How Divesh Makan gained entry into Zuckerberg's inner circle

Not all financial advisors are created equal. Meet Divesh Makan, consigliere to Silicon Valley's brightest billionaires

In the hierarchy of the investment business, stockbrokers have long occupied a spot near the bottom of the food chain. They are the hunters and gatherers, knocking on doors to bring in assets that earn small fees while the bigger fish arrange the headline-grabbing deals and score life-changing bonuses.

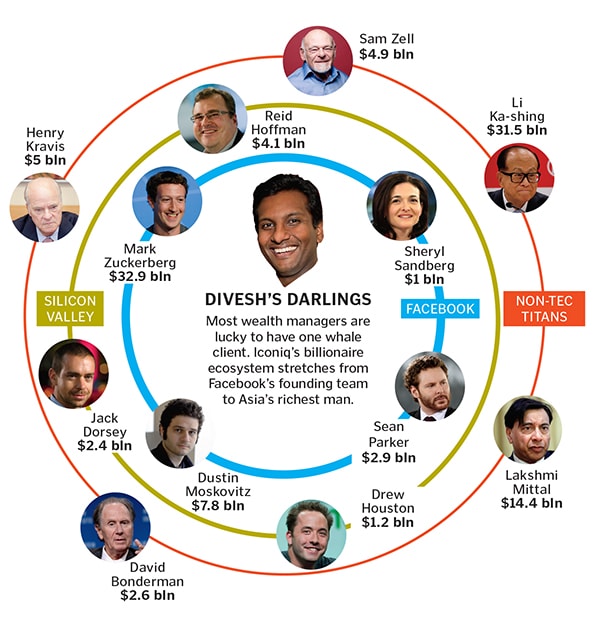

But among the throngs of brokers, who now prefer the moniker “wealth manager”, few have cultivated a client base and model like Iconiq Capital, an obscure Silicon Valley firm headed by an irrepressible Indian from South Africa named Divesh Makan. Makan, 41, has turned his otherwise run-of-the-mill registered investment advisory into an exclusive members-only Silicon Valley billionaires club that operates as a cross between a family office and a venture capital fund. His most famous client and the key to his success is billionaire Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, whom Makan met in 2004 when he was a broker at Goldman Sachs.

Working his way into Zuckerberg’s inner circle when Facebook was still in diapers has proved to be a gold mine for Iconiq. Already it has full discretion over $1.4 billion in client funds and advises on another $7.6 billion. Yet Iconiq’s advisory services represent only one thread of the dealmaking web Makan has woven thanks to the abundance of Zuckerberg cronies on his client roster, including Facebook’s Dustin Moskovitz and Sheryl Sandberg, Twitter’s Jack Dorsey and LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman. His board of directors is another power list, with non-tech titans like Henry Kravis and David Bonderman, Chase Coleman and steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal’s son Aditya.

Makan’s wealth management approach flies in the face of widely accepted post-Madoff best practices for advisors, which preach strict adherence to corporate protocols and regulatory rules. He is a throwback to the early days of Wall Street, when dealmakers like Goldman Sachs’ Sidney Weinberg blurred the lines between business and pleasure and turned the art of schmoozing into a powerful and profitable investment banking network.

Indeed Makan shuns the title of wealth manager, according to those who have worked with him. He sees himself instead as part do-it-all financial consigliere, part deal broker/venture capitalist and part human Rolodex. Makan’s currency is access and relevance. While Silicon Valley stalwarts like Sequoia and Benchmark can point to a long list of successful IPOs and a deep bench of management experts, he hawks the “Zuck & Friends” brand to piece together deals between young startup entrepreneurs and billionaire sugar daddies, as well as between the billionaires themselves.

The centrepiece of this action is Iconiq’s $500 million Strategic Partners fund, Makan’s flagship among 39 private investment vehicles, which total about $1 billion. The firm claims only 100 family office clients, but regulatory forms report some 300 investors, who put pre-IPO money into such companies as Alibaba and India’s ecommerce giant Flipkart. Key to Makan’s pitch is bowling over wannabe Zuckerbergs with raw star power. Before Iconiq led a $40 million Series D round last May for social media software firm Sprinklr, Makan invited founder Ragy Thomas to dinner with three famous billionaires.

“When someone like Iconiq wants to invest, you can’t say no,” says Thomas. “They can probably connect to anyone in the world.” Aaron Skonnard, co-founder of e-learning startup Pluralsight, received a similar “join Silicon Valley’s inner circle” pitch from Makan before Iconiq participated in the firm’s $135 million Series B round.

“They don’t want operational involvement,” says Skonnard. “They just want to connect and network and give more access.” He and his wife recently flew in to San Francisco from their home in Salt Lake City for a quarterly Iconiq networking event “where all the magic happens”.

While Makan and his team sell entrepreneurs on access to its famous clients, they sell other connections on getting in on the ground floor of hot startups. Billionaire moguls like Sam Zell and Li Ka-shing have massive real estate portfolios but no direct link to the Silicon Valley in-crowd. Through Iconiq they have gained access to startups that Makan & Co advertise as being “approved by Zuckerberg”. What does Makan ask for in return? Opportunities for his clients to invest alongside Zell and Li in their deal flows.

