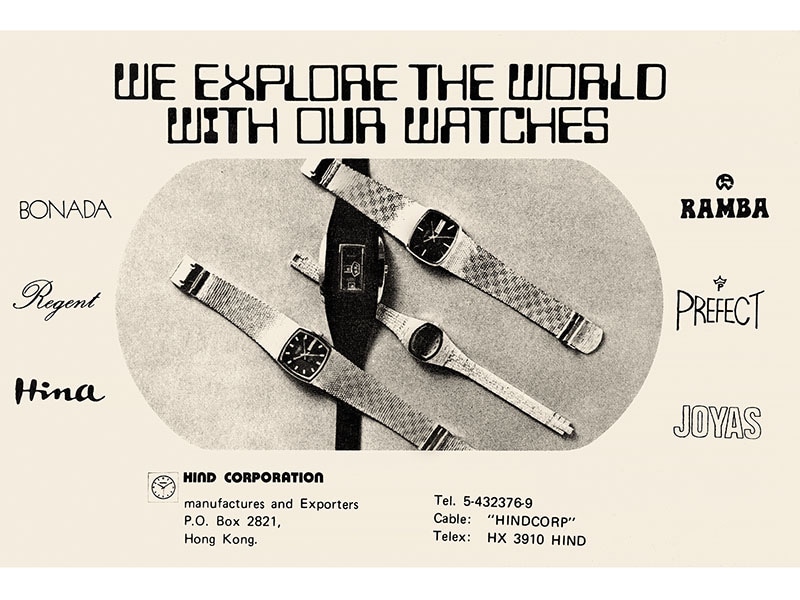

Not all watches, of course, as the luxury market remains robust. But demand would plummet for the mass-market watches produced by his family, among Hong Kong’s biggest manufacturers. It had churned out some 500,000 watches a month for decades. “We liquidated everything,” says Girish’s older brother, Surya Jhunjhnuwala. “The decision was very painful, as our dad had built up the business since 1953. This was his legacy. But it was the right decision, and we both knew it was time. Many others in the industry lost money by hanging on. We had to reinvent ourselves.”

After time ran out on the watch business, the two brothers moved into property and hospitality. Both developed serviced apartments, but after yields peaked, they turned to hotels and are now riding the current hospitality and travel boom. They each run a hotel chain that began by offering hip boutiques packed with pop art and geared toward younger travellers. Now they have stepped up operations, targeting bigger properties for renovation and refitting them with features such as free mini-bars, happy hours for social networking and avant-garde interior designs. There’s ample competition. “A lot of big hotel brands have collections of these quirky hotels, like Accor’s MGallery collection,” notes Bill Barnett, managing director of Asia consultancy C9 Hotelworks. But Girish isn’t fazed: “We are more nimble than the big brands. We’re always experimenting.”

The two run their businesses under the Hind Group umbrella. Surya, 57, lives in Singapore, where his Naumi Hospitality boasts its flagship hotel. Bullish on New Zealand, he opened a 193-room airport hotel in Auckland last February, and up to four more hotels around the country are in the works. Girish, 55, remained in Hong Kong, where his Ovolo Hotels has four properties, including a pair under the Mojo Nomad brand. It’s growing quickly in Australia and is tracked as a rising star in the industry. Privately held Hind won’t release revenue or profit figures. But a company spokesman says it values its net assets at $800 million and, with its expansion plans, should reach $1.15 billion by 2020.

Reinvention is a tradition for this family of entrepreneurs, Marwaris originally from Rajasthan, India. Surya’s and Girish’s grandfather moved as a child to Burma (now Myanmar), where he became one of the biggest textile merchants before his family was forced to flee the country, twice. First it was by foot back to India in 1942 under the Japanese occupation during World War II and then in 1961 it was to Hong Kong, after first a socialist government and then a military government nationalised many industries and confiscated his family holdings. After his father became terminally ill, Surya moved to Singapore in 1997 to redevelop the site of an old hotel that was in the family it was sold to DBS Land in 1999.

