An alligator wrestler, a casino boss and a $12 billion American tribe

How the Seminole Tribe of Florida went from being a band of outcasts living in the Everglades to the multibillionaire owners of an iconic global brand

Seminole Gaming chief executive James Allen outside the seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, florida. He's as serious as a heart attack about building the Seminoles' fortune

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

Jim Allen has been up since 3 am leaving voice mails for himself at the office and is now weaving through the flashing slot machines and blackjack tables on the floor of the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, Florida. With a reporter in tow, he is recounting how a Native American tribe managed to beat out 72 bidders, including private equity giants and multinational hospitality companies, to acquire the rock ’n’ roll restaurant, hotel and casino company a decade ago under his direction. “At first the tribe thought maybe I had lost my mind and gone crazy,” Allen says.

Crazy like a fox. The hard-charging 56-year-old has helped create unimaginable riches for the 4,100-person Seminole Tribe of Florida as chairman of Hard Rock International and chief executive of the tribe’s gambling operations. What’s immediately clear when you meet Allen is that he’s unapologetically hands-on. Walking through the hotel, one employee points out a large black octopus chair in the lobby bar and jokes he can’t believe Jim wanted that there. Allen shrugs this off and brags that he’s behind every design detail down to the “admit one” tickets on each new roll of toilet paper in the rooms. He explains that his late arrival that morning was due to a spot check of the men’s bathroom, after which he was asked to look into an employee squabble that took him out to the parking lot.

“I’m serious as a heart attack,” says Allen, who’s actually had two heart attacks and bypass surgery in the past three years and still routinely pulls 16-hour days. “Some people talk about it, some people make excuses, some people get it done. I prefer the latter category.”

Though he doesn’t have a drop of Seminole blood in his veins, Allen may well be the single best champion of indigenous peoples since Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, which sought to conserve and develop tribal lands and culture. But unlike social programmes mandated by the federal government, Allen’s improvements are purely the result of the pursuit of profit. At the behest of the Seminoles he presides over an expanding, privately owned global business that spans 71 countries and owns 168 Hard Rock cafes, 23 hotels and 11 casinos. Including franchisee sales, system-wide revenue is slightly more than $5 billion. Another 25 Hard Rock hotels are in the pipeline—from Dallas to Dubai to Shenzhen—and the company just acquired the rights to the flagship Hard Rock Las Vegas. In November New Jersey voters will decide whether Allen can build a Hard Rock Casino with 4,000 slot machines, 2,000 table games and a giant guitar out front adjacent to MetLife Stadium in the Meadowlands just a few miles from Manhattan.

And though the Seminoles are guarded about the information they share with outsiders, it’s clear that their rapid expansion in the hospitality and gambling industry under Allen’s stewardship has created a money machine that generates operating profits estimated at $1.5 billion per year. That’s enabled the tribe to send revenue-sharing cheques to the state of Florida amounting to more than $1 billion over the past five years.

