magic words such as “launched,” “created” and “built.” Within days she had found an Avis veteran in Virginia who had developed billing systems all by himself. They chatted. She liked his initiative he liked the job, and Wireless Vision had its catch.

LinkedIn’s success is ultimately rooted in timing. Not the technology, which is a given, but rather the changing workplace ethos. When executives like the 42-year-old Weiner were growing up, the theory was that companies provided a career for life. Creating a public profile that could win recruiters’ attention would have seemed rude and risky.

Then came a barrage of layoffs, mergers and strategic zigzags that sent entire corporate divisions to the scrap heap. So employees at all skill levels returned the favour. They stopped feeling much loyalty to their employer of the moment. Filling out a LinkedIn profile started seeming downright wise.

Among the earliest people to grasp the importance of this social transfor mation was Reid Hoffman, a Stanford graduate who in 2000 became one of PayPal’s earliest executives. Hoffman needed a new project after PayPal was sold to eBay and cofounded LinkedIn in 2003 on the notion that getting lots of professionals connected in an online network was bound to be helpful, somehow. “We learned [from PayPal] that you could revolutionise an industry with people who are very smart, working hard and deploying a technology never seen before,” Hoffman told Forbes in April.

Hoffman’s vision took shape fitfully. By 2004 LinkedIn had 1 million members, with word of mouth pulling more people into the free site each week. Members posted their career bios.

They competed to build out contact lists that consisted of dozens or even thousands of current and former busi- ness associates. People who signed up for free memberships could prowl through one another’s contacts a little bit people who bought premium memberships could explore a bit more. It wasn’t clear, though, what else people were supposed to do.

As LinkedIn’s membership rocketed past 20 million in 2008, a winning business model began to take shape. Now LinkedIn’s database was rich not just with Silicon Valley programmers and venture capitalists but also with Wall Street traders, Texas geologists and highly skilled professionals of all callings outside the US Talent hunters were ready to pay big-time for a chance to connect with the entire LinkedIn community.

One of the first people who tried to sell the newly coined Recruiter service to big companies was Nathan Egan, a Villanova graduate now running PeopleLinx, a social business solutions company. While at LinkedIn he took on the greater Philadelphia territory in late 2008. Egan started selling Re- cruiter at $5,000 a seat, worried that customers would balk at the price.

“But banks didn’t mind,” Egan recalls. “Consulting firms didn’t mind at all.” Within a month LinkedIn had handed Egan a revised price sheet. Now the minimum order was three seats, at a total cost of $21,000.

Simultaneously LinkedIn was making a leadership change. The company’s founding CEO, Hoffman, was more of a venture capitalist by temperament. So by early 2007 Hoffman had recruited a veteran outside manager, Dan Nye, to try running the firm. But LinkedIn was having trouble meeting its financial targets and seemed to be spreading its energy too haphazardly among many projects that were behind schedule or having little impact. In December 2008 Hoffman hired Yahoo veteran Weiner to be president for a few months before taking over the CEO’s job.

Weiner’s fascination with Internet businesses dated back to 1992, when he was a senior at the University of Pennsylvania trying to make a desktop teleconferencing company work as part of an entrepreneurship class. A couple of years later he wiggled his way into the strategic planning department of Warner Bros, where he caught people’s attention, at age 24, with a detailed report arguing for Warner to take a bold digital strategy. “I was just this little pisher, a nobody,” Weiner recalls. “But they liked the report.”

He joined Yahoo in 2001 as a protégé of then-CEO Terry Semel, an ex-Warner executive. Starting in corporate development, Weiner ended up running Yahoo’s best-known properties, including mail, search, sports and news. Colleagues remember him as a tireless champion of data-driven decisions.

“Jeff has very strong applied-math capabilities,” says Andrew Braccia, an Accel Partners venture capitalist who worked with Weiner at Yahoo. “He wants everything measured.”

