Iflix: The Netflix for emerging markets

The race is on to sign up viewers for video-on-demand. Web veteran Patrick Grove says his Kuala Lumpur startup Iflix will be the winner in Asia and elsewhere

“We can revolutionise how movies and TV are consumed,” say Iflix CEO Mark Britt (left) and founder Patrick Grove

“We can revolutionise how movies and TV are consumed,” say Iflix CEO Mark Britt (left) and founder Patrick Grove

Image: Charles Pertwee for Forbes

Patrick Grove is leaning against the pool table in Catcha Group’s headquarters in the Mid Valley mall-lands of Kuala Lumpur. The internet pioneer has started company after company, but today he’s doing something different—he’s plugging a local tailor shop. “I’ve worn a suit twice in the past five years,” he jokes. “To get married… and divorced.”

He was getting an award at a gala dinner that night, but he had left his only suit at his second home in Singapore. A call to the tailor produced an offer: Tape a promotional video for the shop and a bespoke suit would be his for free. So here he was, being asked by a cameraman to describe himself. “I’m proudly from Southeast Asia,” Grove says. “I split my life into two halves: Before 24 years old and everything after—when I became an entrepreneur.” And his life goal? “I want to create a great company that goes global and disrupts an entire industry.”

The company is two-year-old Iflix. The industry is subscription video-on-demand. Grove is targeting developing countries, and Iflix, part of his Catcha Group, is now operating in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and elsewhere. Iflix offers unlimited viewing of 20,000 hours’ worth of movies and television shows, available any time of day, for a monthly fee roughly equal to the price of a pirated DVD. That’s usually between $2 and $3, depending on the country. The content comes from more than 100 studios and distributors, including Disney, Paramount, Sony, the BBC and Media Prima, and it’s subtitled or dubbed in each country’s languages.

The elevator pitch for a potential investor might begin with “the Netflix for emerging markets”. But Grove and Iflix chief executive Mark Britt rush to clarify why Iflix is not really like Netflix and why the US service isn’t their main rival. Pirated content is. They estimate that people in emerging markets spend roughly $6 billion a year on counterfeit DVDs. And that doesn’t include losses from online video channels streaming unauthorised content and illegal downloads from “torrent” sites. “We want to revolutionise internet TV,” Grove says. “When I look at the ecosystem of piracy, YouTube, free internet TV, cable, it’s such a broken system. It’s going to take 20 years, but I think we can revolutionise how movies and TV are consumed over the internet in emerging markets.”

Grove is only 41, but it seems like he’s been around forever. The dotcom baby who in 2000 went bust eventually crawled his way back into the online world. Living his motto of ‘Disrupting Things Daily’ (it’s the tagline on his emails), he launched four Malaysian companies on the Australian Stock Exchange and one on Bursa Malaysia. In November 2015, he and other investors sold one to a News Corp company at a valuation of $534 million. With his stakes in Iflix and three other online companies under his Catcha Group, plus the cash from various sales, Grove ranks No 35 on Forbes Asia’s list of Malaysia’s wealthiest. His estimated net worth is $400 million.

[qt]I love creating disruptive companies with talented people. I want to be great at it. It’s the sport that I play.[/qt]

The Iflix pitches have raised at least $180 million from outside investors, including a $100 million infusion expected to be announced any day. Kuwait’s Zain Group, Los Angeles-based Evolution Media Capital and Catcha itself contrib- uted to this round, along with Europe’s Sky TV, which upped its stake after kicking in $45 million last March. Grove says Iflix’s valuation is now “north of $500 million”.

But hundreds of millions more will be needed. “The cash burn in [subscription video] cannot be underestimated, especially in content costs,” says Vivek Couto, executive director of Singapore research house Media Partners Asia. “Through various rounds you probably have to spend at least $500 million to start to approach break-even in Southeast Asia.” And that doesn’t include Iflix’s plans to invade markets in South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Grove and Britt won’t say how much they believe they need to raise. They also won’t talk publicly about the size of Grove’s stake, how much revenue they expect to generate this year and how big a loss will be incurred. Couto reckons that if total subscription-video revenue in Southeast Asia reaches $120 million this year, Iflix’s share might be 35 percent, or $42 million.