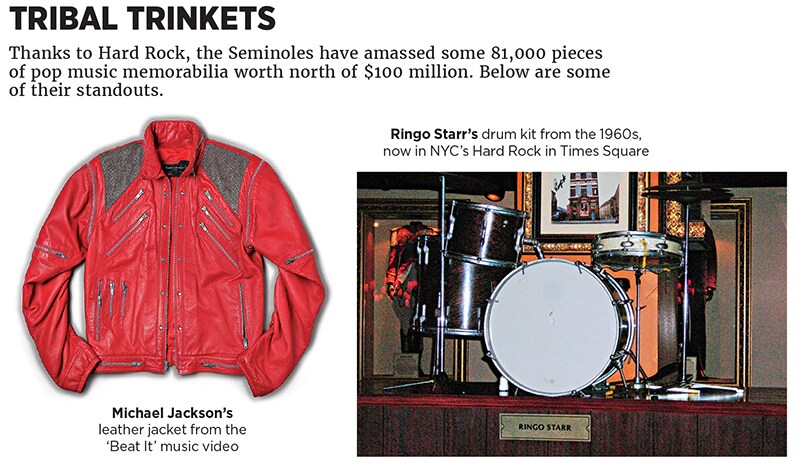

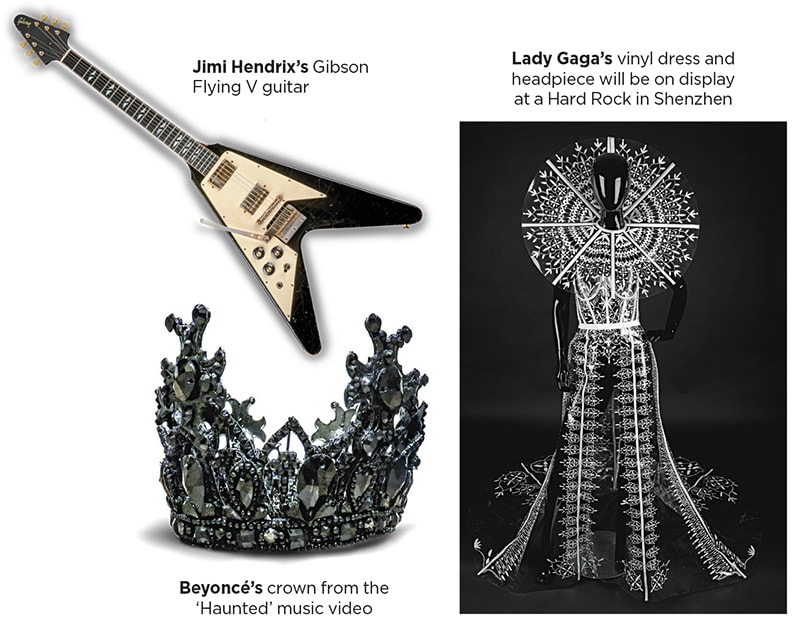

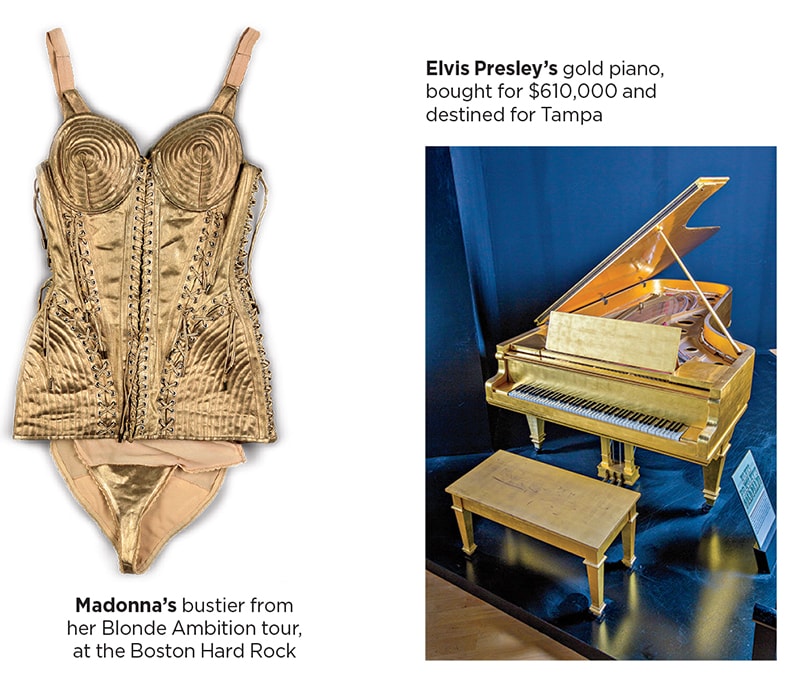

And for the Seminole people? Today every man, woman and child in the tribe receives biweekly dividend payments totalling about $128,000 a year. Indeed, by the time a Seminole child today turns 18, she is already a multimillionaire, thanks to tribal trusts that prevent children or their parents from touching the funds until adulthood. Applying industry multiples to the Seminoles’ hospitality and gambling businesses would put the tribe’s net worth at about $12 billion, including some 81,000 pieces of pop music memorabilia—stuff like Michael Jackson’s red leather jacket from the ‘Beat It’ video and John Lennon’s handwritten lyrics to ‘Imagine’—valued at more than $100 million.

Tribe member Tina Osceola, 49, remembers a time when selling tribal souvenirs to tourists sustained many of its members but now credits gambling riches with paying for her undergraduate and graduate school education. “Allen never stops,” she says, “and, frankly, I don’t want someone who stops.”