Girish has been running hotels for less than ten years, but today he has ten properties and plans to nearly double his room count within two years. This year Ovolo opened two properties in Brisbane and one in Canberra, plus another Mojo Nomad in Hong Kong. Each hotel is different, but shares a brash design, eclectic artwork and pop music, all passions of the boyish chief executive. Everything is up-tempo, with elevators showing classic videos from Michael Jackson to Nirvana. ![g_111589_hind_280x210.jpg g_111589_hind_280x210.jpg]() An observation in the 1990s led to a revelation. “I knew the time was up for watches,” says Girish Jhunjhnuwala“He’s recognised for doing something different with his boutique hotels,” says Robert Hecker, managing director of the Singapore office of hospitality consulting firm Horwath HTL. Girish speaks often at conferences, and Hecker recalls seeing him on a panel called Rebels with a Cause. “They aren’t cookie-cutter properties in any way.”

An observation in the 1990s led to a revelation. “I knew the time was up for watches,” says Girish Jhunjhnuwala“He’s recognised for doing something different with his boutique hotels,” says Robert Hecker, managing director of the Singapore office of hospitality consulting firm Horwath HTL. Girish speaks often at conferences, and Hecker recalls seeing him on a panel called Rebels with a Cause. “They aren’t cookie-cutter properties in any way.”

Both brothers share an appreciation for pop art and disdain for the conventions of the hotel industry. At Naumi’s head office in Singapore, Surya’s meeting room features a large portrait of Salvador Dali, framed by pop-art paintings of rock stars David Bowie and Prince. Ovolo’s headquarters in Hong Kong is even more flamboyant, with a huge mural of Bowie and Prince, plus the Beatles, Bono and Mick Jagger. Guitars and CDs are everywhere, giving it the feel of a 1980s music fan’s clubhouse. And while Girish’s home in Pok Fu Lam is tastefully decorated with Indian antiques, he has a basement hideaway with a wine cellar, monster sound system and, on one wall, the poster of the movie Grease. Except, instead of John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John, it shows Girish and his wife, Sarika Jhunjhnuwala.

The home is in a green suburb of Hong Kong, better known for university professors and artists than high-powered executives. But actually, it’s the old Jhunjhnuwala family home. Girish bought a neighboring house and combined them into a large home for their three children.

Both CEOs are family men and bedrocks in the sizeable Indian communities in Singapore and Hong Kong. Rang Mahal, a flashy Indian restaurant in Singapore, is run by Surya’s wife, Ritu Jhunjhnuwala. They also have three children. Their son, Gaurang Jhunjhnuwala, oversees Naumi’s Australia and New Zealand expansion. The daughters are married and live in India. Girish’s wife was also in the restaurant business, and her interest in Indian food paved the way for the Hind transition to hospitality. Sarika was looking for a place to rent for a restaurant and liked a commercial building in Central. Girish noticed the building was for sale. Flush with cash from the sale of the family’s watch business, he bought the building.

He says he initially planned a hotel but learnt that Hong Kong, awash in hotels, lacked serviced apartments. He refurbished the property into 22 units, each with an unusual design, and it opened in 2002. “I was naïve and thought people would take them up right away,” he says. “People looked, and liked, but nobody was renting.” Now short of cash and with no industry track record, banks wouldn’t lend him more money, so he had to mortgage his house. “That was a major disaster,” he recalls. Fortunately, the market picked up, and his hip apartments proved popular. “That taught me a lot, especially about patience. When you do something novel, it just takes time.”

The brothers’ ambitious grandfather wasn’t much for patience, either. The Hind story traces back more than a century, when at 14, Birajlal Jhunjhnuwala was taken to Yangon (then Rangoon, in British Burma). Dirt-poor after being raised by foster parents in India, he worked for pennies a day at odd jobs and a fabric shop. But within only six years, in 1918, he started his own textile shop later he opened the first mill in Rangoon.

