If you want to see what the natural gas revolution in America has wrought, there’s no better place than the Sabine Pass liqueï¬ed natural gas port in coastal Louisiana. There you can peer into ï¬ve massive storage tanks, each almost big enough to contain Madison Square Garden. Taken together, they can hold the liqueï¬ed equivalent of 17 billion cubic feet of natural gas—a quarter of what the United States uses in a day.

They’re empty.

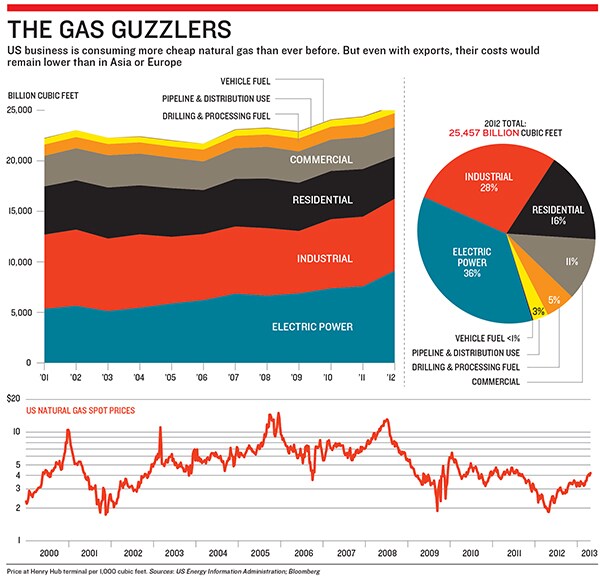

Built in 2008 by Houston-based Cheniere Energy when it appeared certain that the US would soon run short on natural gas and need imports to make ends meet, they ran headlong into the Great American Gas Boom. Drillers in recent years have unlocked so much gas from tight rock that America now enjoys record gas supplies and prices that are just one-quarter of what buyers in Europe and Asia pay. Projections are that the annual US gas supply could grow a further 25 percent by 2035.

Rather than let those tanks rust as relics, though, an army of construction workers is turning an import terminal into an export terminal. By 2016, a processing plant will be ready to ship out 500 million cubic feet of gas a day. In the three years after that, Cheniere expects to build ï¬ve more identical systems. The $12 billion investment should in turn be able to export about 4 percent of America’s current natural gas output, a remarkable turnaround for Cheniere and for Chief Executive Charif Souki. “It’s a revolutionary thing, absolutely astonishing, that America will be an exporter of hydrocarbons,” he says.

But just as astonishing as the idea of the US joining the likes of Qatar and Saudi Arabia are the hurdles this new push faces. In a remarkable oddity of 21st-century commerce, other companies—led by chemical giants from Dow and Huntsman to Alcoa and Nucor Steel—are ï¬ghting to block gas exports. Their self-interested argument: It’s against America’s economic interests to allow the cheap gas to flow outside its borders—and away from their hungry plants. “I’m not saying companies shouldn’t be able to export,” says Peter Huntsman, chief executive of Huntsman Corp. “But the question is, how much? Let’s not export an economic advantage that American consumers have today.”

In a bizarre coupling, the chemical companies have allied with environmentalists, including Congressman Ed Markey and Senator Ron Wyden. Markey has introduced two bills to block natural gas exports. One would prevent the Department of Energy, which uses ‘energy security’ as a ï¬lter on its approval process, from issuing permits.

All of which angers Souki, 60, a Lebanese-born former investment banker and son of a Newsweek correspondent. While he maintains that he’ll triumph over the odd consortium poised to stop him, he sees the effort as corporate welfare, masked under multiple politically expedient cloaks. “Unless we want to become the next USSR and have a centrally planned economy,” he says, “there is no debate and no choice.”

Shipping liquid natural gas is a tricky enterprise. Pipelines do the trick when you traverse a landmass. But while crude oil can be easily pumped out of the earth and dumped into a tanker ship, natural gas is generally too voluminous to be cost-effectively shipped via sea. The only way to solve this riddle is to chill the gas to –260o F, shrinking it into a concentrate 1/600 of its natural state—a process Souki’s plants are being built to accomplish.

A decade ago, natural gas prices were climbing and fears of scarcity had big oil and gas companies convinced that domestic supplies couldn’t keep up with demand. Souki, who had founded Cheniere as a small offshore exploration company, spent three years scouring the American coastline for viable spots to build a terminal. He settled on three sites in Louisiana and Texas, and made deals with landowners, addressed civic concerns and drew up plans for submission to state and federal agencies. Eventually he focussed entirely on Sabine Pass, situated just over the border from Texas. To help secure ï¬nancing, he convinced Chevron and Total to sign 20-year contracts for the option (but not the obligation) to import natural gas—for which the companies agreed to pay $250 million a year. It looked smart at the time in 2005, energy eggheads predicted that US gas imports would surpass 8 billion cubic feet per day by 2010, surpassing even Japan. Exxon Mobil and Qatar Petroleum started building their own import facility nearby, called Golden Pass.

