Harry Stine Is Revolutionising US Agriculture. Again

Harry Stine built an obscure $3 billion empire by breeding a better soya bean seed. Now the richest man in Iowa thinks he has revolutionised corn, the Earth's most popular crop

On one of the windiest days in recent memory Harry Stine, the richest man in Iowa, cranes his neck to examine the elevator shaft inside the 110-foot steel observation tower next to his garage. “The cables look awfully frayed. Who knows if it will last one more time?” he chuckles. Nonetheless, we hop into the elevator cab, he flips the switch to get it moving, and up we go as the wind rips into us at 40mph.

Stine, the 72-year-old founder and owner of Stine Seed, the largest private seed company in the world, built this tower back in 1987 so he could get a good view of his empire, some 15,000 acres of frozen Iowa farmland. Aside from a small, glass-walled house, it’s his only visible indulgence. Once home to his father’s hardscrabble cattle-and-crop farm, Stine has, without attracting any widespread notice, developed some of the most valuable agricultural products on Earth here. With more than 900 patents, Stine sells his coveted soya bean and corn seed genetics to agri-giants like Monsanto and Syngenta, nabbing estimated annual sales of more than $1 billion with margins in excess of 10 percent. Along with his four children, Stine owns almost 100 percent.

It is a good reminder to those tempted to confine “innovation” solely to the world of Silicon Valley that some of the most impressive and fundamentally important advances on Earth are occurring today in agriculture, and the global epicentre is America’s heartland. The seed market—a $44 billion worldwide industry that supplies crop growers with the essential element they use to plant, harvest and sustain the world’s food supply—is expected to double in the next five years as crops fortified with more resilient genetics improve yield and efficiency. That’s good news since the world’s population continues to grow by about 85 million every year, while arable land remains scarce.

With a combined market value of $320 billion, five publicly traded conglomerates own most of the action: Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta, Dow and Bayer. Then there’s Stine. Based in Adel, Iowa, the dozen or so companies under Stine’s umbrella form an unlikely titan at the heart of the market, directly or indirectly generating revenues from almost 50 million acres of crops in the US each year.

Stine Seed does business with all of the heavyweights and has for more than three decades, primarily because it has something everybody else needs: The best-performing soya bean seeds in the business. Through plant breeding, a roughly 10,000-year-old technique that’s not unlike creating Thoroughbred horses or show dogs, Stine has been perfecting the genetic makeup of soya bean seeds—primarily used in animal feed and to produce vegetable oils—since the 1960s. The basic technology may be ancient, but an innovative, data-savvy strategy, married with shrewd leadership and a classic midwestern work ethic, has made Stine’s operation best in class. He isn’t bashful about what his small-town company has accomplished. “Our germplasm—our genetic base here—is the best in the world,” says Stine. “We dominate genetics in the industry.”

Today 60 percent of all US soya bean acreage is planted using genetics developed by Stine’s companies, which also have a strong presence in South America and other international markets. Forbes estimates that Stine’s company—which, among other things, also breeds corn genetics, creates plant traits in its biotech lab and has a small but growing commercial seed sales operation—is worth nearly $3 billion.

While rivals scoff, he now thinks he can double the world’s output of corn, the most popular crop on Earth. By breeding corn seeds genetically predisposed to thrive when planted in high densities, he thinks he can supercharge the engine generating animal feed, biofuels and food for the whole planet. “We’re going to be able to double corn yields very easily,” says Stine. “And apparently a lot of people working in the same industry can’t see that.&thinsp… They think, ‘How can this be? And furthermore, how can this little farm kid out here be doing this?’&thinsp”

After seven years of genetic tinkering, he’s won plenty of converts. “It’s an insight that will revolutionise the corn industry,” says Dermot Hayes, a professor of agribusiness at Iowa State University. If it works out, it won’t be the first time this farm kid, unknown outside his industry, has changed the world.

A tall man partial to Levi’s and blue button-downs with pens in the pocket, Stine stands on the burnt-orange carpet in his office—a little-changed artefact of the Reagan era littered with the nuts, berries and, especially, mushrooms he likes to forage for (he has a handwritten log detailing when and where he’s found each of the 32,000 morel mushrooms he’s nabbed in recent years). He’s waving several reams of paper, filled with three years of yield results that drive Stine’s corn euphoria. At almost every location they plant them, he says, his seeds outperform any other variety.

