AT&T's Life After iPhone

After a half-decade being carried on Steve Jobs’ back, AT&T is reaching for a new strategy. CEO Randall Stephenson boils down his thinking to two words: Mobilise everything

Steve Jobs needed some advice. It was 2006, and Apple was working on the design for its first smartphone. Jobs had questions about its radio. He called up Ralph de la Vega, Cingular Wireless’ chief operating officer, who had helped broker the exclusive deal between Jobs and the telco, soon to be part of AT&T Inc, to carry the phone.

“‘How do you make this device be a really good phone?’” de la Vega recalls Jobs asking. “‘I’m not talking about how to build a keyboard and things like that. But I’m saying the innards of a radio that worked well.’”

AT&T had a 1,000-page manual that detailed how suppliers should build a mobile radio optimised for its network. “He said, ‘Well, send it to me.’ So I sent him an email. Thirty seconds, he calls me back. ‘Hey, what the … ? What’s going on? You’re sending me this big document, and the first 100 pages have to do with the standard keyboard’,” de la Vega says, laughing. “‘Sorry we didn’t take those first 100 pages out, Steve. Forget those 100 pages. Those don’t apply to you.’ He says, ‘Okay’, and he hangs up the phone.”

News quickly spread inside Cingular that Apple didn’t have to adhere to the specs, an act deemed blasphemous by the carrier’s CTO [chief technology officer]. De la Vega had signed a non-disclosure agreement in Jobs’ office that was so secretive it prevented him from describing the device to his bosses except in the most general terms. Board members didn’t even get to see one until after the deal was signed. “I said, ‘Trust me, this phone doesn’t need the first hundred pages.’”

Trust was a big part of the story behind AT&T’s deal with Apple. The country’s biggest phone company was a sclerotic mess of assets. Its shrinking landline business produced the majority of revenue. Its play on the future was a glitchy, hodgepodge cellular network cobbled from deals past.

It couldn’t pass up, as Verizon reportedly did, the chance to usher in the smartphone era with the man who had reinvented the computer and the music industry. “I told people you weren’t betting on a device. You were betting on Steve Jobs,” says AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson, talking candidly about the effect of the iPhone deal.

That one little phone transformed the whole company. AT&T still lags Verizon on many fronts, but since the iPhone deal, Ma Bell moves faster, embraces new technologies and partnerships big and small, and has decided to spend big—really, really big—to stay atop the data deluge. Since 2007, traffic on its network has doubled each year, and AT&T has spent more than $115 billion acquiring spectrum and building its network. The iPhone deal, says Stephenson, “changed everything. It changed our capital allocation. It changed how we thought about spectrum. It changed how we thought about engineering and designing networks. Suddenly, you go from thinking that 40,000 cell sites are sufficient to thinking it’s going to have to be multiples of that.”

The fruits of its spending are still on the come: Although AT&T’s new 4G network had the fewest complaints in a December Consumer Reports survey, it ranked last overall among the four big US carriers for the third year in a row.

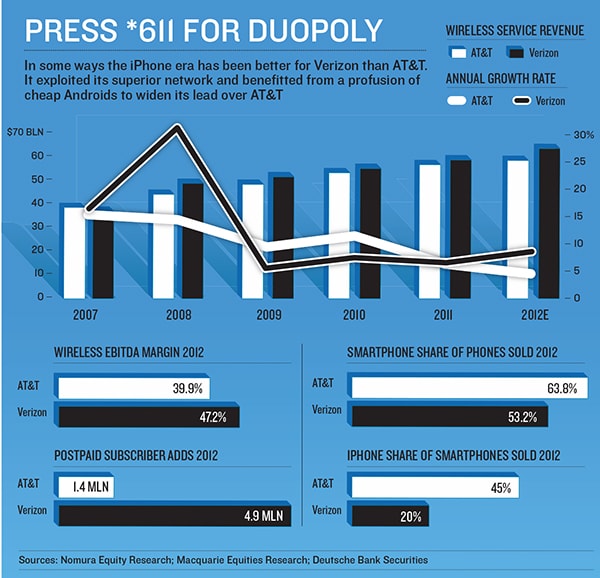

And six years to the month of the iPhone launch, smartphones are fast approaching saturation in the US, if they’re not there already. Nearly two-thirds of AT&T’s customers under contract (also known as ‘postpaid’) have smartphones, and almost half of those are iPhone users, compared with just over half and 20 percent for Verizon.

In 2012, AT&T is expected to sign up 59 percent fewer net new postpaid customers than it did in 2010. Verizon is up 38 percent in that period. “In some ways AT&T is a victim of its own success,” says Craig Moffett, a telecom analyst at Sanford C Bernstein.

Stephenson’s mantra is to ‘mobilise’ everything. AT&T is looking to work with farmers to plant wireless sensors near roots to determine when they need water and with automakers to push consumer apps into cars over its networks. It is testing a wireless home automation and security business in Atlanta and Dallas called Digital Life with an eye toward a national rollout this year. “We are sitting on top of some of the greatest demand that any industry has ever seen,” says de la Vega. “Those people who tell me we run out of revenue when we run out of humans, they just don’t get it. Data is going to surge.”

Not everyone is convinced. “The reality is that the growth of devices connected to the wireless network is slower than it has ever been,” says Moffett. “Postpaid subscriber growth in the US, including phones and every manner of tablet, laptop card and wireless dog collar, has slowed to a crawl, slipping below 1 percent annual growth for the first time.”