At LinkedIn Weiner showed a more nuanced touch. He spent his first few weeks on a listening tour, meeting with just about all of LinkedIn’s 338 employees either one-on-one or in small groups. Rather than repeat Yahoo’s mistakes of moving in too many directions, Weiner built his LinkedIn strategy around getting the simple stuff right. Fix the site so it doesn’t break down as often. Run a lot of tests to see what users want. Be rigorous about analysing data. Get the product right.

And then sell, sell, sell.

Weiner crystallised Hoffman’s original idea into a seven-word maxim: “connecting talent and opportunity at a massive scale.” That slogan carried LinkedIn toward a successful IPO in May 2011. Today Hoffman remains LinkedIn’s executive chairman and its largest shareholder, with an 18 percent stake worth nearly $1.8 billion, but spends most of his time at Greylock Partners, where he’s become one of Silicon Valley’s most active venture capitalists.

Weiner, who controls $300 million in stock even after selling 18 percent of his holdings, is now tasked with wringing ever more from the hiring market. This spring LinkedIn launched Talent Pipeline, a service for recruiters that allows tracking of interesting candidates who might not be ready to job-hop yet. Another initiative, being led by LinkedIn data scientist Peter Skomoroch, aims to find ways of analyzing members’ profiles in more detail. The goal: Distinguishing different levels of expertise between two candidates who may both claim expertise in an area such as protein folding or mobile apps.

Because the payoff for running a growing community is so obvious, LinkedIn spends briskly on new ways to get its free members to come back. Last year it launched LinkedIn Today, a customised news site that lets people see a front page tailored for their careers. LinkedIn also continues to expand its thousands of profession-specific discussion boards, which cater to everyone from auditors to zookeepers. Even if nobody did anything to improve Recruiter for the next five years, “the product would keep getting better every day,” asserts David Hahn, the company’s vice president for product management. “We keep adding members, expanding into new geographies, and our existing mem- bers keep adding more information. It’s important to recognize how valuable those trends will be for us.”

LinkedIn’s success so far makes it a target for younger startups. BranchOut is building a career-related social network based on members’ Facebook profiles. Identified.com awards high scores to its members with especially popular profiles. For some newcomers, though, it’s hard to develop big enough networks to be useful. BranchOut blasted invitations across the Facebook network, only to annoy some users, who shunned the new service for being “spammy.”

Not that LinkedIn doesn’t have problems. Running a social network that adds two new users per second makes it a target for mischief.

Last month a Russian hacker group breached LinkedIn’s company security system, gaining access to 6.5 million user passwords.While it doesn’t appear that member accounts were accessed, the attack displayed LinkedIn’s tardiness in implementing the most advanced password-encryption systems. “Ultimately you don’t want to be reacting to this kind of thing,” concedes Weiner, who says the company immediately stepped up in this area. “You want to make it so difficult to be hacked that break-ins don’t occur.” Any overseas unpleasantness, however, is outweighed by opportunity. Currently 60 percent of LinkedIn’s members are outside the US, but foreign revenue is only 36 percent. Evening that out would spell a large profit spike, so LinkedIn in the past year has opened sales offices in Germany, Japan, Brazil, India, Spain and Hong Kong.

Weiner has even grander plans. Specifically, he wants to use LinkedIn to create an “economic graph” that would show all the matches—and mismatches—between needed skills and available talent worldwide.

“This may be five to ten years away,” Weiner says. “But there could be data on every economic opportunity, every skill required to get those jobs and every company offering those roles. There could be a professional profile for every member of the 3.3 billion people in the global workforce. If that economic graph existed, imagine all the friction coming out of the system as those connections are forged.” That’s a vision as grand as Zuckerberg’s idea of every person on Earth hosting his personal life through a Facebook page— and given the trillions spent on business each year, it’s a bull’s-eye that’s potentially even bigger.

First Published: Jul 25, 2012, 06:04

Subscribe Now