Ashton Kutcher, one of the world’s highest-paid TV actors, can obviously afford that most essential of Los Angeles celebrity luxuries: A car and driver. But he still prefers Uber. “We’re going to go to Warner Bros,” he dictates, as we hop into a black Chevy Tahoe with Kutcher’s business partner, music manager Guy Oseary, in Beverly Hills. “So we’ll go to Moorpark and then hit the 101.”

There’s no need for directions. Our optimal route, from the gated enclave where Kutcher and Oseary live three doors apart to the lot in Burbank where the actor is filming his new Netflix series, is already programmed into the driver’s phone. But the ever confident Kutcher can’t help himself in this car, he’s the boss. Five years ago, Oseary and he invested $500,000 in Uber—that stake is now worth 100 times what they paid.

“You’re not even actually taking on the taxi companies—you’re taking on the notion of owning a car,” says Kutcher. “That’s crazy. And that’s why it has the velocity and potential that it has.”

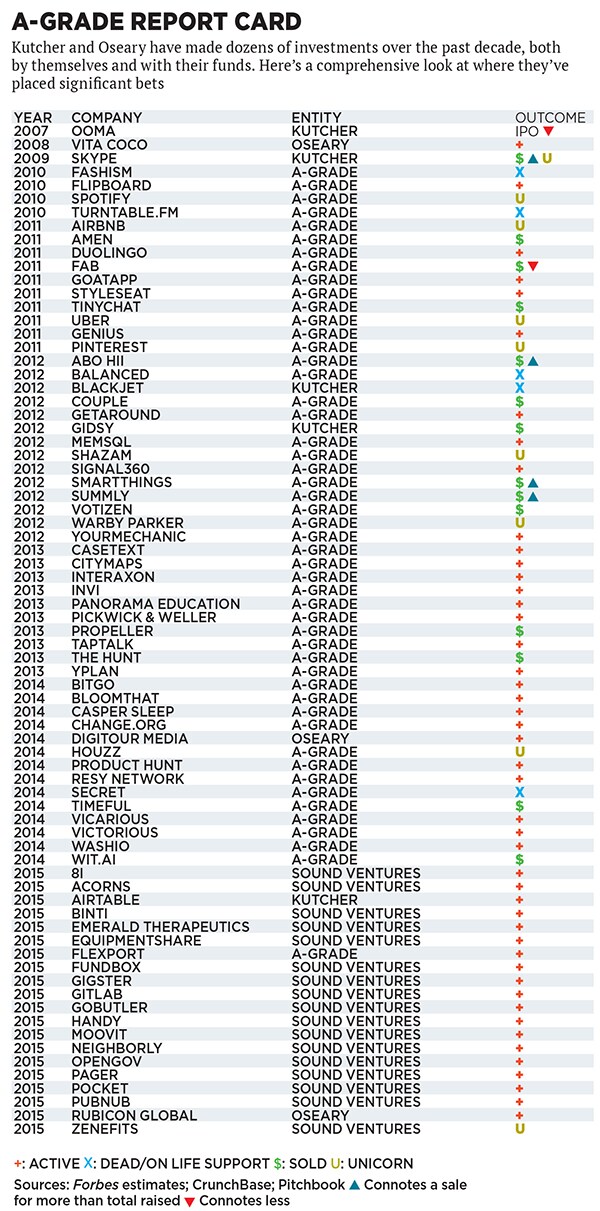

It would be easy to chalk that up as one lucky bet. William Shatner, after all, never has to work again after hitting it big with Priceline, and no one’s going to confuse Captain Kirk with Kirk Kerkorian. But Kutcher’s and Oseary’s portfolios, which number more than 70 investments combined, include a roster of grand slams way past Uber—Skype, Airbnb, Spotify, Pinterest, Shazam, Warby Parker—with valuable startups like Zenefits and Flexport still gestating.

It would also be easy to write off Kutcher, 38, and Oseary, the 43-year-old manager of U2 and Madonna, as amateurs who trade coolness for deal flow. Except that a slew of self-made billionaires—including Ron Burkle, Eric Schmidt, Mark Cuban, David Geffen and Marc Benioff—gave them millions from their personal stashes to invest. And while those five have all been known to enjoy the taste of fame and glitz, a decidedly more staid backer, Liberty Media, recently tossed them $100 million to put to work—and to do so without Burkle, who until now has partnered actively with them.