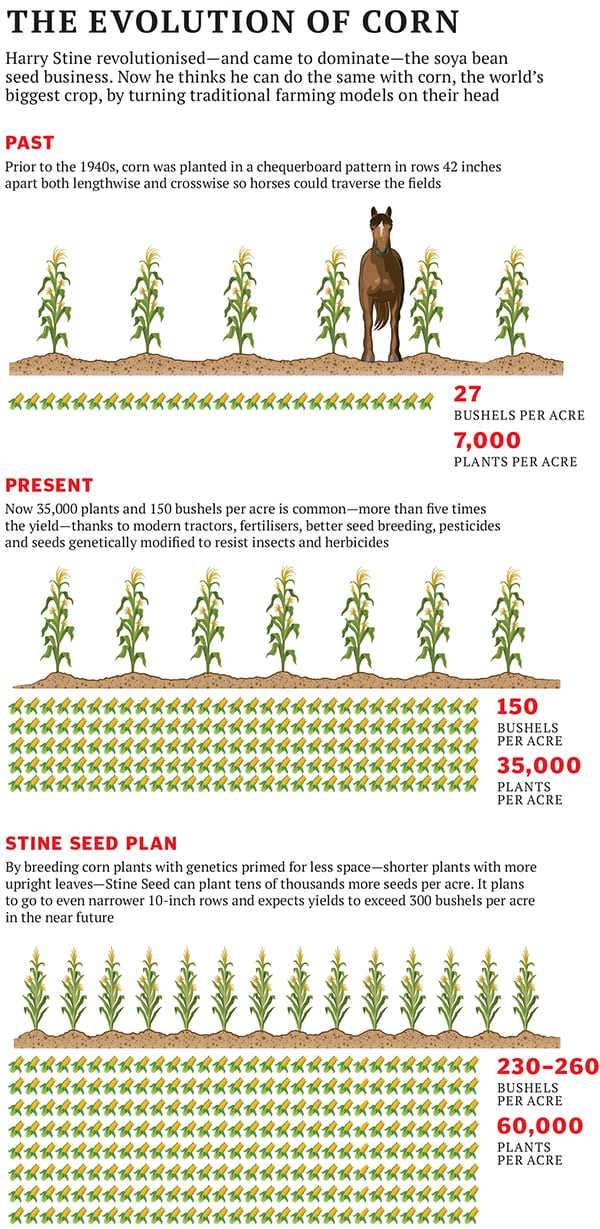

The secret to Stine’s golden corn? Efficiency. In the early 1930s, prior to the Dust Bowl, 7,000 corn plants per acre were grown in the US, yielding about 27 bushels per acre. Seeds were planted in rows 42 inches apart so horses could traverse the fields. Now 35,000 plants and 150 bushels per acre is common— nearly five times the yield—thanks to modern tractors, fertilisers, pesticides and seeds genetically modified to resist insects and herbicides. But while genetic modification—using biotechnology to insert a genetic trait into a seed— grabs headlines (and stokes health fears, despite overwhelming scientific evidence of safety), traditional breeding programmes by seed developers have done just as much to raise yields.

Stine noticed that corn plants hadn’t changed much in generations. Tall has always been sexy for corn, even though less than half of the plant is actually harvested. That means most of the biomass is using valuable resources that don’t necessarily improve a farmer’s yield. The conventional spacing of corn rows has also largely persisted at 30 inches or more in modern agriculture, with narrower rows in use on less than 5 percent of corn acres in North America as of 2012, according to rival DuPont Pioneer.

Stine flipped the conventional wisdom on its head. He began breeding corn to thrive at higher planting density: Shorter plants with smaller tassels and more upright leaves that attract more sunlight. A leaner, more efficient plant. After breeding many descendants of the seeds with that genetic makeup, the company has developed corn that can be planted in much narrower rows—12 inches or even pairs of rows 8 inches apart—increasing the number of plants per acre to as much as 80,000. And, of ultimate importance, substantially increasing a farmer’s harvest.