After the war he returned to Burma, and his son Shyam Sundar joined the business as a teen. The fifth of eight children, he proved to be an adventurous salesman and entrepreneur, establishing offices overseas that were crucial for importing fabric and later for the family’s survival. “He travelled all the time, often for months on end,” recalls Surya. “As an entrepreneur, he was fearless.” The family estimates that by the late 1940s, its collection of garment factories controlled 85 percent of Burma’s textile trade.

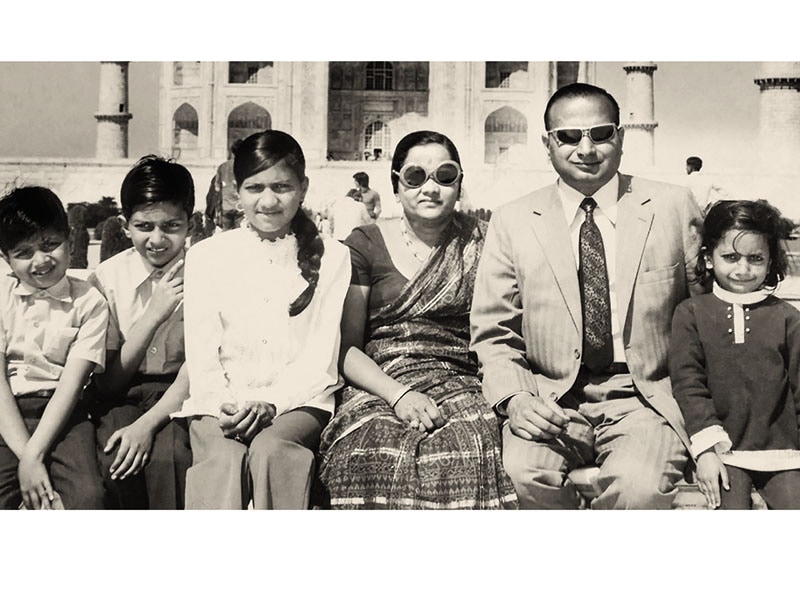

Birajlal died in the late 1950s, and a few years later the family fled to Hong Kong, where it had set up an office. There Shyam Sundar had already explored exporting items such as electronics. “He would trade anything,” says Surya. “He could always spot opportunity.” The city’s textile industry was already well-developed, so he moved into the watch trade and quickly became one of the dominant players. After school and on weekends, the brothers helped assemble watches in a shop on Hollywood Road. Later, their father expanded by opening a factory in Aberdeen, on the other side of Hong Kong island, assembling watch movements under a joint venture in Guangzhou in 1978, and then in 1989 opening its own factory in Dongguan to assemble watches. “It was a totally different world,” recalls Surya. ![g_111587_family_280x210.jpg g_111587_family_280x210.jpg]() “He was fearless. He would trade anything,” says Surya of his father, Shyam Sundar (in sunglasses)Surya opened his first hotel in Singapore in 2007. Both brothers have shown a talent for spotting underdeveloped assets. They don’t build new properties, but acquire poorly performing hotels or forlorn buildings, remodelling them into modern hot spots. But since Girish converted that serviced-apartment building in Hong Kong into his first hotel, the brothers have increasingly committed their attention and capital to expanding their brands. Owning all the buildings while also operating the brands can limit a chain’s growth, however, and Girish is looking at bringing in capital, making large acquisitions and finding other ways to expand.

“He was fearless. He would trade anything,” says Surya of his father, Shyam Sundar (in sunglasses)Surya opened his first hotel in Singapore in 2007. Both brothers have shown a talent for spotting underdeveloped assets. They don’t build new properties, but acquire poorly performing hotels or forlorn buildings, remodelling them into modern hot spots. But since Girish converted that serviced-apartment building in Hong Kong into his first hotel, the brothers have increasingly committed their attention and capital to expanding their brands. Owning all the buildings while also operating the brands can limit a chain’s growth, however, and Girish is looking at bringing in capital, making large acquisitions and finding other ways to expand.