Subscription-video revenue worldwide might reach $25.7 billion by 2021, according to London-based Digital TV Research, and the race is on to capture chunks of this business. In East Asia, Iflix faces rivals backed by heavyweight players such as Singtel-Sony’s Hooq, PCCW’s Viu and others. None of them, however, is publicly striving for 1 billion subscribers by 2020, as Iflix is. (It has only 4 million now.) It may take years, but Grove and Britt believe that aside from two or three giants, there will be just a few smaller global outfits providing a less expensive, local array of content to the new middle classes of developing countries. Iflix plans to be one of them and to dominate in more than 50 markets around the world.

The analogy may be the ride-hailing industry. The assumption in the US was that in its expansion overseas, Uber was invading virgin markets and would be encountering little local competition. That turned out not to be true. Now US investors see Netflix as the pioneer as it expands abroad, but it’s finding local rivals already in place. “As long as you can execute faster and nimbler, you’ll always build a better business than the American that everybody fears is coming to these markets,” Grove says. “We’re customised for each market. We’re appealing to every demographic. In Indonesia, 50 percent of our movies and shows are Indonesian. Pakistan and Indonesia are both Muslim countries, but only 20 percent of their Iflix content overlaps.”

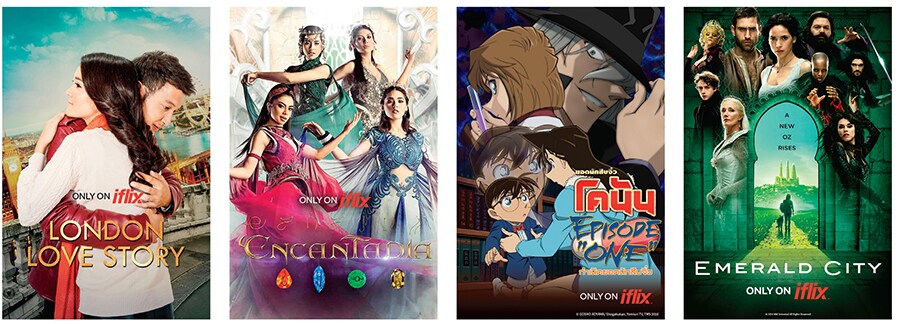

All too familiar with erratic internet speeds in parts of Asia, Grove has insisted since Iflix’s first national launches in 2015 that the service offer an alternative to streaming: Videos have to be downloadable to a phone or tablet for offline viewing on those devices or on a TV. The download feature is something that he says Western companies, assuming that a single concept will work everywhere, might not think of: “We were the first ones in the world to do downloading.” Netflix, which had entered most of the world’s markets by early last year, introduced the feature only last November. Iflix’s most popular titles, from left, in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia. Iflix works with government regulators and censors before launching around the world

Iflix’s most popular titles, from left, in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia. Iflix works with government regulators and censors before launching around the world

Netflix launched simultaneously with one-month free trials in nearly every country it hadn’t entered yet—without government approvals, going through censorship boards or considering technological hurdles with payments and streaming—and encountered something of a backlash. Netflix did not respond to requests to comment.

In contrast, Iflix works with government regulators and censors before launching in each country. For Vietnam, which Iflix plans to enter in the next few months, this has entailed getting censors’ approval for every episode of every TV series. Iflix plans to follow the Netflix model, however, by creating its own local TV series and movies. Iflix Arabia will launch the first two Iflix productions, featuring some top Middle Eastern stars, in coming months. To solve the problem of getting customers to keep finding more shows to watch, Iflix has harnessed the power of celebrities, such as Philippine singer Karylle Tatlonghari, Indonesian actress Michelle Ziudith, Thai comic Note Taepanich and Malaysian musician Afdlin Shauki. They compile favourite playlists and keep their fans updated through social media, and in return they receive small equity stakes in Iflix.

Long before getting into the details of content, pricing and technology, however, Grove and Britt had to convince investors of the potential of their concept. The opportunity was in a young demographic in developing countries that was coming of age with the expectation of video-on-demand, not on a schedule, and whose first and default internet connection would be a mobile device. Markets such as Morocco, Myanmar, Pakistan and Nigeria are very different, says Britt, yet are similar in that “paid-television penetration is low and internet connectivity is leapfrogging ahead—in some instances going from no connection at all straight to 4G”.

