Blowing up the venture capital model (again)

In just a decade, Andreessen Horowitz has backed a bevy of startup blockbusters—Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Airbnb, Lyft, Skype, Slack—and made just as many Silicon Valley enemies. To stay ahead, it

Marc Andreessen, co-founder and general partner of Andreessen Horowitz

Marc Andreessen, co-founder and general partner of Andreessen Horowitz

Image: David Maung/ Bloomberg Via Getty Images

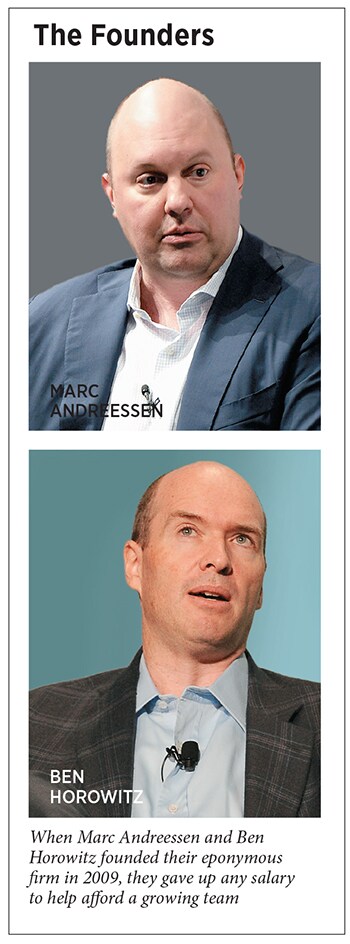

Emerging from the financial crisis in 2009, Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz laid out their campaign to take on Silicon Valley. The pitch deck for their first venture capital (VC) fund that year promised to find a new generation of “megalomaniacal” founders—ambitious, assertive, singularly focussed—who would, in the mould of CEO Steve Jobs, use technology to “put a dent in the universe”. In getting behind the likes of Facebook and Twitter, with a war chest that swelled into the billions, they proceeded to do exactly that.

Perched on a couch in his office at Andreessen Horowitz’s headquarters in Menlo Park, California, Andreessen, whose Netscape browser and subsequent company IPO were touchstone moments of the digital age, understands that the original word choice doesn’t land so well in 2019. His new take: “The 21st century is the century of disagreeableness,” he says. In an era of hyper-connectivity, social media and information overload, he says, those “disagreeables” will challenge the status quo and create billion-dollar companies. Ego is out, anger—or dissidence, at least—is in.

If that’s an equally unpleasant prospect, consider Andreessen, who’s 47, the perfect messenger. From showy cheque-writing to weaponising his popular blog and (before Trump) Twitter account to hiring an army of operational experts in a field built on low-key partnerships, he’s one of Silicon Valley’s poster boys for upending the rules. And it’s worked: In one decade, Andreessen Horowitz joined the elite VC gatekeepers of Silicon Valley while generating $10 billion-plus in estimated profits, at least on paper, to its investors. Over the next year or so, expect no less than five of its unicorns—Airbnb, Lyft, PagerDuty, Pinterest and Slack—to go public.

“What’s the number one form of differentiation in any industry? Being number one,” lectures Andreessen.

****

Staying number one, however, is even harder than getting there. Optimism that technology will transform the world for the better has soured with each successive Facebook data scandal (Andreessen, an early investor, still sits on Facebook’s board). Every revelation of social media’s tendency to foster society’s worst forces poses a challenge to his and his firm’s trademark techno-evangelism. And in the conference rooms of Sand Hill Road, stakes in the next Instagram, Twitter or Skype—three of its best-known early deals—are no longer the upstart VC firm’s for the taking. Today there are a record number of rival billion-dollar funds and a newer kid on the block in SoftBank, which, armed with a $100 billion megafund, makes them all—Andreessen Horowitz included—look quaint. And one thing about saying you’re going to fix a broken industry—you create plenty of competitors who won’t hesitate to capitalise on even a whiff of doubt that you can back up the hype with results.And so Andreessen and Horowitz, who rank 55th and 73rd, respectively, on this year’s Forbes Midas List, intend to be disagreeable themselves. They just finished raising a soon-to-be announced $2 billion fund (bringing total assets under management to nearly $10 billion) to write even bigger cheques for portfolio companies and unicorns the firm missed the first time. More aggressively, they tell Forbes that they are registering their entire firm—all 150 people—as financial advisors, renouncing Andreessen Horowitz’s status as a VC firm entirely.