Conventional wisdom suggests that combining their efforts into a single hotel chain would maximise efficiency and profits. But little about their operations is conventional. They share the risks and profits 50-50, even though one chain is bigger than the other. “We incentivise each other,” says Surya, who notes that their different styles are helpful in making decisions. “We consult each other all the time,” adds Girish.

Surya is the classic first son, a careful investor with an astute eye for value. Girish is more brash, the middle child—there are also three sisters—with a long attention span and capacity for risk.

Surya anticipated growth in New Zealand, among the world’s best-performing hotel market in recent years. He’ll add two Wellington hotels next year, and two more—in Auckland and Christchurch—are under discussion. A Sydney property is expected to come online in 2020, and a Melbourne hotel is being considered. Surya says he’s also keen on properties in Europe.

Girish has ramped up in recent years, remodelling an old factory in a forlorn area of Hong Kong into Ovolo Southside, which opened just as the area began to gentrify. He, too, is looking at Europe, but also the US. “I think we’ll get to 2,000 rooms by 2020,” he says, “but it’s not really about room count, it’s about the right numbers.” Ovolo has 1,200 rooms now.

Industry sources are impressed with Ovolo’s design, but note that the hotels are usually small to medium-size. A lack of scale has doomed many innovative boutique brands, and competition has grown more intense as major chains offer their own quirky hotel collections. “The big brands can’t think like us,” maintains Girish. “Every property I’ve bought, my gut tells me to go for it. I’ve learnt to follow my instincts.” So far that’s guided three generations of this family of entrepreneurs.

Girish and Surya Jhunjhnuwala say they have had to reinvent themselves

Girish and Surya Jhunjhnuwala say they have had to reinvent themselves An observation in the 1990s led to a revelation. “I knew the time was up for watches,” says Girish Jhunjhnuwala“He’s recognised for doing something different with his boutique hotels,” says Robert Hecker, managing director of the Singapore office of hospitality consulting firm Horwath HTL. Girish speaks often at conferences, and Hecker recalls seeing him on a panel called Rebels with a Cause. “They aren’t cookie-cutter properties in any way.”

An observation in the 1990s led to a revelation. “I knew the time was up for watches,” says Girish Jhunjhnuwala“He’s recognised for doing something different with his boutique hotels,” says Robert Hecker, managing director of the Singapore office of hospitality consulting firm Horwath HTL. Girish speaks often at conferences, and Hecker recalls seeing him on a panel called Rebels with a Cause. “They aren’t cookie-cutter properties in any way.” “He was fearless. He would trade anything,” says Surya of his father, Shyam Sundar (in sunglasses)Surya opened his first hotel in Singapore in 2007. Both brothers have shown a talent for spotting underdeveloped assets. They don’t build new properties, but acquire poorly performing hotels or forlorn buildings, remodelling them into modern hot spots. But since Girish converted that serviced-apartment building in Hong Kong into his first hotel, the brothers have increasingly committed their attention and capital to expanding their brands. Owning all the buildings while also operating the brands can limit a chain’s growth, however, and Girish is looking at bringing in capital, making large acquisitions and finding other ways to expand.

“He was fearless. He would trade anything,” says Surya of his father, Shyam Sundar (in sunglasses)Surya opened his first hotel in Singapore in 2007. Both brothers have shown a talent for spotting underdeveloped assets. They don’t build new properties, but acquire poorly performing hotels or forlorn buildings, remodelling them into modern hot spots. But since Girish converted that serviced-apartment building in Hong Kong into his first hotel, the brothers have increasingly committed their attention and capital to expanding their brands. Owning all the buildings while also operating the brands can limit a chain’s growth, however, and Girish is looking at bringing in capital, making large acquisitions and finding other ways to expand.