Chief executive Jim Allen is the man who made millionaires out of the entire Seminole Tribe of Florida, but the tribe’s longtime, controversial, alligator-wrestling chief, James Billie, deserves even more credit for sparking the entire $33 billion Indian gambling industry to begin with. Country singer, alligator wrestler and on-again, off-again chief of the Seminole Tribe of Florida Jim Billie is widely considered to be the father of Indian gambling

Country singer, alligator wrestler and on-again, off-again chief of the Seminole Tribe of Florida Jim Billie is widely considered to be the father of Indian gambling

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

It’s just after lunchtime, and Billie ambles into the air-conditioned lobby of the gleaming, four-storey Seminole Tribe headquarters built on an old pig farm in Hollywood, greeting people with a fist bump. In just a few weeks Billie, 72, will be ousted as chief of the tribe for the second time in four decades. But for now it’s a warm day in August, and he’s just arrived from his home on the nearby Brighton Reservation on one of the tribe’s red, yellow and white helicopters. Clad in a short-sleeve polo, Under Armour sweatpants and his favourite penny loafers, he stops to visit with the members of the tribe in his office before settling in at the head of the table in a dimly lit, windowless conference room.

When his phone rings (the ringtone is the ding-ding-ding of a slot-machine jackpot), he ignores it and says it’s someone calling to ask for a $30,000 loan. That’s why he no longer visits people on the Seminoles’ six Florida reservations. All they want is money, he says. “Maybe it will be my political demise, I don’t know,” says Billie, who, as chief, has had at his disposal discretionary funds estimated to be in the tens of millions annually. It’s a prescient statement. At the end of September tribal members filed a recall petition, vaguely citing various issues with Billie’s policies and procedures. The four other leaders in the tribal council unanimously voted to remove Billie from office.

It isn’t the first time Chairman Billie has been ousted. He led the tribe from 1979 to 2001 before being voted out amid sexual harassment allegations (the charges were later dropped) and charges of financial malfeasance. (Billie later said his removal was due to bad blood over his increased scrutiny of council member spending.) Then, after a decade in exile, he was elected chief again in 2011 and reelected in 2015. Billie vows to run again, in the next election.

He is, after all, a genuine folk hero. Born a “half-breed” in 1944 on a chimpanzee farm in Dania Beach, Florida, where tourists would pay to gawk at both the apes and the Indians, Billie tells of how he was taken from his mother as an infant to be drowned in the canal, only to be rescued by a tribal matriarch. After his mother died, when he was nine, Billie learned to wrestle alligators for tourist tips. In his early 20s he enlisted in the US Army and served two combat tours of Vietnam. He eventually became a touring country singer with such hits as ‘Big Alligator’, which is laced with lyrics in his native Miccosukee tongue.

Billie’s Rambo-with-a-heart reputation helped him get elected chief in 1979. On his first day in office someone handed him a stack of papers describing something called high-stakes bingo. It claimed that through gambling the tribe could make $3 million in six months. “That was a lot of money back then, so I thought maybe we should try it,” he explains. To finance the venture, he borrowed funds from an associate of the organised-crime figure Meyer Lansky, according to a Pennsylvania Crime Commission report in 1992.

Soon crowds of locals and snowbirds were flocking to the Seminole Tribe’s 1,200-seat Hollywood bingo hall. Gambling was illegal in Florida, and the county sheriff promptly threatened to shutter Billie’s budding operation. Instead of backing down, he defiantly led his tribe to court and won a landmark case in 1981, asserting the sovereign status of Indian nations in such matters. Congress gave its stamp of approval to tribal casinos with the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988. Today 234 Native American tribes are hauling in $33 billion a year from gambling, according to the Indian Gaming Industry Report, and they all have James Billie to thank.Billie rarely drinks and doesn’t gamble, but he’s passionate about flying planes and helicopters and has a reputation as a womaniser with a penchant for telling off-colour jokes. His life philosophy mirrors his approach to business: It’s easier to ask forgiveness than to beg for permission. For example, in 1980, a mass Seminole grave was discovered in Tampa, right where the city had planned to put a parking lot. Billie worked out a deal to swap his tribe’s sacred burial grounds for an alternative location not far from Interstate 4, where he promised to rebury his ancestors’ remains. Little did the Tampa officials know that Billie would also turn the site into another gambling hall. The Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Tampa now accounts for 40 percent of the Seminoles’ $2.2 billion in annual gambling revenues.

During his reign as Seminole chief Billie enjoyed considerable riches, including a 47-foot yacht and the use of a small fleet of helicopters and planes, one of which was a jet once owned by Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos. As hundreds of millions of dollars flowed through the tribe over the last four decades, tribe members and their employees have been accused of everything from tax fraud and money laundering to being connected to organised crime. During one court proceeding in 2002 a tribal council member admitted that he personally spent $57 million over three-and-a-half years. “I bought [Lexuses] for everybody,” he said. Billie himself has also been a target of law enforcement, including the FBI, but nothing has ever stuck, and Billie has never been criminally indicted. Luck has played a role. In the early 1980s he shot, skinned and ate an endangered Florida panther (whose flavour he jokingly likens to a mix of manatee and bald eagle) near his home on the Big Cypress Reservation. But after a game warden mishandled evidence, the jury became deadlocked and Billie walked.

