How AppNexus CEO Became the King of Ad Tech

Brian O'Kelley came up with a killer web ad platform. All that stands between him and a giant payday are Google, mobile and his volatile personality

Employees at AppNexus, a bustling advertising technology firm near New York City’s peaceful Madison Square Park, don’t often interact with the boss. The five-year-old company, with 547 employees, has been growing too fast for that. Plus, its 6-foot-5, 240-pound CEO, Brian O’Kelley, can be, well, a bit irascible. Office folklore has it that he once threw a stapler at a software engineer. (O’Kelley vehemently denies that version, saying it was a tape dispenser thrown on the floor with no employees present.) And he was forced to resign from his previous job for clashing with the boss and being hard to work for.

On a recent Wednesday O’Kelley confessed to Forbes that one of his staffers had earlier that day burst into tears after a project meeting with him. O’Kelley says the tears came from personal issues, “but I was thinking, ‘Oh God, I’m sensitive to my reputation.’ I know the impact I have on people.”

O’Kelley can be overbearing, and friends say he’s mellowed a bit, but people put up with him and invest millions in him because he’s arguably the most brilliant software engineer in New York’s brimming ad-tech community. He’s known as the inventor of ad exchanges, the massively interconnected bidding systems that account for a growing portion of sales of web banner and rectangle ads.

AppNexus servers process 16 billion ad buys per day and handled an estimated $700 million in ad spending last year, giving it the biggest reach on the open web after Google.

Yahoo and Facebook run bigger exchanges, but they primarily sell their own inventory. But AppNexus’s technology is widely regarded as the fastest and most flexible out there. If there’s an exchange that can rival Google in the $13 billion market for web display ads—and everyone in the industry wants alternatives—it’s AppNexus.

“I believe there will be a natural duopoly in the ad exchange space instead of eight or nine players,” says Bill Wise, CEO of ad infrastructure firm Mediaocean and former president of ad network Right Media. “The two that will emerge are AppNexus and Google.”

AppNexus will take in an estimated $130 million in fees this year, up 85 percent from 2012. Ebay, Microsoft and Facebook are all big partners. The company is not yet profitable but has raised $140 million in venture capital to invest in new products and global growth. In January it was valued at $625 million now it’s likely closer to $850 million. After Tumblr it’s among the most valuable private firms in New York’s Silicon Alley. And it probably would not have happened had it not been for the sizeable chip on O’Kelley’s sizeable shoulder that spurred him to prove doubters wrong.

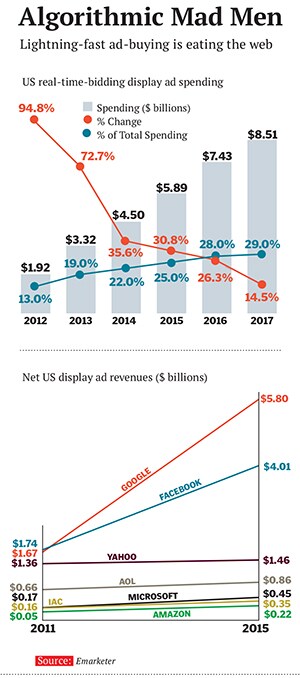

In less than a generation the ad-tech industry has gone from the equivalent of manual placement of banner ads on web pages to continuous auctions in which hundreds of ad-serving decisions are made in the milliseconds before a page loads. The lion’s share of banner ads (as opposed to the much larger search-ad market) are bundled into networks that apply the relevant user-targeting data. These groups of networks in turn form exchanges, giant pools of liquidity allowing publishers to sell their inventory faster and buyers to get a fairer price. The primordial ad-serving tech was created by DoubleClick in the mid-1990s, a firm sold for $1.1 billion in 2005 to private equity firm Hellman & Friedman and eventually to Google for $3.1 billion in 2007.

The most valuable descendant of Double-Click to date has been Right Media, founded in 2003 by DoubleClick executive Michael Walrath (and sold to Yahoo in 2007 for $850 million). Right Media commercialised the first big ad network, but started out as a glorified sales desk. Walrath needed a chief technology officer to build his automated ad network, and he found a brash young consultant and programmer named Brian O’Kelley.

