A man, a can, a plan

John Hayes, the chief executive of venerable jar maker Ball, has abandoned glass and plastic. Is he crazy or just ahead of his time?

John Hayes

John Hayes

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes[br]In an 11-acre factory in Golden, Colorado, stacks of multicoloured empty cans loom 50 feet overhead. Every few minutes, a forklift zooms by to pluck future containers of Arizona iced tea, Truly spiked seltzer and Stem rosé cider. Here, 6 million can bottoms a day are forged and shipped off with tops to beverage producers. Every one is aluminium.

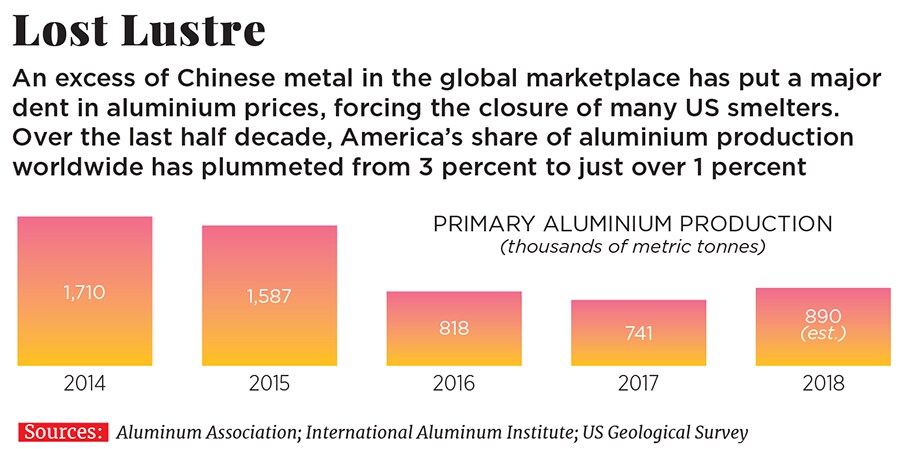

Ball Corporation made its name in the 1880s with glass mason jars and, in time, got into all manner of glass and plastic containers. But John Hayes, Ball’s chief executive, has sworn off those two materials. Apart from some aerospace work for the government, Ball gets all its $11.6 billion of revenue from aluminium containers—mostly for beer, soda and other drinks, along with some business in aluminium aerosol cans and in aluminium slugs for other can makers.

Isn’t this a bit risky, to make a 100 percent bet on metal when most of the beverage container market is still held by either glass or plastic? Maybe, but so far this bet is paying off. Vertical Research Partners’ Chip Dillon expects Ball’s earnings (adjusted for acquisitions and other things) to be up by 13 percent this year to $876 million. Since Hayes took over in 2011, the stock market has doubled Ball’s stock has tripled.

“In my 20 years at our company, I’ve never seen growth rates like this,” says Hayes, 53. Ball has tried 46 different business lines in its 139 years, and has entered and exited the plastics business three times. Hayes is confident aluminium will stick.

Hayes got degrees from Colgate (BA) and Northwestern (MBA) and in 1993 joined Lehman Brothers’ mergers and acquisitions office. He helped Ball, one of his early clients, exit its stagnant glass business.

Four years later Hayes was jet skiing in western Pennsylvania when he caught a nearby boat’s wake and lost control. He ended up with a series of facial reconstructions and bone grafts, spending two months in Chicago recuperating. Who came to visit him? Not a single Lehman colleague. It was David Hoover, Ball’s chief financial officer, who drove four hours from Muncie, Indiana.

“It was a pivot point for me,” Hayes says, his voice breaking. “I still get a bit emotional about that. It was one of those aha moments.”

Hayes quit Lehman a few months later, and in 1999 Hoover offered Hayes a job in corporate planning at Ball’s new headquarters in Broomfield, Colorado. By 2006 Hayes was overseeing Ball’s European business. Five years later he was running the whole company.

With 130 billion bottles a year in the US, plastic has half again the volume of aluminium. Glass wins out in more expensive beverages—it will be a long time before you see Château d’Yquem in a six-pack—but it seems the arc of history is bending toward Ball. In 2014, 32 percent of new beverage companies chose cans, according to an IRI research study. That number rose to 61 percent in 2018.

Aluminium wins on environmental grounds: Among beverage containers, the recycling rate in this country is 50 percent for aluminium, 42 percent for glass and 30 percent for plastic. “The whole sustainability agenda is only accelerating,” says Hayes. “I’d love to say it’s because of us. It’s not. We’re trying to take advantage of the current situation by helping our customers provide what the consumer wants.”

At least among younger consumers, cans are cool. Millennials grew up on Red Bull (a Ball client) and loved the sleek design of the can. They’ll displace the Baby Boomers, who gravitated to glass and plastic bottles in the ’70s and ’80s because “the can,” Hayes says, “was your mother’s or father’s package. It was old, it was tired, it was boring.” Now cans hold LaCroix sparkling water (from National Beverage, another Ball client) and novelty drinks like Truly (from Boston Beer).

What about the perception that cans impart a metallic taste (despite a coating of epoxy or polymer on the aluminium)? An interesting taste test by some academics three years ago found drinkers insisting, when they saw the stuff being poured, that bottled beer tasted better than canned beer. In a blind comparison, most drinkers couldn’t tell them apart.

Ball is fighting the perception. In 2002 it persuaded the Oskar Blues brewery in Colorado to put a new pale ale in cans, and now Ball has 70 percent of aluminium’s growing share of the craft beer market.

While awaiting aluminium’s conquest of packaged beverages, Hayes has another venture lined up. He displays a prototype aluminium cup, branded with Ball’s script logo. His hope is that this recyclable cup will replace the ubiquitous red plastic Solo. The millennials now busy outlawing plastic straws and bags just might go for this.

First Published: Jul 23, 2019, 16:58

Subscribe Now