Stephenson pays no heed. In November, he announced a new, $14 billion three-year plan to expand its 4G LTE wireless network, bring fibre to more businesses and extend the reach of its U-verse broadband service. This lifts AT&T’s expected annual capital spending to $22 billion. It will even outspend Verizon on wireless capex for the first time this year.

Stephenson said he learnt from his mentors, former AT&T boss Edward Whitacre and Mexican telecom billionaire Carlos Slim Helú, that when you hit difficult times, it’s time to invest. Whitacre says that’s exactly what he told Stephenson: “Keeping going. Kind of by definition, if you’re not growing, you’re shrinking. Just keep going.” As for Slim, he has only praise for Stephenson: “He has a clear vision of AT&T and the global telecommunications industry.”

That vision began taking shape 16 years ago. The Oklahoma native joined Southwestern Bell in 1982 and did stints as CFO and COO. In 1996, after Stephenson returned from an assignment in Mexico, where he got to know Slim, Whitacre asked him to assemble a long-range view of the industry. Stephenson did it with the help of a consultant from Deloitte & Touche named John Donovan, whom he would hire a dozen years later as AT&T’s CTO. “We all believed data was going to be important,” Stephenson says. “I don’t think we had an appreciation for just how important it could become until 2007, when we launched the iPhone.”

For Stephenson it was the perfect time to introduce the ‘new’ AT&T. He insisted the iPhone be released under the AT&T brand rather than its subsidiary Cingular. “I don’t care if you have to go to every store in America and get a paper bag and paint a globe on it and put it over the signage in each store. We’re going to launch this under the AT&T brand,” he remembers telling his team. “And it was the smartest thing we ever did, because AT&T became synonymously branded with that Apple product at that moment in time.”

During the first year of the deal, AT&T sold the iPhone starting at $499 and agreed to give Apple an unheard-of cut of its customers’ monthly bills, estimated to be a $720 million slice of revenue. Once early reports on surging traffic came in, Stephenson knew he had an expensive hit on his hands.

“It went beyond any rational expectation we could have ever put together,” he says. He renegotiated with Jobs to end the revenue share and buy the phones up front for a reported $400 apiece and subsidise the new $199 cost with a two-year contract. AT&T ended up spending more than $70 billion on new equipment and capacity in the first three years after the launch but still got blamed, including by Jobs, for every dropped call.

Behind the scenes, Stephenson was seizing the moment to make AT&T ($127 billion sales in 2012) into a wireless innovator. The employee purchase programme was modified to encourage use of mobile devices. “Every CIO [chief information officer] in America said, ‘You’re not bringing those into our corporate environment’, my CIO included. And we said, ‘Yes, we are. Figure it out’,” Stephenson says. Cash registers are being replaced in its stores with mobile checkout, and by this time next year, technicians in AT&T trucks will be carrying iPads.

Stephenson’s one big strategic blunder was the proposed $39 billion takeover of Deutsche Telekom’s T-Mobile, the fourth-biggest US carrier. The deal was rebuffed by the Obama Administration and scuttled in December 2011. AT&T was forced to pay a $4 billion breakup fee, and Stephenson saw his compensation cut by $2.08 million for letting the prize slip through. He takes a moment to vent his frustration with policymakers.

While Apple and Google have made amazing advances in the mobile ecosystem, “none of this exists without the carrier environment, and a very healthy and flourishing carrier environment”, he says. “How do you make sure that kind of bandwidth and type of spectrum is out there and is available and is being put to use and constantly being invested in? That ought to drive every policymaking decision at the FCC [Federal Communications Commission].”

Stephenson said he took some time off, unplugging his devices and going through a “complete recalibration” of how to get the company where he wanted it to go. He came back in January 2012, promoted longtime operations chief John Stankey to chief strategy officer and set about the plan: Get spectrum, sell dying assets and invest heavily in growth businesses such as 4G wireless, corporate data clouds and high-speed fibre to businesses and homes.

AT&T spent the better part of last year piecing together deals for half of the 60 MHz it would have gotten with T-Mobile. It now says it has enough to handle data traffic on its network through 2017. It finally sold off a 53 percent stake in its shrinking Yellow Pages subsidiary to Cerberus for $950 million. It would have gotten a much better price if it had done the deal earlier.

Stephenson is also looking to John Donovan, who runs AT&T’s global network, to bring Silicon Valley-style invention to the company. Donovan pulled together a 16-member tech council in 2008 to brainstorm, and one of the first things they created was The Innovation Pipeline, or TIP. It’s a crowdsourcing platform used by more than 143,000 employees who offer up and vote on new product and service ideas and then get funding for them. One that got $450,000 is an app called Toggle, which lets you have both work and personal modes on the same device. You can flick between screens but keep photos, files and contacts separate.

Donovan also oversaw the creation in 2011 of the Foundry, a set of tech centres in Palo Alto (California), Plano (Texas), and Israel, where non-AT&T developers come in. AT&T has heard 1,000 pitches, with 29 projects deployed and $100 million invested from AT&T and other Foundry sponsors such as Intel, Microsoft and Ericsson.

Sixteen years after he put together that long-range view of the industry, Stephenson says the wireless world he envisioned is here. New 4G devices like Samsung’s Galaxy camera, which uploads photos directly to social networks over AT&T’s network, hint at even more intriguing devices and services to come.

“Our customers think of us as a wireless company first and foremost,” Stephenson says when asked if his 2007 wireless reinvention has been a success. “It has not been easy. It hasn’t been painless. But I think that’s where we are.”

(This story appears in the 08 March, 2013 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)