“Harry’s breeding for it,” says Van Wiebe, an agronomist with Hefty Seed in Buhl, Idaho, who has seen a 30 percent difference between Stine’s seed and those of his rivals in his experimental fields. “It’s going to be the way of the future.”

Not everyone buys what Stine is selling. A DuPont Pioneer study from 2012 concluded that for most of the Corn Belt, narrow rows do little to increase yields. “Future changes in production practices could favor narrow rows at some point,” says Mark Jeschke, DuPont Pioneer’s agronomy research manager. “But no research thus far has shown that ultrahigh populations combined with narrow rows significantly increased corn yield.”

“It is an interesting story and a great conversation piece,” adds Tony Vyn, professor of agronomy at Purdue University, “but a sideline to the real drivers of corn yield and economic efficiency gains that are needed most for this decade.”

For farmers, there’s a sizeable capital risk in switching. Buying more seeds per acre is expensive. It also requires more fertiliser and new planting and harvesting machinery specially fitted for the narrower rows. To pay for the change, you’d need at least an immediate 10 percent yield improvement—and 20 percent to 30 percent to really benefit a farm’s bottom line, estimates Bruce Rastetter, CEO of Summit Group, which grows corn and soya beans on 20,000 acres of land in Iowa and Nebraska. “It’s going to take some time,” says Rastetter, who is experimenting with Stine’s model.

“I don’t see extremely quick adoption, but I do think there’s an early-mover advantage to doing it and learning to do it well.”

Stine is hardly alone in his beliefs. Monsanto is doing similar work, and he’ll have to battle with it for market share should crop growers flock en masse to high-density planting. “We’ve worked a lot in that space but also in the design of the plants and equipment,” says Robert Fraley, Monsanto’s chief technology officer, who has been doing business with Stine since the early 1980s. With the world adding 800 million to 900 million bushels of corn demand each year, Fraley says corn seed still needs more innovation, and he buys into Stine’s vision: “We absolutely think it’s possible to double yields.”

We’re willing to give Stine the benefit of the doubt for a simple reason. He’s already revolutionised agriculture. Twice. In 1994, the US government granted its first patents on the full genetic makeup of a soya bean. Previously, only asexual plants like rosebushes or apple trees could be patented, not self-pollinating crops like corn and soya beans. Stine Seed was first in line to get its top-performing varieties patented. It wasn’t a coincidence: As early as the 1970s, Stine, who had taken one business law class at McPherson College, a small liberal arts school in Kansas, was stipulating in contracts the royalties companies had to pay for using his seed and prohibiting them from using the seeds their harvest produced to plant for next season. Crucially, it also forbade them from using his seeds to breed their own.

“His was the first company in the industry with soya beans to structure licensing agreements so that when companies took a contract with him they could not breed,” says Philippe Dumont, a lawyer and seed industry veteran who has spent the past decade working for Bayer. “It shows a superior foresight.”

It also helped secure Stine, in 1997, one of the most pivotal and lucrative deals in agricultural history. At the time, Monsanto—with Fraley, then president of the company’s genomics group, leading the charge—had developed the biotechnology to insert genes into crop seeds, making them resistant to glyphosate, the plant-killing herbicide in the company’s dominant weed killer, Roundup. For farmers the “Roundup Ready” soya bean seed would be an industry-changing innovation that reduced time and labour battling weeds. But a fancy biotech trait offered limited value if the genetic base of the seed was inferior and overall yields suffered. Roundup Ready technology combined with Stine’s industry-leading soya bean genetics was a natural fit.

When a battalion of Monsanto lawyers and dealmakers descended on Stine Seed to finalise the deal, they found Stine alone in the company’s conference room at a ping-pong table (Stine still rarely loses). “If you really want to be fair here, you need to go get two more [lawyers],” he smirked.

Neither party will disclose the agreement’s terms, but that deal contributed to the phenomenal success of the Roundup Ready soya bean seed, a technology that’s now used in 96 percentage of the soya bean acreage in the US, likely generating in excess of $10 billion for Monsanto since 1997. Stine will only say he receives a cut from his company’s contributions to Roundup Ready soya beans, and its relationship with Monsanto extends well into the future.