As a registered investment advisor Makan has a fiduciary duty to “not engage in any activity in conflict with the interest of any client”. But unlike your average Merrill broker, who faces a gauntlet of compliance hurdles on every product mentioned, Iconiq deals practically advertise their dizzying array of conflicts of interest. Take Iconiq’s 2013 investment in SurveyMonkey, in which Makan blurred the lines between investment advisor, limited partner and friend. He put clients like Dropbox’s Drew Houston, Quora’s Adam D’Angelo and LinkedIn’s Jeff Weiner in the $800 million round. But SurveyMonkey CEO Dave Goldberg and his wife, Facebook exec Sandberg, are also clients and confidants of Makan, and Goldberg sits on Iconiq’s board. The SEC frowns on advisors engaging in such conflicts but will tolerate it as long as it’s disclosed.

Like other wealth managers, Iconiq charges percentage-of-assets fees: Up to 1.5 percent on allocations in stocks, bonds and ETFs. But it takes additional performance fees of 20 percent to 30 percent on venture fund profits. Not wanting to miss out on the action, Iconiq itself co-invests with its clients on the deals they arrange.

Makan shuns publicity and goes as far as to require clients to sign non-disclosure agreements. Though Iconiq refused comment, Forbes’ investigation was stitched together from dozens of interviews with those in and around the firm. Many requested anonymity, fearing they would be shut out of Makan’s club.

The seeds of Iconiq’s controversial family office/VC approach were planted in the summer of 2001. With an electrical engineering degree from South Africa’s University of Natal, a management consulting stint at Accenture and a Wharton MBA, Makan thought he’d make his career in investment banking or private equity. But the dot-com crash and recession forced him into a retail sales job in Goldman Sachs’ San Francisco wealth advisory office. Makan rarely handed out business cards—distancing himself from the vanilla “wealth advisor” label—but he worked hard to ingratiate himself to young moguls, finding clients before they became household names. Sandberg and Goldberg joined his roster two years before Google’s IPO, and he hooked up with Zuckerberg and Sean Parker shortly after Facebook moved from a Harvard dorm to Palo Alto. Makan inspired loyalty by referring clients to each other as much as they referred new ones to him. For example, he recommended Sandberg to Facebook.

In the early days Makan would volunteer as a gofer for everything from meeting with estate planning lawyers to buying an engagement ring. “Divesh will tell clients everything but ‘I’ll pick up your laundry,’” says one venture capitalist. In an interview in a 2007 issue of Families in Business magazine, Makan bragged that he had planned a stag party in Las Vegas, edited business school applications for clients’ kids and even served as a marriage broker. Money management was but a small part of the job. “People care a lot more about us running their life. They want us to look after them,” he said at the time. Makan’s full-service approach clashed with the rigid structure of traditional Wall Street firms, alienating colleagues and compliance officers alike. He left Goldman in 2008, telling people it was over a workplace disagreement, but Goldman officially describes the reason for termination as a “loss of trust”. Either way he landed on his feet with a reported $20 million signing bonus at Morgan Stanley, thanks to an assist from Sandberg, who vouched for him. Goldman co-workers Chad Boeding and Michael Anders followed.

They had more freedom at Morgan Stanley but still clashed with higher-ups over the limits to their off-the-books behaviour.

Finally, in 2011, with the Facebook IPO imminent, Morgan Stanley devised a plan to create an in-house family office around Makan. According to former colleagues, Makan & Co walked into a meeting and stated their intent to take the model outside the firm. Not wanting to anger Zuckerberg on the eve of Facebook’s IPO, Morgan Stanley quietly let the three-man team strike out on their own. These days Iconiq reports that it is closed to new clients, yet it still actively pitches entrepreneurs developing hot apps. The relationship starts with financial advice but often morphs into grabbing a stake in their companies for Iconiq and its best clients. “Divesh is following a time-honoured path,” says Matt Harris, managing director at Bain Capital Ventures. “Goldman has 12 different businesses, and they’re all opaque. If a company is raising money, they help them raise it, they take fees from them and [they also take fees] from the clients they got to invest.”

Competitors like Bruce Brugler, of $4 billion Presidio Group, marvel at Makan’s success. “Iconiq is clearly conflicted, but that’s their model. And it doesn’t seem to slow them down.” What could disrupt Iconiq’s growth trajectory is a severe downturn in the overheated market for tech stocks and IPOs.

“They’re making a huge bet on the continued bull market, the sex appeal of a ‘Friends of Zuckerberg’ fund and co-investments that could make them look like heroes,” Brugler says, “but they haven’t been through the down cycle yet.”

A few clients, like Zynga’s Mark Pincus and Facebook’s Chris Hughes, have pulled money out of the firm, but Iconiq continues to reel in new let’s-make-a-deal clients.

The lure of tech billionaire connections was even dangled in front of Forbes. Iconiq’s spokesman twice offered us “inside scoops” in exchange for dropping our story. Makan “would be a lot more valuable as an asset you could call all the time,” we were told. “With his connections, Divesh could be a great friend.”

First Published: Jan 05, 2015, 05:31

Subscribe Now