Why? Well, VCs have long traded a lack of Wall Street-style oversight for the promise that they invest mainly in new shares of private companies. It was a tradeoff firms gladly made—until the age of crypto, a type of high-risk investment the SEC says requires more oversight. So be it, says Andreessen Horowitz. By renouncing its VC status, it’ll be able to go deeper on riskier bets: If the firm wants to put $1 billion into cryptocurrency or tokens, or buy unlimited shares in public companies or from other investors, it can. And in doing so, the thinking goes, it’ll again make other firms feel like they have one hand tied behind their back.

“What else are feathers for? They just like to get ruffled,” Andreessen says with a smirk. “The thing that stands out is the thing that’s different.”

****

From the beginning, Andreessen Horowitz had a simple credo: “We wanted to build the VC firm that we always wanted to take money from,” Horowitz says. Andreessen, whose Netscape breakthrough landed him on the cover of Time by the age of 24, didn’t need the fame. And neither needed the money. Colleagues at Netscape, they then co-founded a company that eventually became Opsware, run by Horowitz, who sold it to HP in 2007 for $1.7 billion.

Before founding their venture firm two years later, the pair dabbled in angel investing, where they gained a rebellious reputation, at least by the khakis-and-button-down standards of the Sand Hill Road crowd. Andreessen helped popularise startup advice through his “pmarca” blog, the spiritual predecessor of his Twitter stream, which became known for its surprise 140-character micro-essays on subjects from economic theory to net neutrality. (He’s widely credited with popularising the term “Tweetstorm”.) Horowitz, meanwhile, had a reputation for his ability to cite rap lyrics and his fandom for the relatively rough-and-tumble Oakland Raiders.

To build their VC firm, Andreessen and Horowitz modelled their brand strategy not on the industry’s elite but on Larry Ellison’s Oracle and its aggressive marketing during the enterprise software wars. They embraced the media, hosted star-studded events and badmouthed traditional VC to anyone who would listen. And while they started with small seed cheques to companies like Okta (now valued at $9 billion) and Slack ($7 billion), they ignored traditional wisdom and gobbled up shares of companies like Twitter and Facebook when those companies were already valued in the billions. For one investor in their funds, Princeton University’s chief investment officer Andrew Golden, it became a running joke how long it would take for other firms to complain about Andreessen Horowitz. “In the early days, it was within two minutes,” he says.

Buoyed by prior exits and some scrimping, Andreessen and Horowitz reinvested their money in the business, whose structure was modelled more on a Hollywood talent agency than a traditional VC firm. Neither drew a salary for years, and new general partners at the firm took lower salaries than is typical. Instead, much of its fees, the traditional 2 percent of funds managed that covers all of a firm’s expenses, went into a fast-growing services team, including experts in marketing, business development, finance and recruiting. Need to raise another funding round? Andreessen Horowitz specialists would give you “superpowers”, helping write your presentation, then coaching you through dozens of dry runs before scheduling the meets. Need a vice president of engineering? The firm’s talent team would identify and tap the best search firm, monitor its effectiveness and help choose the best candidate for the job. Human resources problem? Accounting crisis? “If something is going off the rails, you have the ‘Batphone’,” says Lea Endres, the CEO of NationBuilder, which makes software for non-profit and political campaigns.

And at the firm’s executive briefing centres, Andreessen Horowitz staff played matchmaker, enticing big corporations and government agencies with the prospect of seeing cutting-edge tech, then lining up relevant portfolio startups to present to the visitors. GitHub, the open-source-code repository the firm backed in 2012 before it was acquired by Microsoft for $7.5 billion, found the briefings so lucrative—good for $20 million in new recurring revenue in 2015 and 2016—that it posted a junior staffer to hang around the Andreessen Horowitz office full-time, its sales chief says. Consumer startups like the grocery delivery unicorn Instacart (a 2014 investment that now has a $7.9 billion valuation) scored partnerships with national retailers and food brands. On a recent visit in March, a dozen startups filed through one by one to meet with the Defence Innovation Unit, the branch of the Department of Defence that helps US armed forces find and pay for new technologies. The day before, it was Hachette Book Group. “We’ve had companies where it’s 40 percent to 60 percent of their pipeline, and I’m like, whoa, wait, we are not your sales force,” says Martin Casado, an enterprise-focussed general partner at the firm who sold his Andreessen Horowitz-backed startup, Nicira, for $1.3 billion.

