Hollywood mogul Barry Diller begins again

Most tech billionaires are precocious revolutionaries. Then there's Barry Diller. The former Hollywood mogul has ground his way to a $4.2 billion technology fortune, one unsexy spinoff at a time—and a

Alberto E. Rodriguez/WireImage via Getty Images

Oh no!” Barry Diller’s leathery voice booms when talk turns to paparazzi photos from a recent vacation on his $40 million superyacht. Resting on a curvy, arched sofa in his office, Diller, 77, has meandered from chatting about the champagne-fluteshaped floating island he’s building in the Hudson River to throwing barbs at Donald Trump to digressing into the French Revolution to describing IAC/InterActiveCorp, his evolving $20 billion internet assemblage. The pics in question documented a six-week summer yachting holiday in Europe on which Diller was accompanied by his fashion designer wife, Diane von Furstenberg, and a carousel of celebrity pals, from singer Katy Perry and actors Orlando Bloom and Bradley Cooper to Oprah and Jeff Bezos and his girlfriend, Lauren Sanchez.It’s the Friday after Labor Day, and Diller is still bronzed from his floating adventures, which took him from Stockholm to Scotland, then to France, and on to Italy, the Greek islands and Croatia. The paparazzi picked up Diller’s trail on the island of Panarea in Italy and again in Venice, where Bezos cuddled with Sanchez. “It’s embarrassing to me,” says Diller of the publicity.

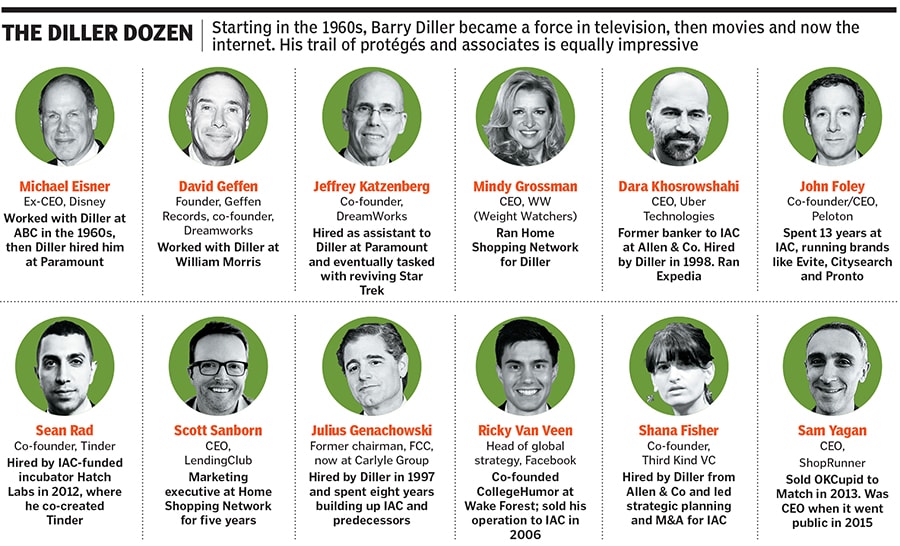

Over the past 55 years, as Diller’s swashbuckling career has taken him from deckhand to mutineer to admiral, he’s navigated upheavals in media and technology while at the same time making big bets ahead of (and sometimes counter to) almost every major trend. In a former life, he was one of the most powerful hired hands in Hollywood, heading Gulf & Western’s movie studio, Paramount Pictures, from 1974 to 1984 before leaving to build Rupert Murdoch’s Fox Broadcasting into the fourth national network. His string of blockbusters include Saturday Night Fever, Grease and Raiders of the Lost Ark at Paramount and The Simpsons at Fox. But in the 1990s Diller pivoted hard after a sojourn selling zirconium baubles on QVC convinced him that the future lay in the convergence of entertainment, commerce and the internet. Act Two (or Three or Four—who’s counting?) for Diller has been IAC/InterActiveCorp, an online conglomerate that has grown to a value of $20 billion after a ten-fold surge in its stock over the past decade, yielding Diller a $4.2 billion fortune.

“Barry’s had one of the most unusual careers of anybody in America,” says David Geffen, a close friend and former colleague, now worth $7.9 billion himself. “When he decided he was going to take over QVC I was shocked. I didn’t think that was good enough, or big enough, or important enough, or classy enough for Barry.”

In a 1993 New Yorker profile, Diller laid out a prescient vision of non-linear TV viewing habits, essentially describing Netflix. Yet when the time came to build his own streaming business, Diller admits, “the ideas we had were bad”. Despite owning Ask Jeeves and Vimeo, he was beaten by Google in search and YouTube in video. He passed on the chance to invest in Chinese internet giants like Baidu at their dawn and Amazon after the dotcom bust. When Priceline was offered to him, he was stretched thin because of trouble at Expedia and was unable to pounce.

