Airbnb: New tricks for an old unicorn

After reinventing hospitality a decade ago, it now needs to quickly expand to support its $31 billion valuation before an expected IPO

Ten-figure troika: From left, Airbnb’s billionaire co-founders Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia and Nathan Blecharczyk photographed at their San Francisco headquarters

Image: Jamel Toppin for Forbes

For a full 32 seconds, the notoriously fidgety Brian Chesky sits still. Planted under a fake tree in a bespoke conference room at Airbnb’s headquarters in San Francisco, the 37-year-old CEO is intently focussed on the iPhone in his hands. It’s playing a marketing video showing goats mingling with guests during an Airbnb Experience at a Northern California animal sanctuary, offered as part of the company’s two-year old tour guide business. A sheltie named Osso (short for Ossobuco) sits under the conference table licking the billionaire’s black sneakers. As the sound of the last bleat fades, Chesky seems moved. “Wow,” he says to the eight employees closely watching his reaction. He releases a deep breath. “I feel something.”

Maybe this is progress, a return to the magical feeling Chesky wants Airbnb guests to feel. Airbnb became great by offering unique, affordable accommodations in a cookie-cutter world. And, in the decade since its founding, it has ridden a generational change in social attitudes—with digital natives suddenly becoming comfortable accepting rides from strangers, swiping right for hookups and sleeping in spare bedrooms—to a $31 billion valuation, raising over $3 billion in outside money. Along the way, Brian Chesky and his two co-founders, Joe Gebbia and Nathan Blecharczyk, have each accumulated a $3.7 billion fortune from their Airbnb shares, and the startup they built has joined the rarefied group of companies—Google, Xerox, Uber—whose names have become verbs.

But with all that money comes a unique challenge. Call it the curse of the unicorn: How can Airbnb justify a valuation that is higher than Expedia, Hilton or American Airlines? Although Airbnb has a $3 billion war chest, it earned just $100 million last year on a cash flow basis from $2.6 billion in revenues, or about 4 percent. (Its larger, publicly traded competitors have margins of about 27 percent). How can Airbnb keep growing—amid sharpening competition and increasing regulatory scrutiny—and deliver the 10x return their venture capitalists demand? Making it all the more pressing is the prospect of an IPO, said to be on track for as early as mid-2019.

undefinedAirbnb has joined the rarefied group of companies—Google, Xerox, Uber—whose names have become verbs[/bq]

It’s particularly difficult for Airbnb, because unlike, say Google, which has revolutionised everything from search to phones to cars, up to now Airbnb has largely been a one-trick pony. It connects people who have vacant homes and apartments with people wanting to rent them. That’s it. Hence Airbnb’s newfound interest in selling guided tours with Experiences or helping with restaurant reservations through its partnership with Resy.

Compounding matters is a weak executive team that lacks a chief financial officer and a chief marketing officer less than a year from its goal of being IPO-ready. Then there’s Chesky, a CEO who—despite accepting billions from investors—is not putting their interests at the front of the line.

“The scorecard for companies has changed,” Chesky says. “Before, it was really about financial metrics, and I think now companies are realising we have a greater responsibility to society to make sure life is great.”

The plan, such as it is: Drawing loosely on Amazon for inspiration, Chesky wants Airbnb to be an everything store, but for travellers. Chesky hopes a billion people a year will use Airbnb by 2028, a giant leap up from the total of 400 million who have used the service during its first ten years (roughly 100 million people have stayed in an Airbnb so far this year). Following the Bezos blueprint, he’s rewiring Airbnb’s technology so that it can quickly scale up hundreds of businesses and categories faster than ever before.

“At some point, the law of large numbers means that you just need to plant more seeds,” Chesky says.

But Chesky also worries that runaway growth could imperil Airbnb’s uniqueness. As a result, he is trying to position Airbnb as what he likes to call a “21st Century Company”, one that’s beholden not only to financial results but also to other stakeholders like guests, hosts, employees and cities. Chesky views this not as touchy-feely corporate-culture stuff but as survival: Decision-making must be driven by what’s best for everyone in Airbnb’s community. Only then will his investors thrive. “The public is not going to put up with companies in the next 50 years that are only kind of myopically, narrowly focusing on the very short term or just a few parties,” Chesky says.