The formula worked. The firm’s first and third flagship funds, $300 million and $900 million, respectively, are expected to return five times their money to investors, sources say. Its $650 million second fund and $1.7 billion fourth fund are expected to return three times their investment capital, good for the top quartile of firms, and are expected to climb. A $1.6 billion fifth fund, from 2016, is too young for estimated returns.

While they may be unwilling to credit Andreessen Horowitz publicly, other firms have clearly followed suit. From bloggers and podcast experts to resident finance officers and security experts, the number of non-investor professionals in the venture industry has swelled in recent years. “The idea of providing services, that feels like a table-stakes item now,” says Semil Shah, general partner at venture firm Haystack. “A lot of firms copied that.” At Okta, co-founder Frederic Kerrest says he’s routinely approached by other firms curious about building their own briefing centres to compete.

**** Image: Marc, Ben, Alex, Peter, Connie: Getty Images Photographs: Ethan Pines for Forbes[br]All this crowing and nose-thumbing has made enemies. Other investors never forgot how Andreessen Horowitz claimed the business was broken and it alone had the recipe to fix it. Almost from the beginning, gossip about the firm overpaying for deals was rampant, enough so that when Andreessen and Horowitz set out to raise their third main fund in 2012, the partners had to check every position with their portfolio companies so they could disprove the notion with their investors.

Image: Marc, Ben, Alex, Peter, Connie: Getty Images Photographs: Ethan Pines for Forbes[br]All this crowing and nose-thumbing has made enemies. Other investors never forgot how Andreessen Horowitz claimed the business was broken and it alone had the recipe to fix it. Almost from the beginning, gossip about the firm overpaying for deals was rampant, enough so that when Andreessen and Horowitz set out to raise their third main fund in 2012, the partners had to check every position with their portfolio companies so they could disprove the notion with their investors.

Meanwhile, their failed investments—and there have been high-profile ones, including Clinkle, Jawbone and Fab—and big missteps like Zenefits get magnified. Andreessen Horowitz’s well-publicised view, one it still holds, was that what matters is not how many companies you back that fail but how many become massive, outlier successes. Andreessen argues that only 15 deals per year generate all the returns, and he’s intent on seeing all the hot deals first.

Swinging for home runs magnifies whiffs, and Andreessen Horowitz blew the highest-profile Midas-list mover of recent years: Uber. The firm doesn’t admit to it now, but several sources with knowledge of the fundraising reveal just how close the firm was to getting a big stake—before letting it slip through its grasp. The until-now mostly untold story: In the fall of 2011, Uber’s co-founder Travis Kalanick was raising a red-hot Series B funding round and was keen to have Andreessen Horowitz lead. The firm, Andreessen in particular, was just as hungry to make it happen. By early October, Kalanick was calling other firms to tell them he had a handshake in place with Andreessen and another partner at a value somewhere around $300 million. At the 11th hour, however, the firm blinked. It would still invest, but with a structure that would value Uber at significantly less—$220 million, not counting the investment or an employee option pool, according to an email from Kalanick obtained by Forbes.

“They tried to surprise us,” Kalanick wrote to his investors. “So here we are. The next phase of Uber begins.” Kalanick instead turned to Menlo Ventures—which until then was being used as a stalking horse for leverage—and accepted its $290 million price pre-deal.

While Andreessen Horowitz backed Uber rival Lyft in 2013 and has already cashed out some of those shares at a profit, the firm wasn’t done with Uber. It participated in merger discussions between the two ride-hailing companies in 2014 and again in 2016, according to sources involved in the talks. If the deal had gone through, it would have given the firm a backdoor route to a piece of Uber. Either way, it’s hard to ignore Uber as the one that got away. The ride-hailing company, now valued at $76 billion, is getting ready for an IPO that could be four or fives times larger than Lyft’s. Andreessen Horowitz declined to comment on Uber.