As a public company, Liberty Media must live and die by its numbers. And that’s precisely what makes Kutcher and Oseary so compelling. They opened their books to Forbes, and the numbers are a lot more impressive than Dude, Where’s My Car? Over six years they’ve turned their $30 million fund into a cool $250 million. The guy who until recently starred in Two and a Half Men has generated almost 8.5x.

“If you can routinely return 3x, you’re considered one of the best venture capitalists,” says Marc Andreessen, a Midas List regular who’s raised more than $4 billion over the years with his firm, Andreessen Horowitz. “If you can return 5x, it’s considered to be a home run. I took my math classes: 8x is seriously higher than 5x.”

Andreessen isn’t alone in his appreciation. Talk privately with the heavies in Silicon Valley who have spent time with Kutcher and Oseary and watched them in action, and you hear and see the same story: These guys are legitimately smart. No “for Hollywood types” caveats. Their surprising success underscores two universal truths: How simple it is to manage other people’s money and how hard it is to do it well.

The strange road of Ashton Kutcher, venture capitalist, starts with a now bankrupt rapper: Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson. A decade ago, 50 Cent took an equity stake in Vitaminwater parent Glaceau in exchange for becoming the face of the beverage—and earned an estimated $100 million when Coca-Cola purchased the company in 2007.

“I had done a [traditional endorsement] deal for Nikon at the time,” Kutcher recalls over a California breakfast of eggs and avocados at Oseary’s home. “I’m like, ‘Whoa, hold on, wait a second. I’ve got to figure out how to get in the equity game, because it just makes so much more sense’.”

Everything about Kutcher’s journey has been intuitive. Born to middle-class parents in Iowa, he didn’t grow up with any business know-how or lessons other than the most important: A strong work ethic. He was working construction with his dad by the age of 10 in high school, he had a series of odd jobs, including janitor, butcher and factory worker at General Mills.

The brains were always there: When he enrolled at the University of Iowa, he planned to major in biochemical engineering—until he won a modelling competition, dropped out and moved to New York, then Los Angeles.

His big break came in 1998 with That 70s Show, where he starred as dopey hunk Michael Kelso, followed by a string of similar film roles. But while he was being typecast for stupidity, he began honing his chops. In 2003, he created and hosted a hidden-camera practical-joke show for MTV, Punk’d. By the time his Vitaminwater inspiration struck, he’d founded a full-blown production company, Katalyst. His digital chief, Sarah Ross, whom he’d poached from TechCrunch, began introducing him to Silicon Valley elites, including Ron Conway and Michael Arrington. “I spent 90 percent of my time just listening,” says Kutcher.

“There was definitely a period there in which very, very few people outside the Valley were taking any of this stuff seriously,” says Andreessen. “He started doing it when it really wasn’t cool.”

He learnt his lessons well. Kutcher is fluent in the language of tech startups, and it isn’t just token jargon. At a private dinner at the Forbes Under 30 Summit last year, Kutcher spent a half-an-hour leading a vigorous debate with a bunch of media heavies on the correct ratio to optimise web traffic and digital advertising revenue. He is, in essence, the football jock who started hanging out with the math nerds and eventually demonstrated that he was one of them. “Once you learn how to identify a snow leopard,” says Kutcher, “it’s pretty easy to see a snow leopard coming along.”

Andreessen invited him to plough $1 million into Skype in 2009. When Microsoft bought the company 18 months later, Kutcher’s outlay quadrupled in value. He was hooked. More important, he impressed his new friends in San Francisco, who were still recovering from the Great Recession.

Oseary, meanwhile, was undergoing a similar metamorphosis. Born in Israel, he moved to Los Angeles when he was eight and ended up at Beverly Hills High School, where he started managing small-time hip-hop acts and mingling with the children of Hollywood power brokers like Freddie DeMann. The music manager hired a teenage Oseary to work for him at Maverick Records, the label he co-founded with Madonna. Through the mid-1990s, Oseary rose from talent scout to chairman, overseeing a roster that included Muse and Alanis Morissette.

“A lot of what I do now is very similar,” he says, “which is trying to identify talent and then help them market their music [and] their vision.”

Bitten by the startup bug, Oseary developed a relationship with Bill Gross, who raised over $1 billion for his Pasadena incubator, Idealab, in the late 1990s. But when the market cratered in 2000, it wiped out many of his burgeoning tech companies, along with plans for an IPO—and millions from Oseary, who’d gone all-in on Idealab. To add salt to the wounds, when former CAA agent Seth Rodsky offered him a chance to invest in the same Vitaminwater deal that would enrich 50 Cent and inspire Kutcher, Oseary declined.