The result is tension between Airbnb’s need to scale rapidly and Chesky’s desire to take it slow and build something that’s responsible and sustainable. “The reality is that you’re not going to be around long-term unless you’re able to grow and generate attractive economics,” says Kenneth Chenault, the former American Express CEO and an Airbnb board member. “You’re also not going to be around long-term if your brand is not meaningful in people’s lives.”

Knock twice on the bookcase and a hologram of Joe Gebbia appears. It’s a parlour trick of the real Gebbia, the 37-year-old Airbnb co-founder, as he settles into a conference room that is a mock-up of his old apartment, half a mile northwest of the company’s San Francisco headquarters. Behind him, the ghost version of Gebbia drones on: “You’re standing on the exact spot where we put the first three air beds . . .”

It’s a founding story that has achieved mythical status in Silicon Valley and remains at the core of Airbnb’s identity. Gebbia and Chesky, graduates of the Rhode Island School of Design, were short on rent, so they charged people visiting San Francisco for a design conference to sleep on an air mattress on their floor in 2007. They tapped a third friend, Nathan Blecharzyck, to help them build a website.

Originally called Air Bed and Breakfast, the startup wasn’t an overnight success. After 12 months, it was doing only 10 or 20 reservations a day. But the trio were already looking for outside money: In June 2018 they sought introductions to seven angel investors and were rewarded with five rejections and two ignored emails. The ask? $150,000 for 10 percent of the company, a position that, undiluted, would be worth over $3 billion today. Broke, the founders collected credit cards like baseball cards, organising the maxed-out plastic in binders. The biggest problem: Lack of trust. People weren’t comfortable inviting strangers they met on the internet to stay in their homes.

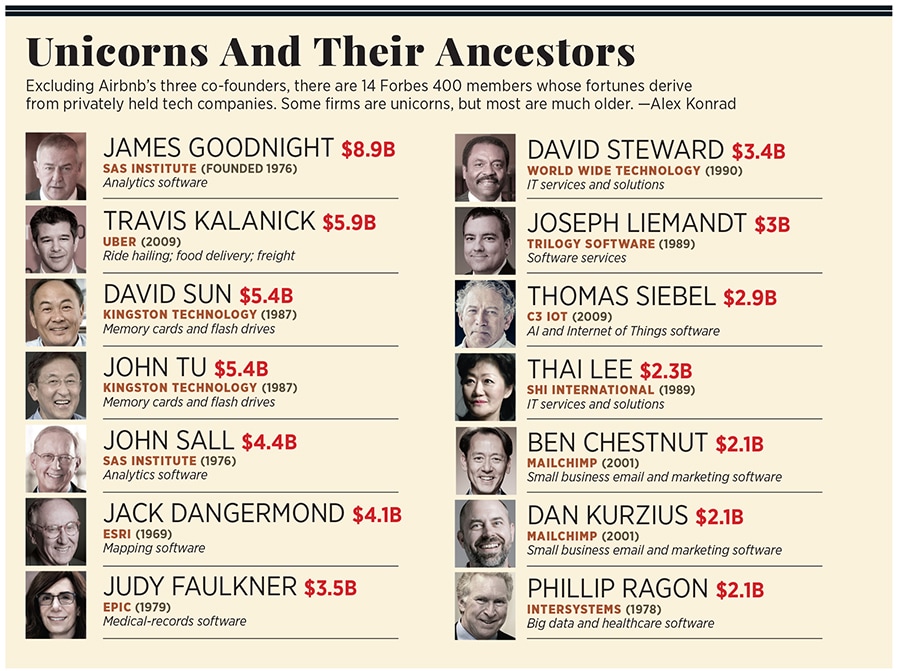

“It was a real battle to figure out how can you cross this bias that was working against us, that strangers equal danger,” Gebbia says. “It’s something that we’ve all been taught since we were kids.” Images: Courtesy: Dangermond: Esri Liemandt: Trilogy Steward: World Wide Technology Kalanick: Lucas Jackson / Reuters Goodnight: Jason Arthurs / Reuters Chestnut: Jamel Toppin Lee: Jonathan Kozowyk Siebel: Timothy Archibald Ragon: Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe / Getty Images

Images: Courtesy: Dangermond: Esri Liemandt: Trilogy Steward: World Wide Technology Kalanick: Lucas Jackson / Reuters Goodnight: Jason Arthurs / Reuters Chestnut: Jamel Toppin Lee: Jonathan Kozowyk Siebel: Timothy Archibald Ragon: Pat Greenhouse/The Boston Globe / Getty Images

The founders couldn’t fix the problem from their desks in San Francisco. They began staying with Airbnb hosts to learn what needed to be done. They built out a peer review system so people could rate each other, added round-the-clock customer service and worked on the quality of the photos. The financial meltdown of 2008 also pushed travellers to tighten budgets, and cash-strapped hosts were more willing to brave “stranger danger” in order to earn a little extra income.