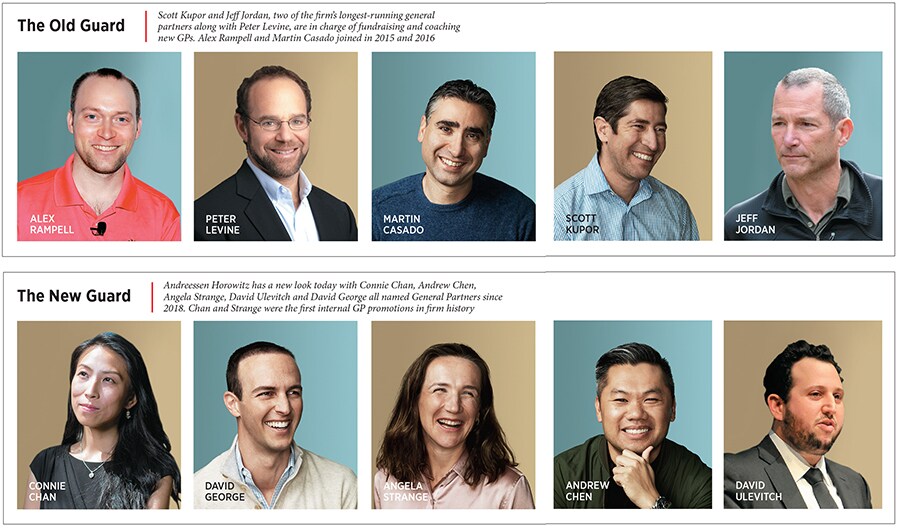

Andreessen Horowitz’s leadership has taken other raps. It was slow to diversify its management ranks—as recently as last year’s Midas List, all ten general partners (GP), the people who actually control investments and write cheques, were men—in part because it had a rule that GPs were required to be ex-startup founders and couldn’t rise up from the inside. In the past year they’ve added three women GPs but not before bleeding top talent.

Andreessen himself was caught on the wrong side of a fast-changing cultural climate in Silicon Valley in the months leading up to the election of Donald Trump in 2016, responding chummily by tweet to the now-banned far-right troll Milo Yiannopoulos, and seeming to joke, after India refused a new Facebook service, that the country might have fared better under colonial rule—earning a rare scolding from Mark Zuckerberg. In response, Andreessen became a digital recluse, deleting most of his past tweets. Andreessen says the purge wasn’t due to the backlash against his Facebook positions, though “that didn’t help” rather, he blames “the general climate”, specifically in politics and culture.

Both Andreessen and Horowitz have quieted down their bluster in recent years. Andreessen admits that, contrary to what they maintained when they were Young Turks, “VC wasn’t an industry in crisis”, but says it doesn’t matter how the firm got to its top-tier position. Horowitz goes further. “I kind of regret it, because I feel like I hurt people’s feelings who were perfectly good businesses,” he says. “I went too far.” As for the firm’s hiring rules, which contributed to its failure to add a woman GP, he admits it was hard for him to change something that had been such a core part of the firm’s outward-facing identity. “It’s a kind of a big thing for especially me to eat crow on,” he says. “It took probably longer than it should’ve to change it, but we changed it.”

****

Earlier this spring, a small group of Andreessen Horowitz executives gathers for a pitch meeting with a pair of founders from a low-profile but in-demand biotech company. The twist: The VCs are pitching the entrepreneurs, with operating team leaders advertising their own services to the startup, a health diagnostics company still in stealth mode. The entrepreneurs appear sceptical. When they met Andreessen Horowitz two years ago, after it wrote a small cheque in their seed round, the firm didn’t have much to offer bio startups. So for the next hour, they’re treated to example after example of how Andreessen Horowitz has added dedicated experts and connections to companies like UnitedHealth and Kaiser Permanente over the past 18 months. “We’ve found that a biotech company in Silicon Valley is really different from building just a tech company,” Shannon Schiltz, the firm’s technical talent chief, says.