Then came the fracking break-through, and hundreds of trillions of cubic feet of natural gas suddenly became accessible. Prices—$14 per thousand cubic feet in June 2008—hit $4 a year later. Despite the plunge, new gas supplies just kept coming. Great for American consumers—a Yale study estimates that Americans now pay $100 billion a year less for natural gas than at the peak—but horrible for Cheniere. “I built a $2 billion facility to import, and there were no imports,” says Souki. From $40 a share in late 2007, Cheniere stock slid to $1.12 in late 2008. It was only the payments from Chevron and Total that kept the company going.![mg_70201_gas_guzzler_280x210.jpg mg_70201_gas_guzzler_280x210.jpg]()

The glut was also great news for industrial companies, since natural gas is a key ingredient in all kinds of modern practices. For chemical ï¬rms like Dow and Huntsman, it serves as a feedstock for making ammonia, methanol, hydrogen and plastics. Dow announced a year ago it would spend $4 billion expanding in Texas. Shell Chemical announced a $3 billion plant in Pennsylvania to process ethane extracted from the gas. The American Chemistry Council added up $16 billion in chemical investments that would create some 17,000 new jobs and boost chemical output by $33 billion. Power utilities, steel manufacturers and other heavy manufacturers took advantage, too.

That tension surrounding the supply, and price, of natural gas created the ï¬reworks now exploding around Sabine Pass. Dow, Huntsman, aluminum giant Alcoa, steelmaker Nucor and other companies funded a slew of editorials and opinion pieces that said export efforts would undermine America’s “energy security”, stall a manufacturing renaissance and threaten the nation’s economic stability. “When natural gas is not exported or burnt for energy but instead used as an ingredient in manufacturing processes, it creates eight times more value across the economy and ï¬ve times the number of jobs in the supply chain,” Dow Chemical CEO Andrew Liveris said last year. The politicians began croaking in lockstep, especially given the opportunity to bash greedy oil and gas companies. And then came Markey’s bills, including the Keep American Natural Gas Here Act, which would force any company drilling for gas on federally owned lands to sell that gas only in the US, and the North American Natural Gas Security & Consumer Protection Act, which would have barred regulatory approval of any gas export facility until 2025. “This is America’s natural gas, and it should stay here in America,” Markey, the ranking member of the committee on natural resources, has said.

Neither bill will go anywhere. But they’re a window into the hurdles exporters will face. Cheniere’s Sabine Pass facility got its approval from the Department of Energy to export to any country two years ago. It is so far the only facility to be cleared to export to countries that do not have a Free Trade Agreement with the US. And getting a non-FTA permit is a make-it-or-break-it approval for these projects, because there’s only one big gas-importing country (South Korea) with a free trade deal with the US. Unless a facility can export to the likes of Japan, China and India, the economics likely won’t support a multibillion-dollar build-out.

The Energy Department has issued more than 20 export approvals to Free Trade countries (as required by law) but has been slow on non-FTA approvals, citing delays in studying whether approving more such exports would be in the public interest. In January, a group of senators introduced a bill that would speciï¬cally allow exports to NATO allies and Japan as well as any non-FTA country that the Administration wants to allow. But as it now stands, it will be at least the end of the decade before there are more than two operating plants exporting natural gas.

For the next few years, Souki’s perseverance will give him a near-monopoly. In 2009, faced with no business and few options, he refused to just mothball Sabine Pass. Instead, he started exploring the option of adding on far more complicated and expensive equipment to liquefy gas for export. His federal approvals to bring in foreign-sourced natural gas into Sabine Pass made it easier in 2011 to turn those permissions in the other direction.

Souki is no longer dependent on his legacy contracts for cash flow. Early last year, Blackstone plowed in a $1.5 billion equity investment another $500 million came from Temasek and RRJ Capital. Long-term contracts with BG Group, Total, Korea Gas, India’s GAIL, Spain’s Fenosa and the UK’s Centrica should translate into $2.6 billion a year in revenue when Sabine Pass opens in 2016. The stock has rebounded from $3 to $25—and Souki, who once had to borrow $30,000 to make payroll, has shares now worth $250 million.

But risk abounds. What if the massive gas projects being developed in Australia, Africa, Canada and Papua New Guinea glut the Asian market? What if China ramps up its own shale gas development? What if Russia lowers its European gas prices to recover lost market share? What if American gas prices go up? If the price differential between the US and the big foreign destinations shrinks to less than $6—the cost of liquefying plus shipping—then the incentive to export natural gas from America will vanish, and Sabine Pass will sit quiet.

This is why Souki can’t stand the complaining from the chemical company CEOs and the like. He’s taking a risk—why shouldn’t they? The only sure thing: Whether the US exports gas or not, American manufacturers will enjoy signiï¬cantly cheaper gas than the rest of the world for a long time to come—without Washington’s ï¬nger on the scales. “If it’s really their concern that it’s going to make their industries not competitive,” he says, “then I think they should shut down and do something else with their lives.”