On March 18, 2013, the government dropped a bombshell on Coinbase, a two-man San Francisco startup that had attracted 30,000 users to its cloud-based ‘wallet’ service for buying, storing and spending bitcoins.

That day, the US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) released “interpretive guidance" stating that those administering or exchanging virtual currencies such as bitcoin should be considered “money transmitters", subject to state licencing, federal registration and Bank Secrecy Act rules designed to help the feds uncover money laundering, tax fraud and other crimes.

Coinbase President Fred Ehrsam called the company’s lawyer. “He said, ‘It’s [only] guidance, and you guys are small, and it’s going to be a pain in the butt to comply. It’s going to take a lot of your time and money to do it’," Ehrsam recalls. “So his advice to me was to try to make a good argument as to why it [registration] didn’t apply to us and avoid it for the time being."

But that night, Ehrsam and Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong had a come-to-Jesus discussion. They agreed that skirting registration was wrong for their brand. While beloved by tech-savvy libertarians, bitcoin had taken a hit to its reputation after being sullied by hacks, Ponzi schemes and its use on the Silk Road dark-net drug market. Coinbase wanted to be seen as the easy, safe and legitimate way for a wider population to use cryptocurrency.

That week, the pair fired their lawyer and hired a new one. They had been operating with $600,000 from angel investors and were trying to raise Series A funding. The decision to register would add millions to Coinbase’s costs but also give it a strong selling point. At that time, the most well-known venture capitalist (VC) who had publicly expressed interest in bitcoin was Union Square Ventures (USV)partner Fred Wilson. When Ehrsam and Armstrong pitched USV, Wilson grilled them on their approach to regulation. Their compliant stance helped win them a deal.

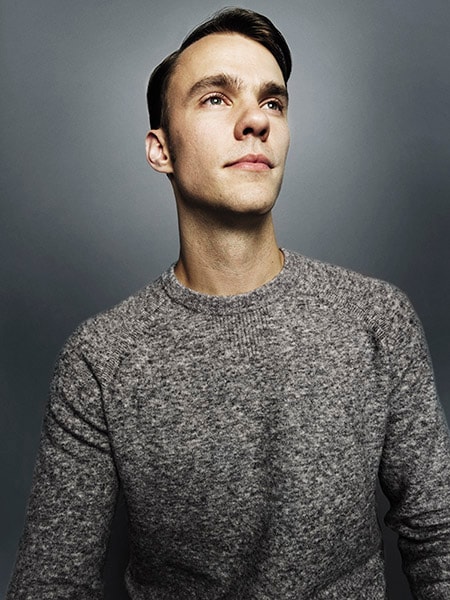

In May 2013, USV led a $6.1 million Series A fundraising for Coinbase. In November, the company got insurance (brokered by Aon) covering thefts and hacks. In December, Andreessen Horowitz led a $25 million Series B round for it, the largest VC investment in a bitcoin firm to that date. ![mg_92493_fred_ehrsam_280x210.jpg mg_92493_fred_ehrsam_280x210.jpg]() From the start, Coinbase president Fred Ehrsam have aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments

From the start, Coinbase president Fred Ehrsam have aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments

Image: Christian peacock

Today, Armstrong, 33, and Ehrsam, 28, have 117 employees and are pillars of the cryptocurrency establishment. Coinbase’s wallet is used by 4.8 million customers from 33 countries to buy, store and spend bitcoin and a newer cryptocurrency, ether. Customers link their wallets to their regular bank accounts and pay Coinbase a commission—1.49 percent for US account holders—to convert from or back to a government-issued currency.

A newer Coinbase business, the Global Digital Asset Exchange (GDAX), enables residents of 47 US states, Canada, the UK, the euro zone, Singapore and Australia to trade the currencies directly, either by manually clicking buy and sell buttons or by creating bots for algorithmic trading.

Coinbase stores about 6 percent of the world’s bitcoins, or some $700 million, on its computers. It gives customers the option of holding the only encryption keys to access their money or sharing the keys with Coinbase.

Investors have poured $117 million into building Coinbase’s infrastructure and controls. In January 2015, Draper Fisher Jurvetson led a $75 million round that included investors such as the New York Stock Exchange, the insurer USAA and the Spanish banking group BBVA, among others. Coinbase’s most recent funding, $10.5 million in July, valued the enterprise at $500 million and drew money from Japan’s largest bank, Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, ahead of Coinbase’s expected expansion into Japan in 2017.

Coinbase is now part of the establishment, and a strict enforcer of Bank Secrecy Act rules, in an industry fuelled by those who value bitcoin as a way to protect privacy or thumb their nose at government. If it sees suspicious transactions in a wallet, it may demand that a user explain himself, or it may suspend or close the account.