Britt, who arrived at Iflix after posts in Australian broadcast TV and at online content outfits, scoffs at the claim that people in countries awash in pirated products won’t pay for the real thing: “That’s a gross oversimplification.” The successes of iTunes and Spotify have shown that people will pay for quality content at the right price, he says. An Analysys Mason survey of 4,000 mobile internet users in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam last year found that a surprising 1,970 had already bought video online. The most popular vendors were Google Play and iTunes, indicating that these were one-off purchases, but they were followed in popularity by Netflix and Iflix, according to analyst Harsh Upadhyay.

[qt] Iflix offers unlimited viewing of 20,000 hours’ worth of movies and TV shows at any time for a monthly fee [/qt]

But investment managers in Australia and Singapore—who had backed Catcha’s successful online-classifieds companies, Iproperty and Icar Asia, and its ill-fated Ensogo ecommerce company—couldn’t grasp this business model or didn’t believe that a local operator could build a global operation. After making 150 calls, Grove found receptive investors in “industry participants”, Grove says, among them EMC, Sky TV, MGM, Indonesian TV operator Emtek and telecoms scrambling for new growth areas. In fact, the first $15 million came from the Philippines’s PLDT, which has both internet service provider and phone divisions.

David Gowdey, managing partner of Singapore’s Jungle Ventures, invested an undisclosed sum in the $30 million Series A round. He says he’s been reassured by the number of executives, directors and advisors who have since come on board, including former chairmen of NBC Universal and Fox Networks. “With Patrick at the helm,” Gowdey says, “Iflix had a strong record of building highly successful and scalable internet businesses across emerging markets. Iflix was purpose-built for the constraints which users too often face—low bandwidth, low credit-card penetration. Iflix will always have competitors, but no-one has assembled an equivalent team so well-placed to compete.”

What about rival technologies? Cable and satellite TV, even where it is available, don’t capture much market share in the countries Iflix is targeting. And Grove doesn’t think telecoms can provide a top content service on their own. But how will legacy free-to-air TV respond? For example, Malaysia’s Astro TV empire has Tribe, an internet bundle of live sports and on-demand content—such as prized new Korean programmes—that over the past year expanded to Indonesia and the Philippines, linking with telecoms there. Britt replies that Iflix already has partnerships with the ABS-CBN and GMA TV networks in the Philippines and is open to any kind of “beneficial partnerships”.

Iflix now has deals with nine telecoms, which typically offer their customers a month- or year-long tryout period, hoping to hook paying customers who then get charged on their phone bill. “Iflix is smart in ensuring they will get paid that way,” says Brett Sappington, senior director of research with Parks Associates. “Getting online payments is difficult in these markets, but telecom companies have figured it out.” Even if they don’t have a credit card or bank account, everyone pays their phone bill, Grove says. Committed to Iflix for the long haul, he says build- ing it to sell to, for example, another Rupert Murdoch property, is not in the game plan. “I want to prove that one of the great global internet companies can come from Asean,” says Grove. “We have no interest whatsoever in selling. That would be like saying to [former US basketball star] Michael Jordan, ‘Here’s $50 million not to play in the finals’.”

Grove always wanted to be an entrepreneur. His proud, vivacious Chinese-Singaporean mother, Diana, is as mystified about the source of this impulse as she is by “computer things”. She recalls taking him to a Toys “R” Us store when he was very young: “He didn’t want toys. He wanted to know if he could buy shares.” Still, for the first ten years of Catcha, contends Grove, his mother held out hope that he’d abandon it in favour of a secure slot in a large Singapore enterprise.

His Australian father, Philip, was a lawyer for US oil company Unocal, which moved him around a lot. So Grove and his two brothers grew up in Singapore, Los Angeles (where he picked up his predominantly North American accent) and Jakarta. He landed in Australia to finish high school and earn a commerce degree from the University of Sydney, running two mobile-phone shops with friends on the side. After graduation, he fulfilled a promise to his parents—who are now divorced his father lives in Sydney—to work in a corporate job for two years, so he put in time at Arthur Andersen in Sydney. He didn’t consider staying longer. It was 1999 and the dotcom bubble was inflating. He headed home to Singapore to join the digital gold rush.