Early on, Airbnb dropped the requirement that guests had to sleep on air mattresses and be served breakfast, and everything from backyard treehouses to single bedrooms in a shared apartment was soon listed on its website. By 2013, Airbnb had 500,000 listings. Now it counts over 5 million.

Those folks typically learnt about Airbnb by word of mouth—even today, the company spends more than 90 percent of its advertising budget on attracting the guests, not the hosts. That strategy has worked so far. In 2008, roughly 100 people stayed with Airbnb on its peak night. In August 2018, nearly 10 years later, 3.5 million people stayed with Airbnb on its best night. (The average is around 2 million.)

After so many years of effortlessly signing up hosts, Airbnb is facing an unexpected supply problem. The reason is twofold. First, its success has attracted deep pocketed competitors. Booking Holdings—the $12.6 billion (2017 revenue) owner of properties like Priceline and OpenTable—and Expedia (2017 revenue: $10 billion) have started emphasising apartments and vacations rentals on their sites. This spring, Booking Holdings split “alternative accommodations” into their own category, reporting for the first time that it has 5 million listings, the same number Airbnb has.

undefinedIn many ways the Amazon comparison is a stretch. Retail is a $5.8 trillionmarket in the US, much larger than travel, even in its broadest sense[/bq]

Secondly, local authorities are starting to crack down. The beefs range from charges that property owners are using Airbnb to create unregulated hotels to accusations that the company is exacerbating housing shortages. Cities like Berlin, Santa Monica and San Francisco all saw monthly listings drop—in some cases by more than 30 percent—after strict regulations were passed, according to the Denver-based data analysis firm AirDNA. New York City and Paris have also targeted the company. In Japan, a change in the law in June forced Airbnb to cancel thousands of bookings and establish a fund of $10 million for inconvenienced customers.

“When something comes easy, you don’t have to build the muscle,” Chesky says. “And what came easy was a lot of listings.” So, in February, Airbnb expanded its focus to be more welcoming to established operators, from bed-and-breakfasts to vacation rentals and even boutique hotels, giving each a category on its website. It’s an obvious way to grow, even if it tends to undermine what purportedly makes Airbnb unique.

One advantage: Airbnb takes a smaller cut from hosts, only 3 percent compared with the traditional 15 percent an online travel agency like Booking might charge. “I wouldn’t say they’re a better version. They’re a cheaper version,” says Alec Shtromandel, who manages rooms for the Gowanus Inn boutique hotel in Brooklyn on Airbnb.

Airbnb may be cheaper than its competitors, but it can’t yet offer their breadth. Booking Holdings’ growth has been marked by lots of strategic acquisitions, and it already owns a lot of the pieces that Airbnb is just now starting to build. Booking has Kayak for flights, OpenTable for reservations, Rentalcars.Com for transportation, Agoda for travel in Asia and Priceline for discounted bundles.

Glenn Fogel, the CEO of Booking Holdings, says his goal for the next ten years is to tie all the parts together to make it seamless to book a trip from start to finish. “Yes, this is going to be a hard thing to do, but the people who have the highest chance of achieving it are the people who have the scale and the experience and have a lot of the foundational blocks already,” Fogel says. “That would be us.”

Chesky shares that vision of a seamless trip and sees the obvious acquisitions—big chain hotels, mainstream tour operators, even transportation companies—but he’s not interested in buying his way to growth. Instead, he refuses to compromise on what he insists is Airbnb’s point of differentiation: The feeling of belonging.

“I think the centre of gravity for Airbnb should continue to be offering unique experiences that do not exist anywhere else on the internet,” Chesky says.

If the dream is the “Amazonification” of Airbnb, Chesky is aware that he has a long way to go. He’s poached one of Bezos’ top lieutenants, the former head of Prime, to try to turn the Amazon analogy into a reality. Greg Greeley spent 18 years at Amazon before joining Airbnb in March to run its Homes division, which oversees its core rental business. When he joined Amazon, people wondered if it could sell anything more than books. Now Greeley is at Airbnb when it needs to execute a similar expansion. “The analogy to 20 years ago and another ‘A’ company is not lost on me,” he says. “There’s this Amazon-size opportunity of travel out there.”