O’Kelley built Right Media’s network but was soon interested in the newer idea of connecting networks to form exchanges. In 2005 O’Kelley hatched a plan to license a version of Right Media’s network to an Israeli software firm called Cydoor so it could bid from within Right Media’s own network. “The first time an auction connected across the two, I shouted, ‘Eureka!’ and no one had any idea what I was talking about,” O’Kelley says. (He calls himself “100 percent” the sole inventor of the exchange others say Right Media’s management team had joined in the idea.)

What’s undisputed is that relations between O’Kelley and Walrath were deteriorating. Walrath says O’Kelley, a perfectionist, refused to delegate enough development and was taking too long to find good people willing to work for him. O’Kelley doesn’t dispute that he was slow to hire high-level engineers but blames long hours in a high-pressure growth environment for the frayed relations.

Several former employees say that O’Kelley’s impulsiveness and outbursts made him a liability in meetings with major partners like Yahoo. “He’s very difficult emotionally to deal with,” one source adds.

“Part of that manifests itself in needing to be the smartest person in the room.” It didn’t help matters any that O’Kelley was in the process of divorcing his boss, Right Media president Christine Hunsicker, who had been mediating between the two strong personalities.O’Kelley was fired in July 2007, one day after Right Media’s sale to Yahoo closed. O’Kelley did fine: His early shares earned him close to $30 million in Yahoo stock. But he took bad advice and held for a year, finally pocketing much less. Nor did he do his memory at Right Media any favours by telling The New York Times in October that the purchase price made him giggle.

O’Kelley immediately started a new venture, a cloud-computing idea that would compete with Amazon Web Services, but ran into doubters, including Redpoint Ventures’s Chris Moore.

“[Moore] said he didn’t believe I could scale a company, that he didn’t think I could hire really great senior people,” says O’Kelley. Others, such as Khosla Ventures, were more willing to bet on O’Kelley, who then started AppNexus in September 2007 with former Right Media exec Mike Nolet.

The cloud-computing idea went nowhere quickly. Potential clients such as Pfizer and Goldman Sachs told him he was too small for serious consideration. At the six-month mark, O’Kelley told the team they had to do something else or die, and that something was to return to the ad-exchange business. Six months later, and exactly one day after his noncompete expired, O’Kelley announced his plan to build a new exchange. Several Right Media employees jumped over to join him.

Right Media had a head start, but AppNexus scored a coup as the first exchange to offer real-time bidding, with eBay as its first customer. With a clean sheet of paper, O’Kelley was able to build a set of much easier tools for handling the fast-paced automation of web display ads. Publishers and other networks could, within minutes, be up and running with other exchanges and networks and customise their auctions on the fly. The arms race against Google and Yahoo was on. In late 2009, O’Kelley stole away the head of Google’s exchange, Michael Rubenstein, to be AppNexus’s president. Microsoft signed up for O’Kelley’s exchange and took a minority stake in October 2010.

Less than two months later, AppNexus knew it had hit the big time when Google temporarily blocked it from accessing its DoubleClick ad exchange. Both companies made nice, but Rubenstein says now that the move was suspicious in its timing: “That was a tense time in our company’s history. After Microsoft endorsed us, Google [may have thought] that might be their last chance to squash us.” (Google declined to comment but has in the past denied it was anything more than a response to a policy violation by an AppNexus partner.)

Squashing is not likely to happen now. AppNexus has scores of happy customers and is the biggest independent exchange apart from Google. Its greatest challenge is in mobile, where consumers are expected to spend as much as 25 percent of their online time next year. O’Kelley is investing $25 million on bringing his platform to mobile, and parts of it are in beta. He admits his company is late because it focussed last year on tools to serve video ads. Google has been hosting mobile trades since 2012, and another mobile exchange, Millennial Media, has already gone public with a current market capitalisation of $680 million.

O’Kelley predicts he’ll build up mobile revenue to 10 percent of the total next year, at which point a multibillion-dollar IPO could be in the offing if AppNexus can sustain its torrid growth. A buyout by Yahoo, Microsoft or Facebook remains an option. No such talks have been in the works, O’Kelley says, though he promises such a sale would make Yahoo’s recent purchase of Tumblr for $1.1 billion look like small money. It would also make O’Kelley ad tech’s favourite son, suiting his ambition just fine. “It would suck if I was a guy who just had a great idea once,” O’Kelley says. “We are talking about leaving a real legacy here, not just on a small part of the industry, but on all the internet. We are what pays for the internet.”

First Published: Jul 24, 2013, 06:29

Subscribe Now