That lead was solidified in 2013, when the protections of patented seeds like Roundup Ready withstood a challenge in the Supreme Court in the United States. The case went in Monsanto’s favour, affirming intellectual property rights for plant genetics. Stine’s business model had been blessed by the highest court in the land.

Stine’s savvy is homegrown. After graduating from McPherson in 1963, he did two quarters of graduate work at Iowa State, then went home to work on his father’s modest farm. The family was poor and the work both long and hard—rising at 6 am and finishing at 6 pm was the norm, except in summer, when the hours were even longer.

After learning about some anomalous soya bean plants with extra seeds in a nearby field, Stine became obsessed with breeding higher-yielding seeds to boost profits. Even if the process has grown more involved and advanced, the strategy behind breeding has changed little in ten millennia. “It’s very simple. You take good parents, and you make lots of offspring,” says Stine, who learnt the basics in under an hour from an Iowa State technician. “It takes a minute and a half to learn what there is to learn about plant breeding.”

At the time public universities dominated breeding, and for good reason: Profits were limited, since intellectual property rights for soya bean plants didn’t exist—and wouldn’t for another 30 years. Additionally, it was a labour-intensive, painstaking endeavor, unsuitable to most businessmen or dawn-to-dusk farmers but perfect for Stine, innately curious and capable of intense focus, despite a childhood filled with academic struggles. He didn’t know it then—and wouldn’t for several more decades—but he suffered from dyslexia and also mild, high-functioning autism. Knowledge of those diagnoses was all but non-existent at the time. Back then, he says, he just thought he was “retarded”.

“I’m a data and information and facts person I’m not a people person. I don’t understand how people’s brains work and why they do what they do,” says Stine. But, as a consequence of his learning disabilities, Stine always worked slowly and carefully. He also possessed a canny, fluid mental aptitude for data and math. His “disabilities” were actually advantages that let him see things in ways others did not.

“Those qualities he has have enabled him to do in business what he has done. He has the right combination of everything,” says son Myron, who has worked alongside his father at the company for 20 years. “When you put him in the room with a bunch of people, he’s going to outpace everybody intellectually.”

Stine founded the first private soya bean research and development firm in the US in 1968. By the mid-1970s, under a new company called Midwest Oilseeds, Stine was operating the most widely used soya bean genetics company in the US, licensing the robust seeds it bred for royalties. Though the company also began breeding corn seed genetics, soya beans remained its most profitable niche.

It was around this time that Stine recognised the necessity of protecting his valuable genetics. If a farmer could buy your seed one year and then simply use the offspring or seeds from the plants it grew later, he could cut the seed developer out of the loop. Moreover, he could start his own breeding programme. The contracts Stine drew up prohibited this.

Some still infringed and faced legal confrontation if caught, but largely the strategy worked. The company expanded throughout the 1980s, gobbling up smaller seed companies and conducting soya bean research in other climates around the country. The breeding process grew more advanced and automated, and by the early 1990s the company was testing 150,000 soya bean varieties annually and producing the highest-yielding seed on the market. The Stine network of 1,700 dealers was selling Stine soya bean products in 15 states under 160 brands. By the time it got its 1994 patent Stine had become the largest private seed company in the country, the bulk of its revenues still coming from royalties from licensing its award-winning soya bean genetics.

“There’s always wrinkles in his science and negotiations that catch you off guard,” says Monsanto’s Fraley. “He’s not afraid to speak his mind. But at the very bottom of it all, he has made a huge difference in the industry and he’s done it in his very unique and special way.”

As we stand high atop his tower, the wind streaking into us, “unique and special” seems a vast understatement. “Now here’s what’s going to happen. I’ll sit here,” he says, perched on the top bar of the guardrail, unfazed by the steep plummet behind him or the violent gusts. “And you sit next to me. And then we’ll negotiate.”

He’s kidding, of course. It’s a long-running gag he’s played on acquaintances, business competitors and even his wife, Molly, who had suffered the misfortune of the elevator actually breaking and had to climb down the ladder—in heels.

But the joke, conducted amid full view of his empire, serves as a playful reminder: Harry Stine, the dyslexic farm boy turned cunning negotiator, data savant and agriculture visionary, is on top of the world.

First Published: May 06, 2014, 06:25

Subscribe Now