But in many ways the Amazon comparison is a stretch. Retail is a $5.8 trillion market in the US much larger than travel, even in its broadest sense. Amazon sells things like books, clothes and garden tools—all mass-produced commodities. Airbnb wants to be the exact opposite. “One of the most popular listings on Airbnb is a mushroom dome,” Chesky says, referring to a tiny, geodesic-dome-topped cabin that rents for $130 a night along the California coast. “And unfortunately, no matter how successful it is, we can’t just make a million more of them. So we’re the kind of business that has to get into a lot of things, because everything we do can’t get so big, just by definition, it’s finite.”

Airbnb’s first big expansion attempt is Experiences, its take on the highly fragmented guided-tour market. Just as Etsy turned crafts into e-commerce and Uber turned anyone with a car into a private driver, Experiences wants to let anyone from a sous chef to a yogi run an online tour business. Still, how big is that market? “The limitation is not in space,” says Joe Zadeh, who runs Experiences for Airbnb. “It’s time.”

Launched in November 2016, Experiences has been a slow burn. The original idea of three-day, fully planned-out itineraries was too expensive and time-consuming for Airbnb’s budget-travel audience. It switched to shorter options but quickly ran into a quality problem. While homes aren’t vetted before they’re listed on Airbnb, that doesn’t work for hosted tours. Homes have basic architectural standards, including being livable in the first place. Random tours don’t, and Airbnb hosts went wild. One of the first Experiences, rolled out when the product was still in beta, turned out to be a woman who would yell at guests as they picked up trash on a San Francisco beach for an hour. An experience, for sure, but not the kind Airbnb was looking for.

The need to vet tour guides slowed Experiences down, but growth has accelerated in 2018. After launching with 500 Experiences in 12 cities two years ago, there are now 15,000 Experiences in 800 cities around the globe. The company takes 20 percent of each reservation, which added about $2 million in revenue last year. That’s not nothing, but it’s a rounding error for a company the size of Airbnb. According to sources, Airbnb spent more than $100 million to develop the product. Still, things might be looking up: Forbes estimates Experiences could hit $90 million in sales this year, leaving Airbnb an estimated $18 million cut. Airbnb disputes both the revenue and the loss figures but won’t give specifics.

In December, Chesky gathered his co-founders to brainstorm guidelines that he says will help future decision-making as the company seeks to follow metrics beyond financials. “If you have a greater responsibility,” Chesky says, “the question is, well, who do have responsibility to?”

For most CEOs, particularly ones looking to go public in the near term, investors would be the obvious choice. But Chesky is not most CEOs. In addition to looking after investors, Airbnb will also measure progress with regard to four additional stakeholders: Employees, guests, hosts and cities.

Airbnb hopes this will ease acceptance of some unusual corporate initiatives, like asking the SEC to allow Airbnb to grant its hosts stock as if they were employees and to offer them low-cost home improvement loans. But it also reflects a desire to remain true to its communal roots.

“We essentially have the Airbnb community as a virtual seat at the table, channelled through the founders, to say what are the right things to be doing to be growing,” says Reid Hoffman, the LinkedIn co-founder and Airbnb investor.

But that sort of inclusion will only become more difficult after an IPO. Airbnb had been searching for a way to remain private forever, but after talking with Morgan Stanley in the fall of 2017, the company realised there isn’t a private path forward. Instead, it is eyeing going public in mid-2019 at the earliest. The window will be short: In 2020, a large chunk of employee stock options will expire, vaporising their equity overnight.

Chesky is visibly squeamish when asked about going public. Too often, he says, companies lose track of the bigger picture and settle into a quarterly cadence. “The problem is some people forget they’re climbing the mountain in the first place,” he says.

“I’ve met a lot of CEOs that say, ‘I’m very long-term-oriented’ or ‘I want to be long-term-oriented,’ but they just have so many pressures and so many things that are in conflict,” Chesky says. “They say, ‘I want to serve the public interest,’ ‘I want to make sure our products are great for the world,’ but the only metrics they review at a board meeting are the metrics about the sales of the product essentially.”

Unorthodox words from the CEO of a company that might soon go public. Airbnb wants to write the rules to the game, but it will be up to investors to decide whether they are ready to play.

First Published: Nov 12, 2018, 16:01

Subscribe Now