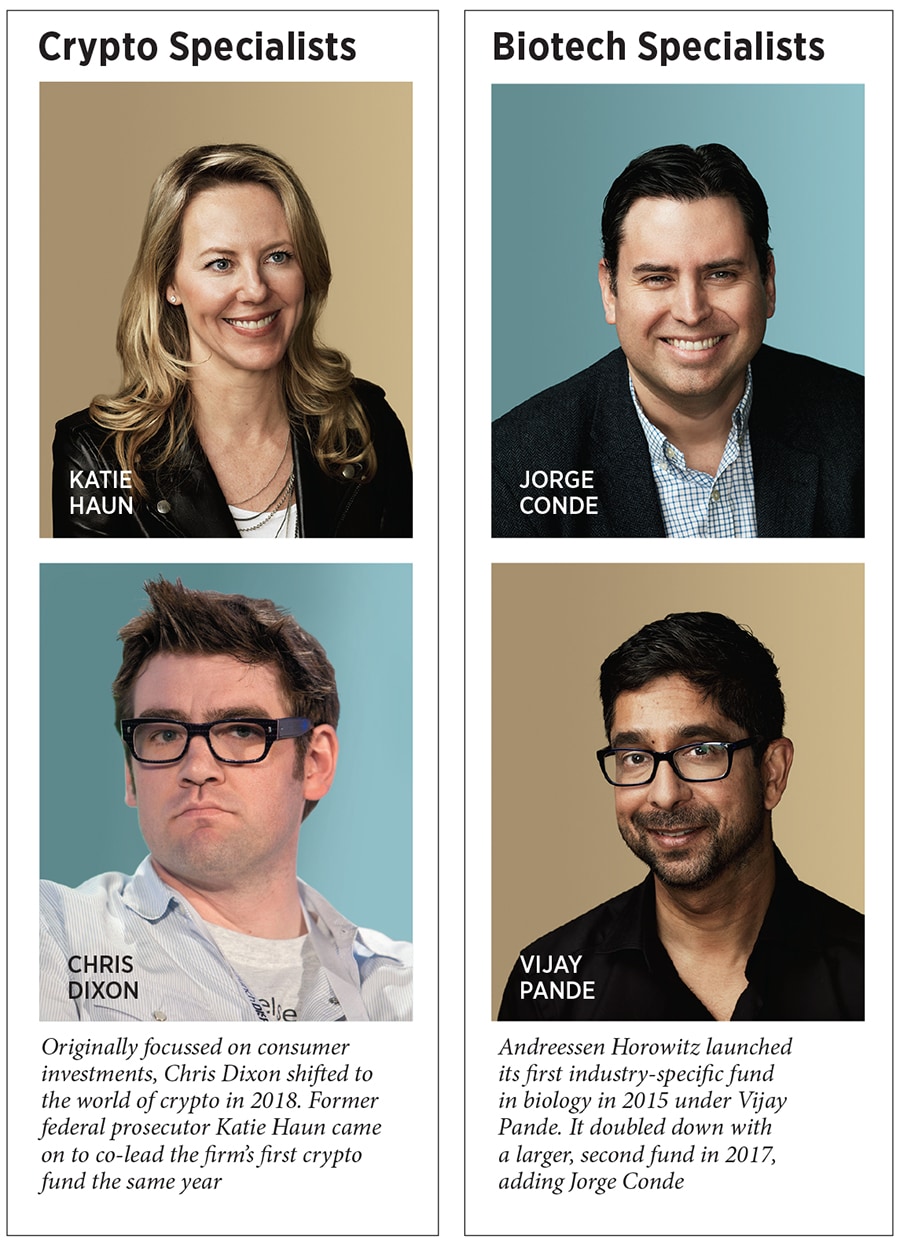

This reverse pitch is emblematic of the new-version Andreessen Horowitz. Besides turning the typical VC process on its head, the firm is investing in biotech, which it once said it would never touch. But scale and the pursuit of challengers to the status quo means pushing into new areas, and the firm has raised $650 million across two funds for the sector. “The brand doesn’t carry the weight in bio that it does in the tech community yet,” says Jorge Conde, a GP since 2017. “But we’ve made a concerted effort and planted the flag.” Specialists like Conde, who led strategy for Syros, a public genetics company, and co-founded a genome startup, are now the norm. Partners meet in committees by topic three times a week to evaluate deals, then convene as one firm on Mondays and Fridays to review likely investments. Images: Jeff, David, Chris: Getty Images[br]Which brings us to crypto. Last year the firm raised a $350 million fund in the up-and-down area. But until recently partners Chris Dixon and Katie Haun would meet in private with Horowitz, their fund technically a separate legal entity from the rest of the firm. That meant they had different email addresses and their own website, because of legal constraints on funds that register as traditional VCs. While Andreessen Horowitz was an early investor in crypto marketplace Coinbase and was one of many firms to catch cryptocurrency fever in 2017, it’s one of the few that doubled down even after the price of bitcoin and ether flatlined. SEC regulations consider such investments “high risk” and limit these stakes, as well as secondary purchases and fund or token investments, to no more than 20 percent of a traditional VC fund.