But Diller’s hits have more than made up for his misses. At IAC he has built and spun off ten publicly traded companies, including Ticketmaster, travel giant Expedia and Match Group, Tinder’s parent company, worth a combined $70 billion (at an estimated cost of $12 billion).

“Seventy billion dollars from nothing is a lot, but it isn’t $700 billion,” Diller concedes. “It would be so absurd and almost revolting for me to feel bad about that disparity. I wasn’t a founder of a single company. We were opportunists and I think pretty good managers. I wish I had invented a single company, but I also wish I could dance like Fred Astaire and sing like Adele.”

Since he took control of IAC’s predecessor in 1995, he’s produced 14 percent compound annual returns for shareholders, outperforming Berkshire Hathaway and trouncing both the S&P and Hollywood giants like Disney, CBS and Viacom. “He understood the dynamics of the digital world early among the media moguls, and he captured it,” says billionaire Mario Gabelli, an IAC investor. “Barry always has a plan,” Geffen adds. “I’ve never seen him be anything but successful. To bet against him would be a fool’s errand.”

Now Diller is again challenging convention. He is preparing to spin off the remainder of Match Group, IAC’s crown jewel, and the handyman marketplace ANGI HomeServices, worth a combined $20 billion. Then Diller will start again with a hodgepodge of internet unknowns and has-beens. “All of our transmutations have been about renewal,” he philosophises. “Spinning off Match is a process of renewal in that IAC the company gets to start inventing again. We are shrinking in order to grow again… shrinking with $5 billion or so of cash.”

Former Diller lieutenant Dara Khosrowshahi, now the CEO of Uber Technologies, says, “Barry’s like a shark. If he stops swimming, he dies. So he just keeps going.”

*****

To understand Diller, it’s important to realise that he relishes being an underdog. When it comes to acquisitions, he tends to buy misfits that others dismiss. That, in fact, is the plot of one of Diller’s earliest successes, the 1976 comedy The Bad News Bears, which Diller produced after taking over Paramount. In it, Walter Matthau plays a flamed-out ballplayer who transforms a talentless team of California Little Leaguers into contenders for the championship. It’s a perfect summary of Diller’s career.

“Everybody thought this television kid knew nothing about movies,” he says, noting that the $9 million film grossed $32 million. “I had this little movie, and I was able to mother it to completion. This little jewel wasn’t the biggest movie ever made, but it was a joy,” Diller says, beaming. “Everybody was betting against it.”

Born in San Francisco in 1942 and raised in Beverly Hills, where his father ran a successful real estate business, Diller attended UCLA but dropped out eventually finding a job in the mail room of the William Morris talent agency. There he worked alongside future industry icon David Geffen. He moved to ABC in 1964 and hit pay dirt a few years later, at the age of 25, birthing the network’s Movie of the Week concept, the start of a decades-long rise. At 30, he was named vice president of prime time a year later, in 1974, he decamped to the silver screen at Paramount, where he worked for almost a decade, producing a stream of hits like Raiders.In 1984, Diller left that cushy job to build a fourth national network for Rupert Murdoch. Onlookers predicted disaster. With little budget, he built Fox Broadcasting into a powerhouse by making contrarian bets on shows like Married... with Children and The Simpsons. Having conquered Hollywood, Diller decided to start over. “I was getting less and less curious, which, for me, is fatal.” He quit Fox in 1992 and wandered America with a Macintosh PowerBook, searching for his future.

Serendipity arrived when his friend and now wife of nearly two decades, von Furstenberg, began selling scarves on QVC. They sold like hotcakes and she tipped him to the opportunity. “I had only known screens for narrative storytelling purposes,” Diller says. “Here I saw a screen being used at this primitive convergence of telephones, televisions and computers.” He was hooked, thanks to von Furstenberg, who has an estimated net worth of $200 million. “I will say an idea, or she’ll say something, and it bounces, and the ball goes in the air and it drops where it drops,” Diller says of their relationship. “We are stimulants in each other’s lives.”

In 1992, QVC was put up for sale, and Diller says with the backing of Comcast’s Roberts family he invested $25 million and took control of the company. He tried to buy Paramount, but got in a bidding war with Viacom’s Sumner Redstone and lost the $9.6 billion prize. Then, in 1994, on the eve of a planned merger with CBS, the Roberts bought QVC out, earning Diller a $130 million windfall. But he was jobless once again.

Help came in the form of Liberty Media’s John Malone, who, Diller says, helped finance his acquisition of Silver King Broadcasting in 1995. At the time, Silver King was little more than a collection of UHF stations that controlled a stake in QVC’s competitor, the Home Shopping Network. But it was the beginning of IAC.

With Malone’s backing, Diller started making deals—and lots of money. In 1997 he cut a deal to buy 55 percent of cable-TV network USA from Edgar Bronfman Jr for $4.1 billion. Less than four years later he flipped it to Vivendi for $11 billion. In 1997 he also bought half of Ticketmaster for $210 million, snapping up the rest in 2003. He spun off Ticketmaster in 2008 and merged it with Live Nation two years later. The business, a near monopoly in concert and sports ticketing, is now worth $15 billion.