The tribe’s connection to Hard Rock began in 2000 when a Baltimore real estate developer, the Cordish Cos, presented Billie with several licensing options for the two gargantuan hotels and casinos Cordish was building for the tribe in Tampa and Hollywood. It was down to a choice between Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville and the Hard Rock Cafe. Billie chose the latter because, he says, Buffett once dissed him during a chance airport meeting. “I waved to him, and he didn’t wave back,” says Billie, who walks with a cane after a stroke but still brims with the machismo that led him to lose his right ring finger while wrestling an alligator at age 55.

But just around the time the Seminoles were breaking ground on their new Hard Rock properties in Hollywood and Tampa, Billie was forced out amid tribal turmoil. Billie spent the next decade building traditional thatch-roofed chickee huts and helping to raise his two young children, whom he had with his third wife, Maria, never dreaming that his Hard Rock deal would bear such fruit. “Back then I thought Hard Rock was gonna be good, not great,” he says. But then again, he had only just begun to deal with casino manager extraordinaire Jim Allen.

One glance at James Francis Allen in his tieless blue suit and his slicked-back grey hair and you know he was born to be a big-time casino boss. He is the product of a working-class family from Atlantic City, New Jersey. When he was 13, he persuaded the pizzeria owner at the end of his street to give him a job even though he wasn’t hiring. The owner took a liking to him and enlisted him to wash his Mercedes-Benz every day—a job Allen took so seriously that he meticulously applied mink oil to the leather interior and spent an hour polishing each wheel on Saturdays. He then got a job as a cook at Bally’s Park Place casino to help out his financially struggling family. When Allen’s dad died from cancer in 1979, he recalls, bill collectors phoned the house so often that friends and family were advised to let the phone ring twice, hang up and call again if they wanted someone to answer. “I was committed 100 percent at the youngest of ages to say that will never be me,” Allen says.Allen never accomplished much in terms of formal schooling, but he worked harder than anyone else. At Bally’s he was promoted to cook and drew management’s attention when he helped figure out how to use a kitchen cost-management software that proved difficult to master. After he was promoted to the office job of menu analyst, the executive chef demanded that he return to the kitchen. Allen managed to do both jobs, earning double-time pay.

In 1985 he moved down the boardwalk to Hilton as a purchasing manager. Donald Trump took over the property after Hilton was denied a gaming license, and Donald’s then-wife, Ivana, deeply impressed by Allen, personally urged him to stay with the company. Over the course of eight years, until 1993, Allen held various management positions in the Trump organisation and eventually helped oversee the operations of Trump’s three Atlantic City casinos. From there Allen went on to open and manage casinos in New Orleans for Hemmeter Enterprises, and for South African real estate magnate Sol Kerzner he opened Mohegan Sun in Connecticut and Atlantis in the Bahamas.

Allen was hired by the Seminoles in 2001. Under his direction, the beautiful new $400 million properties in Hollywood and Tampa opened in 2004. There was one big problem, though. Under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, the casinos couldn’t have blackjack, baccarat, slot machines or any other lucrative ‘Class III’ games until they got permission from the state.

Bingo, which is considered Class II because players are pitted against each other rather than the house, was already well established on the Seminole reservations in Florida, but then-governor Jeb Bush had no interest in allowing full-on gambling in his state. It would take years, and involve fending off a challenge from Senator Marco Rubio, before the tribe would come to an agreement with the state allowing Class III gambling. So in 2003 Allen boldly circumvented regulations by persuading several gambling manufacturers to create a brand-new type of slot machine that had the look and feel of sophisticated Las Vegas-style Class III slot machines but were actually using the same math as a legally permissible Class II machine. In other words, under the hood these were bingo drawings. Connected by a central server, players would be competing for prizes against other players at Seminole casinos rather than playing against the house. Most players, even seasoned ones, would be none the wiser.

“This was monumental,” says Brad Buchanan, who spent 13 years with the tribe as its chief financial officer before retiring last year. “Jim will drill and drill and drill until he hits the concrete, and when the drill bit breaks he will replace it with another and keep going.”

Thanks to Allen’s genius, the two casinos were soon among the most profitable in the country. By 2006 the tribe had become the single biggest Hard Rock licensee and was forking over $21.5 million a year in licensing fees to its British parent company, Rank. From Allen’s vantage point, Rank was taking advantage of the Seminoles. The deals were structured for hotels, not casinos. “If you think of a busy hotel, it’s doing $10 million or $15 million a year,” Allen says. “A busy casino does $20 million to $70 million a month.”