Around the same time, he befriended Burkle, who told him the Idealab debacle was a blessing in disguise: He’d learnt a valuable lesson at 27. Oseary soon took over as Madonna’s manager, guiding her to back-to-back world tours that grossed a combined $600 million. When Rodsky came to him in 2008 with a chance to invest in Vita Coco, Oseary wrote a cheque for $1.2 million the company’s valuation has increased from $28 million to $664 million since 2007. Next he scored big again with Groupon. As he began delving deeper into startup funding, he found the entertainment business heavily underrepresented in Silicon Valley.

“There was only one guy from our community that was not just doing it but even kicking my ass and getting in all the right deals,” says Oseary. “It was Ashton.” When Oseary proposed joining forces, Kutcher agreed. "©

Kutcher and Oseary joined with Burkle to form A-Grade Investments in 2010 (the first three letters of the fund represent each founder’s first name). The billionaire contributed $8 million and the use of his back office, while Kutcher and Oseary added $1 million each of their own. A-Grade’s early cheques started out in the $50,000 to $100,000 range, gradually pushing into seven-figure territory. The trio targeted startups with three traits: Appealing founders with whom they actively wanted to work a problem-solving mission statement oriented around saving or enriching time and, finally, a business model that could be boosted by their involvement.

![mg_86523_kutcher_and_oseary_280x210.jpg mg_86523_kutcher_and_oseary_280x210.jpg]()

One of them was the lyrics-and-literature site Genius, formerly known as Rap Genius. A-Grade was the first major investor after the company graduated from incubator Y Combinator in 2011. Says co-founder Ilan Zechory: “Anyone who’s ever fundraised knows how big of a deal that is, and how much investors tend to wait and see what other investors are doing.” Kutcher leveraged his massive social media influence—he holds the distinction of having the first Twitter account ever to top 1 million followers—to drive viewers to the site. As user numbers surged, Andreessen Horowitz invested $15 million in 2012 A-Grade had gotten in at a $10 million valuation, a number that has since increased by a double-digit multiple.

Kutcher’s career turn began attracting attention, albeit as a novelty. (The New York Times dubbed him a “handsome ditz” who “mastered the utopian lingo of Silicon Valley”.) He was most often lumped in with other celebrity investors, the likes of Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga, who knew enough to listen to their managers but not much more. “There are a lot of celebrity ‘tourists’ in our industry these days,” says billionaire investor Chris Sacca, who graced the cover of last year’s Midas List issue. “Famous people lurking around trying to get a piece of the pie but without bringing any value to the table. For Ashton in particular, it’s been a daily commitment to tech for at least eight years now.”

Kutcher represents a first: The celebrity who doesn’t merely take equity for an endorsement or even use his fame to access deals but actually manages money for other people. The A-Grade track record let him do that: In 2011, Kutcher, Oseary and Burkle put $2.5 million into Airbnb, a stake now worth about $90 million. They also placed $500,000 in Uber—one chunk via Sacca’s Lowercase Capital, which got in at seed stage, and another directly in later rounds—now worth north of $60 million.

There were missteps aplenty. Kutcher poured cash into—and briefly became creative director of—web-based phone service Ooma, which cratered after its initial public offering (IPO) he also took a bath on Uber-for-planes app BlackJet. A-Grade invested in online fashion hub Fab.com, watching its value soar to $1 billion on paper, then plummet to a rumoured scrap-heap sale price of $15 million.

But like Hollywood and music, venture capital is a hits business. And even if you take away the Uber and Airbnb jackpots, A-Grade’s performance remains a solid 3.3x, thanks to other winners, including a $3 million investment in Spotify in 2010 (up at least 3x), $300,000 in Warby Parker two years later (up 7x) and $1.5 million in Houzz in 2014 (up 6x).

In 2012, Kutcher, Oseary and Burkle decided to raise more money for A-Grade and found a veritable conga line of billionaires willing to put money in. “Tech startups are hit-and-miss, and I trusted these guys to have more hits,” Geffen tells Forbes. Adds Cuban: “They both have a great feel for what works with consumers.” And while there was clearly a cool factor at play, Kutcher and Oseary also offered a different kind of access—the possibility of getting in on future Uber and Airbnb rounds.

“Whether they were betting on us or betting on the portfolio, there was already upside to be realised,” says Kutcher.