No surprise that a chorus of Reddit users have accused it of acting like “Big Brother", “spying for the US government" and using “Gestapo" tactics.

![mg_92487_bitcoins_280x210.jpg mg_92487_bitcoins_280x210.jpg]()

Cryptocurrency hasn’t made inroads at the speed Armstrong and Ehrsam anticipated, but they see it spreading beyond payments to, for example, new ways to crowdfund peer-to-peer networks that do file storage or predict events like the outcome of the World Series.

Raised in San Jose, California, by a father who was an environmental engineer for the Lawrence Livermore National Lab and a mother who taught math before going to work at IBM, Armstrong was the family entrepreneur. In high school, he built websites in a garage. As a Rice University economics and computer science double major, he launched a successful tutor-matching service, UniversityTutor.com, and learnt how difficult it was to take—and make—payments online.

After earning a master’s in computer science, Armstrong tried consulting and then lived in Argentina for a while before taking a job as a software engineer at Airbnb in San Francisco. That gave him a close-up view of problems connected with international money transfers, including delays, high (and opaque) fees and fraud. “If we sent $100 to Uruguay, we didn’t know how much they were going to get, and the company providing the service couldn’t even tell us," he recalls.

So when Armstrong stumbled upon the white paper by the (still anonymous) inventor of bitcoin, describing the currency and the novel blockchain protocol underpinning it, he was enthralled. Blockchain transactions are recorded on a single unified ledger, with copies of that ledger maintained by computers around the world—a revolutionary idea that drastically reduces transaction settlement time and costs, while improving security.

Ehrsam, too, had seen how financial middlemen could make steep profits. His first job out of Duke, where like Armstrong he had double-majored in economics and computer science, was as a foreign exchange trader for Goldman Sachs in New York. While growing up in Concord, Massachusetts, his passion was gaming. During high school, he went semi-professional, playing on two championship America’s Army teams. But he also spent lots of time talking business with his father, a Bain consultant with a Harvard MBA.

While at Goldman, Ehrsam became fascinated with bitcoin. He even made a little profit trading it at night using what he calls “superbasic" techniques, like going long when the term “bitcoin" was trending on Google. He quit Goldman after two years and moved to Sunnyvale, California, to work with Duke buddies on ideas for new apps.

![mg_92485_bitcoin_280x210.jpg mg_92485_bitcoin_280x210.jpg]()

In October 2012, he came across a post by Armstrong on Reddit describing his prototype for a cloud-based bitcoin wallet serving folks who weren’t “ubernerds" or didn’t want to risk storing it on their own computers. He emailed Armstrong, who had developed the wallet as a member of the June 2012 Y Combinator incubator class. They met and clicked: Ehrsam’s big-picture analysis complemented Armstrong’s coder’s focus. Armstrong invited Ehrsam to join him as Coinbase’s co-founder.

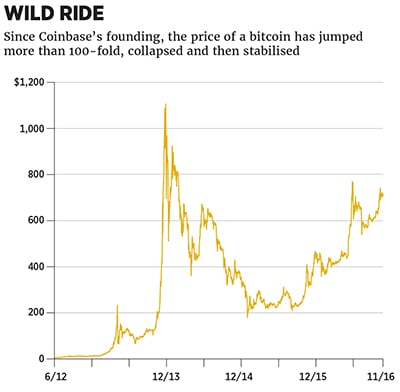

Since teaming up, they’ve seen plenty of high drama in cryptocurrency. There was the epic speculative bubble, as the price of a bitcoin rose more than a hundred-fold, from under $10 to above $1,100 in 2013, before sinking below $200 in January 2015. (It recently traded around $740, giving all the bitcoins outstanding a market value of $11.8 billion.) And there were those hacks—most notably of the Tokyo-based Mt Gox exchange, which shut down in 2014 after losing over $450 million of its customers’ funds.

Early on, the duo thought simplifying purchase transactions might speed bitcoin’s acceptance. In November 2013, they brought on Adam White, another bitcoin obsessive, and gave him an ambitious goal: Over the next year, sign up ten companies with more than $1 billion in sales each to accept bitcoins. White, now 33, was no slacker. After studying optical engineering, he served for five years in the US Air Force, then earned an MBA at Harvard.

White moved fast: Within two months, he had signed Overstock.com. Then, ten days later, the first Overstock bitcoin purchase was made—a $2,700 patio set. “That really opened the floodgates," White says. Other big names, including Expedia and Dell, followed, adding to bitcoin’s and Coinbase’s credibility. Today more than 45,000 mostly small merchants accept bitcoin payments through Coinbase—a number boosted by the fact that they get the first $1 million in transactions processed free.