Images: Jeff, David, Chris: Getty Images[br]Which brings us to crypto. Last year the firm raised a $350 million fund in the up-and-down area. But until recently partners Chris Dixon and Katie Haun would meet in private with Horowitz, their fund technically a separate legal entity from the rest of the firm. That meant they had different email addresses and their own website, because of legal constraints on funds that register as traditional VCs. While Andreessen Horowitz was an early investor in crypto marketplace Coinbase and was one of many firms to catch cryptocurrency fever in 2017, it’s one of the few that doubled down even after the price of bitcoin and ether flatlined. SEC regulations consider such investments “high risk” and limit these stakes, as well as secondary purchases and fund or token investments, to no more than 20 percent of a traditional VC fund.

So Andreessen Horowitz spent the spring embarking on one of its more disagreeable moves so far: The firm renounced its VC exemptions and registered as a financial advisor, with paperwork completed in March. It’s a costly, painful move that requires hiring compliance officers, audits for each employee and a ban on its investors talking up the portfolio or fund performance in public—even on its own podcast. The benefit: The firm’s partners can share deals freely again, with a real estate expert tag-teaming a deal with a crypto expert on, say, a blockchain startup for home buying, Haun says.

And it’ll come in handy when the firm announces a new growth fund that will add a fresh $2 billion to $2.5 billion for its newest partner, David George, to invest across the portfolio and in other larger, high-growth companies. Under the new rules, that fund will be able to buy up shares from founders and early investors—or trade public stocks. Along with a fund announced last year that connects African-American leaders to startups, the new growth fund will give Andreessen Horowitz four specialised funds, with more potentially to follow.

That’s how the firm plans to keep up in a crowded VC landscape that experts say is bifurcating between specialist seed funds and a handful of giant, all-purpose firms. Traditional firms face more pressure than ever from the top and bottom of the funnel because of more sophisticated angel investor groups and non-VC giants like SoftBank’s Vision Fund, says Ilya Strebulaev, a Stanford professor who studies the industry. “VC is in flux,” he says. “We should expect a lot of fundamental changes.”

Some are inevitable, like the industry’s wising up to the Andreessen Horowitz playbook of using services as a deal sweetener. Or the inherent limits to the Andreessen Horowitz model, which will always require large and growing funds to cover expenses. Others are fixable, like mixed report cards from former operating employees. High pay isn’t enough for ambitious, younger staff to stick around long when there’s little chance of upward mobility, they say. And with veterans of Andreessen and Horowitz’s old company, Opsware, still spread throughout the firm, the sense that some employees get special treatment—and are immune to sanction—can sap morale. Meanwhile, the firm’s insistence on calling everyone a partner might seem harmless, or an annoyance for others. But if those titles are limiting the prospects of promotion and career growth, as one former partner notes, they may need to be retired like the firm’s old GP rule.

Most risky: Being the best-known VC firm on the block, or the one competitors mock until they copy, won’t matter if sweeping changes come for the entire industry. The world continues to wake up to the degree of power and influence big tech companies like Facebook and Google have over society—from livestreaming video of the Christchurch, New Zealand, mass shooter to YouTube videos that have united far-flung white nationalists—and to the likelihood they haven’t fully owned up to their responsibilities. Against such changing tides, the historical VC narrative of hypergrowth and Zuckerberg-like ambitions may fall flat.

In a choice that could be equal parts intransigence or naiveté, Andreessen invokes Facebook’s CEO as precisely the example of the kind of disagreeable founder who has the resolve to take the necessary, wrenching steps to make things right. “He just put out this memo talking about basically reinventing Facebook around privacy and messaging,” Andreessen says in March. “Just close your eyes and imagine a classic guy in a suit doing that.”

And though Andreessen says he’s too busy running the firm to have any hobbies—he’s reminded he has a young son now, too—he gives his own, grander twist to a quote from one of his favourite new TV shows, HBO’s Succession, to describe the mindset necessary to pull it off: “If you can’t ride two elephants at the same time, what are you doing at the circus?”

For the full list, click here: https://www.forbes.com/midas/#78ab1d815650

First Published: May 07, 2019, 14:27

Subscribe Now