Fame can be smart money when used properly. When New York City tried to restrict Uber’s growth through stifling regulation, Kutcher used his social media reach to publicly blast Mayor Bill De Blasio, who quickly reversed himself. Oseary had his clients, including Madonna, publicly use mobile app Flipboard, another A-Grade investment. Kutcher even earned a scolding from the FTC in 2011 after he plugged a handful of A-Grade holdings in an online issue of the now-defunct Details magazine that he guest-edited.

This high-touch attitude keeps the opportunities flowing. “When you have a reputation for being productive and for being a contributor,” says Andreessen, “then you tend to get invited to a lot of things.”

The next chapter of the Ashton Kutcher venture capital journey can be found at the edge of San Francisco’s tech-friendly SoMa district in a sun-drenched loft recently vacated by AngelList. This is the new home of Neighborly, a municipal bond crowdfunding startup, fresh off a $5.5 million seed round. Peeling paint greets you when you exit the elevator—AngelList ripped out a bicycle-size peace sign and took it to its new digs. In its place, says Neighborly founder Jase Wilson, a 33-year-old MIT grad, will be a framed quote from Ashton Kutcher: “Make bonds sexy again.”

Kutcher and Oseary will manage Liberty’s $100 million in a new vehicle, Sound Ventures. Neighborly is one of its first investments. “They see things from a worldview that we simply, other than them, don’t have many people thinking about,” says Wilson of Kutcher and Oseary. “It’s not just entertainment, it’s not just media. It’s the global connectivity of people.”

“Every single person in our portfolio has our personal phone numbers,” says Kutcher. “They can call us at any point in time, 24 hours a day, whatever it is.”

Sound Ventures is a big step up: More money, other people’s money—Liberty specifically rebuffed Kutcher and Oseary’s offers to put in their own millions—and no grown-up. While Burkle wouldn’t sit down with Forbes, his take on the breakup, by email, reads like this: “We are as close as we’ve ever been and our teams continue to look at deals together.” Adds Kutcher: “Because we’re such good friends, we never wanted different perspectives on the potential market to come into conflict.”

More likely, Burkle, who hasn’t had a boss in years, didn’t want to be told what to do. Liberty has veto power over major investments and will provide back-office support through concert giant Live Nation, in which it is the largest shareholder. It was Live Nation’s chief, Michael Rapino, who introduced Kutcher and Oseary to Liberty CEO Greg Maffei. Kutcher and Oseary confirm that they’re taking a “typical carry”—figure 2 percent of cash invested and 20 percent of profits—plus performance bonuses.

So why would Liberty place this money with Kutcher and Oseary instead of a more established player like Greylock or Sequoia? “They would not have agreed, maybe, to some of the terms,” says Maffei. “But I think, frankly, what is so important is they have a different way, a different world than those other firms.”

Neighborly epitomises this new way. With Sound Ventures, Kutcher and Oseary want to focus on decidedly dull fields. Besides crowdsourcing munis (“Making bonds sexy again”), they’re already invested in human resources automation (Zenefits), financial transparency for local governments (OpenGov) and household service (Handy).

All told they expect to fund 60 to 70 companies over the next few years. To pop that $100 million base, they’ll need to make larger bets at later stages. “Four of them, if we’re lucky, are going to be supernovas, and 50 percent are going to break even,” says Kutcher. “And 25 percent of them are going to fall to the wayside. We didn’t have to explain that to Liberty.”

The deal could get bigger. They’ve lined up TPG Capital to provide additional cash if a portfolio company is looking for a bigger infusion. And Liberty’s wallet seems open, too. “They can always come back and ask for more,” says Maffei."©Heady stuff for Kutcher and Oseary, as they sit in the former’s Burbank dressing room, which he’s packed with Chicago Bears memorabilia, brainstorming about an incubator they might start. Just then a stagehand ducks in and asks if Kutcher is ready to start shooting. He nods. “I’ll be there in two minutes.”

That interruption offers helpful perspective. Kutcher made $20 million in the last season of Two and a Half Men. For Oseary, between recently concluded concert tours of U2 and Madonna, which grossed $152 million and $305 million, respectively, he’ll probably take home $15 million. This is a passion for these guys. It’s not life-and-death.

“If we don’t make a dollar, but we change the world in a meaningful way because we solve real problems and we support great people and do our best to help, the returns are going to be the exhaust of that,” says Kutcher. Spoken like a true Silicon Valley veteran.