After the run-up in bitcoin’s price, Coinbase noticed that a growing number of its wallet users were not buying patio furniture but instead were holding bitcoins as a speculative investment. With their customers hoarding, Coinbase had to purchase more bitcoins on exchanges. That made Armstrong nervous.

So in January 2015, Coinbase launched its own exchange, now called GDAX, which charges traders up to 0.25 percent for each transaction. The budding marketplace did $1 billion in trades in its first year, and given that a rival exchange, Hong Kong’s Bitfinex, was recently hacked to the tune of $72 million, Ehrsam and Armstrong’s “white hat" platform couldn’t be better positioned.

Despite GDAX’s success, Coinbase believes trading isn’t by itself the path to the widespread adoption of bitcoin. Ehrsam describes a lull in 2015 when the bitcoin apps that seemed most promising didn’t take off. Some other blockchain startups turned their attention toward the inefficiencies inherent in the back offices of financial firms. For example, Chain (like Coinbase, a member of the 2016 Forbes Fintech 50 listing of the most innovative financial startups) teamed with Nasdaq to build a blockchain-based system for trading private company shares and is working with Visa on a proprietary international business payments system.

Coinbase’s investors asked Armstrong and Ehrsam whether building private blockchains for financial firms shouldn’t be their next move. They rejected the detour, convinced that public blockchains and cryptocurrencies would produce greater innovation. “We have a high conviction that the open networks will be the ultimate winners even if there’s a lot of hype and cash being thrown around these closed blockchains," Ehrsam says.

Perhaps the most exciting development in cryptocurrencies is the emergence of more technologically advanced blockchains that can be used for more than simple purchases or money transfers. The most promising so far is Ethereum, which is designed to work in applications that incorporate “smart contracts"—when you execute a transaction, you’re agreeing to certain publicly visible contractual terms that have been built into the software. Thus developers can create markets that store registries of debts or promises and potentially move values around according to specific and sometimes complex instructions baked into the software/platform. Examples might be the assets due in a will or a futures contract. The key, of course, is the elimination of fee-greedy middlemen and counterparty risk.

In May, when Coinbase started allowing the trading of ether (the Ethereum coin) on GDAX, Ehrsam described its potential in a blog post this way: “Ethereum has taken what was a four-function calculator of a programming language in Bitcoin and turned it into a full-fledged computer."

The Ethereum blockchain has spurred the development of “app-coins" or “tokens" to crowdfund new businesses and operate peer-to-peer networks. One example is Augur, which in 2015 sold $5.3 million of Ethereum-based Reputation tokens that allow holders to share in the fees the site generates. Augur takes the “wisdom of the crowd" principle and lets participants create betting markets around the outcome of future events. Participants earn Rep tokens by reporting accurately on event outcomes but lose coins if their reports are inaccurate.

Another app-coin in development is Filecoin, which aims to fund and power a decentralised, peer-to-peer file-storage and file-sharing service that could compete with Amazon Web Services. Filecoins will be paid to those who host storage space, while those uploading files to the network will pay for storage with Filecoins. With such app-coins, entrepreneurs and developers can dream up new networks.

In May, The DAO (for “decentralised autonomous organisation") collected $150 million worth of ether from 10,000 people for a VC fund participants would vote on investments, with their votes weighted to reflect how many DAO tokens (built atop ether) they had purchased. But less than a month after it launched, someone exploited a loophole in The DAO’s code to divert $50 million worth of ether from investors’ accounts.

While such blowups are likely to slow the advance of cryptofinance, they also play into Coinbase’s competitive advantage—its internal controls and a cautious, patient culture reinforced by its heavyweight investors. Unlike some other exchanges, GDAX refused to trade The DAO tokens. Ultimately Coinbase’s success may hinge on its ability to be perceived as a champion for the liberating and innovative aspects of blockchain, while staying on the “right" side of the law. It won’t be easy.

In November, the Internal Revenue Service asked a federal judge to approve a sweeping “John Doe" summons requiring Coinbase to turn over the identities and transactions of all customers with a US connection who were active in 2013 through 2015. Juan Suarez, Coinbase’s lawyer, said while the company is “committed to cooperating with law enforcement in general", it feels “compelled to really resist" such a broad “fishing expedition." Stay tuned.

From the start, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong has aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments

From the start, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong has aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments  From the start, Coinbase president Fred Ehrsam have aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments

From the start, Coinbase president Fred Ehrsam have aimed to disrupt the financial industry and its profits, not governments