In late 2006 he persuaded the tribe to pay $965 million to buy Hard Rock International from Rank, financed with $500 million in debt. “When we looked at the brand and how much we had riding on it,” Buchanan says, “we wanted to make sure it ended up in the right hands.”

There is nothing rock ’n’ roll about Hard Rock’s operations under Allen. Almost immediately he attacked the cafes’ menus, nixing subpar ingredients like frozen burger patties. Undercover employees known as “mystery diners” were dispatched to maintain quality control. “I don’t want to say anything bad about Rank, but they were operating for quarterly profits,” says Gary Epstein, a lawyer who worked on the acquisition.

While the cafes still account for most of Hard Rock’s $665 million in revenue, Allen struggles with the fickleness of the casual dining business, and the company is saddled with a tourist trap image. In the first half of 2016 same-store sales at the cafes fell 1.9 percent in North America and 5.4 percent in Europe.

Allen’s big push is into hotels. He has opened 16 properties another 25 are in the works, and he sees room for at least 50 more in short order. Each is more audacious than the last: A sprawling beach-front hotel in Cancun, a 101-storey skyscraper in Dubai, and a 372-room hotel in Berlin overlooking Checkpoint Charlie. That’s not even counting the 100 hotels under a different brand name that he is planning to open in China.

“It’s not that we’re abandoning cafes, we’re just expanding our horizons,” Allen says. “When you look at the revenue you can generate in the hospitality sector, the numbers are just so much greater and, frankly, so are the margins.”

Casinos are also high on Allen’s priority list, but they are harder to pull off quickly because of politics. In 2013, for instance, voters in Massachusetts rejected his proposal for an $800 million hotel, casino and entertainment complex, and in 2015 Wisconsin governor Scott Walker rejected a plan to build a similar complex in partnership with the Menominee Tribe. The fate of the Meadowlands Hard Rock Casino will be put before New Jersey voters in November.

Hard Rock sometimes takes a sliver of equity in its hotel and casino deals, such as its 16 percent stake in the Meadowlands venture, but like other iconic brands it mostly relies on partnerships and other people’s money for rapid global expansion. Hard Rock International represents the tribe’s biggest effort to diversify away from its seven Florida casinos. Unfortunately, the tribe’s exclusive right to blackjack, baccarat and other casino table games, where the player bets against the house, technically expired in Florida in 2015, and the tribe is suing the state in federal court over its failure to negotiate a renewal.

Allen, who calls during his lunch break after four hours of testimony in Tallahassee, is already focussed on his next project: Hard Rocks west of the Mississippi. “This is the first time in 30 years the brand is 100 percent controlled by one company,” says Allen, who drives a royal-blue Maserati and lives in a $10 million waterfront mansion in Fort Lauderdale with his yoga-instructor wife. For his efforts, Allen earns an undisclosed salary and bonus from the Seminoles’ casino business and has a small equity stake in Hard Rock International estimated to be worth about $75 million.

In the 15 years since Allen arrived, Seminole tribe members’ annual dividends have risen from about $30,000 a year to an estimated $128,000, plus access to free private school and college tuition, universal health care and elder care. All are offered employment with the tribal government, and the reservations are dotted with oversize houses and late-model cars. The unceasing flow of wealth has not been without its downsides, however: Drug and alcohol abuse remains a problem, and a low percentage of adults have a college education. Fewer young people are interested in traditional tribal crafts or events like the Miss Seminole pageant or alligator wrestling. And since anyone with 25 percent Seminole heritage can qualify for a dividend, the tribe faced a rash of “dividend babies” until about four years ago, when Chief Billie halted payments to those under 18.

It’s becoming even more vital that the Seminoles learn to manage and live with their riches, as the amount of cash flowing into tribal coffers will likely increase.

Today not a penny of members’ dividends comes from Hard Rock International, which is worth an estimated $1.6 billion. Almost all of the tribe’s $525 million in annual dividends flows from the Seminoles’ seven Florida casinos, which are worth an estimated $10.4 billion. Allen says he has set up Hard Rock not only for growth but also for an eventual IPO, should the tribe desire it.

Allen’s employment contract expires in 2018, but even with the unpredictability of Seminole politics, his renewal seems a certainty. “The business has really taken off since my arrival,” he says. “Whenever I do leave, I want them to be able to say that was one white guy that was honest.”

First Published: Nov 30, 2016, 06:17

Subscribe Now