With an old friend, Luke Elliott, he co-founded Catcha Group in June 1999. Working like Yahoo portals, the six Catcha sites in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and Australia had search engines in local languages. By the following April, the Catcha team was in Hong Kong on the second day of a five-day, $32 million fundraising road show, having already raised $20 million. They were selling blocks of shares to big investors before an initial public offering, and a listing on the Singapore Stock Exchange was five days away. Then the Nasdaq began sliding fast. The road show was halted, Asia tech stocks plunged, and Catcha’s IPO was shelved. The company was already $2 million in the red, the bulk of the debt owed to ad agencies and “every TV station in Southeast Asia” for its big advertising campaigns.

While the directors and other grown-ups advised filing for bankruptcy, Grove reasoned that creditors would prefer to get repaid in full in three years rather than five cents on the dollar right away. He went off on a personal road show to make his case. He laughs at his audacity now, but still maintains that “passion should come before a business plan.” Despite reams of bad press coverage of Catcha’s woes, the creditors agreed. The company’s 300 staff members in six countries were quickly pared to 25 in two countries, Singapore and Malaysia, and the headquarters moved to Kuala Lumpur in 2001.

With their last few dollars, Grove and Elliott bought a faltering Singapore lifestyle magazine, Juice, which complemented some of their online content. Over the next few years, they operated local licensed editions of titles such as Hello! and even franchised their own magazines in the region. The foray into print for these two digital mavens paid off. The magazines’ ad revenue not only covered the dotcom debt but subsidised seven years of failed online businesses.

Their internet luck turned only slowly, with a 2007 stake in a Malaysian real estate portal. The Catcha media arm lives on it’s now called Rev Asia, and it listed on Bursa Malaysia in 2011. Today it runs five online sites, but as of this year, it is out of the print business.

The move to Kuala Lumpur was prompted by costs: Salaries and rents then and now are about one-third of those in Singapore. Catcha’s current staff count of 2,000, its highest ever, is dispersed through 35 countries, but there are no plans to relocate headquarters again. In fact, Grove has become a keen booster of Malaysia as a habitat for tech startups. He cites a supportive government, decent infrastructure and English-language universities that attract multilingual overseas students. And in contrast to Singapore, he says, there just aren’t many jobs in multinationals or large state enterprises for the smartest Malaysian graduates. Perhaps most significantly, there is the boleh (“can do” in Malay) mindset, he adds.

“Malaysians, especially Chinese and Indians, know from an early age they can’t rely on the government. They know they have to study hard, work hard. They think, ‘Maybe I’ll start my own company’. The boleh mindset is the opposite of being spoilt.”

Grove’s berth on the list of Malaysia’s richest hasn’t spoilt his drive. As with many an entrepreneur, he works seven days a week because he enjoys what he does, as he told the videographer from the tailor shop. Catcha, of which he owns 80 percent, now owns a secluded house on a Bali beach. Otherwise there are no flashy toys, artworks or fashion statements. His 2013 marriage to Philippine-American singer Krista Kleiner lasted a bit over a year (“too long”). Despite the hopes of his mother, another marriage is not on the horizon.

What’s always on the horizon is another flight. “I love flying.” Every one-and-a-half days, he’s on a plane to somewhere in Southeast Asia. Every two or three weeks, there’s a long-haul flight—nowadays often on a fundraising trip. Flying is a great pleasure because it frees him from the interruptions and meetings of office life. While he never watches a movie on a plane, he might read one of the business biographies he always has on hand in an e-reader a recent favourite was a profile of Softbank’s Masayoshi Son, Aiming High.

And flying enables him to think of the big picture, which he regards as his main role at Iflix and Catcha. He calls himself a lousy CEO his management philosophy consists of hiring the right CEOs and leaving them alone. At the moment, he’s mulling whether Iflix should somehow be involved in delivering sports content. He says he enjoys playing and watching soccer, but that’s not what he considers his main athletic endeavour. He says, “I look at entrepreneurship as my sport. I do this because I love creating disruptive companies with great, smart, talented people. I want to be great at it because I am a competitive person. It’s the sport that I play.”

First Published: Apr 04, 2017, 07:06

Subscribe Now