In the late 1990s, Alexander von Furstenberg, Diane’s son, recommended that Diller look into an early online dating site. Both believed dating would move online. They soon discovered Dallas-based Match.com and began investing in it in 1999. Eventually it would merge with hipper platforms like Tinder and Hinge. With a total investment of $1.6 billion, he’s seen the value of IAC’s stake grow to $17 billion. Travel, Diller also predicted, would move from agencies to the web. In 1999 he purchased Hotels.com for $245 million and then, in 2001, struck a deal with Microsoft to take control of Expedia for $1.5 billion, agreeing to complete the purchase just after the September 11 attacks. “If there is life, there’s travel,” Diller decided, persuading himself to complete the deal. Expedia is now worth $20 billion.

Not every deal has panned out. In 1999, Diller tried and failed to buy Lycos, an early search engine. That’s probably a good thing given that a small company named Google had been founded a year earlier. But he still managed to waste nearly $2 billion in search, buying the also-ran Ask Jeeves in 2005.

Jeffrey Katzenberg, who worked under Dillerat Paramount, believes Diller’s instincts and doggedness, learnt over two decades in Hollywood, have transferred perfectly to the web and IAC. A movie like The Bad News Bears, he points out, is willed into existence by a producer with conviction, the same way Diller has impelled some of his disparate web properties to success. “Barry would always say there’s no natural momentum to a movie,” Katzenberg says. “It must be driven by somebody’s belief and passion.”

*****

Diller’s current hand looks challenging. He’s slimming IAC down at a time when the behemoths of Silicon Valley look every bit as powerful as John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. As Diller entertained hours of questioning from Forbes in early September, Match shares were falling after Facebook said it would redouble its online dating efforts. Meanwhile, ANGI HomeServices, which grew out of Angie’s List, a decades-old directory of reliable local businesses, plunged 45 percent in August when its profits fell short.

There are also lawsuits. The co-founders of Tinder, Sean Rad and Justin Mateen, claim they were deprived of billions when the app was consolidated by Match. Diller responds sharply: “Sean Rad is a blowhard and a bad actor.”

Facebook, Diller adds, has yet to register as a threat to Match. “I’m not overly worried,” he quips, then brings up the possibility of regulation. “I think that there are real issues,” he says, turning his attention to Google. “It’s okay to take our money as advertisers. It’s not fine, in my opinion, to then try and get our customers.”

Diller has delegated much of IAC’s day-to-day to a new line of deal-hungry executives, led by Joey Levin, 40, a former M&A banker who took over as CEO in 2015. Levin spearheaded the $10 million acquisition of Bluecrew in March 2018. Bluecrew connects construction and logistics workers with jobs and fits in with IAC’s vision for the future of ANGI HomeServices. In a similar vein, last October, ANGI paid an estimated $150 million for Handy, an on-demand cleaning service, and a few months later Levin spent $250 million on Turo, an app that lets motorists share their idle cars like homeowners rent out Airbnb rooms.

Diller’s deals are puny compared with the ones cut in Silicon Valley, but they are much more likely to make money. The rival internet conglomerate SoftBank is sweating to salvage its massive investments in Uber ($7.4 billion) and We-Work ($10.6 billion). IAC is more old-school. Diller would rather invest years—and millions—growing a property like ANGI into a multibillion dollar business than try to jump-start the process with a bazillion-dollar investment.

Even the duds are put to work. IAC continues to own Ask Jeeves. Now rebranded as just Ask, it is split into a media company and web browser app. It still draws 120 million monthly users, and IAC milks it for cash. Diller’s eight-figure acquisition of Connected Ventures, owner of CollegeHumor, drew hackles in 2006. But Diller might have the last laugh. Tucked inside was a media player called Vimeo.

In 2015, Harvard MBA Anjali Sud, 32, pitched Levin and Diller on abandoning Vimeo’s money-losing original content in favour of doubling down on it as a publishing tool for filmakers. Much the way WordPress is the software behind hundreds of millions of blogs, Vimeo is now the publishing platform of choice for more than a million paying subscribers who generate more than $200 million in annual revenues. It’s gone from bad-news bear to IAC gem, growing at a 26 percent clip to an estimated $2 billion valuation.

In 2019, Diller’s IAC will generate $5 billion in revenues, up about 12 percent over last year. Its $20 billion market capitalisation, however, seems to reflect investments in only two operations, 81 percent of Match Group and 84 percent of ANGI HomeServices, both of which Diller is considering jettisoning.

But if you think that you’ve heard the last from Diller and his band of underdogs—from Investopedia and Ask to Bluecrew, Brides and Turo—you’re mistaken. “My heart has been in this little tiny company that has grown up,” says Diller, wistfully. “At some point, I said, If they don’t laugh at me, something’s wrong.”

First Published: Nov 19, 2019, 14:21

Subscribe Now