Don't wait, innovate

Innovations are assumed to be non-incremental change or a breakthrough from the blue

It’s perhaps easier to define what innovation is—an idea that meets a need at an economical cost—than what it is not. But at a time when technological changes of all hues are easily branded as innovations (or, that other favourite, disruptions), it may not be a bad idea to zero in on what is not an innovation.

Vijay Govindarajan, professor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business and General Electric’s first chief innovation consultant, weighed in almost a decade ago when he declared that innovation is not creativity. “Creativity is about coming up with the big idea,” he wrote in Harvard Business Review. “Innovation is about executing the idea—converting the idea into a successful business.”

Then there’s that other debate between invention and innovation, the former being something that never existed before, and the latter a much-improved version of something that exists. So you could argue that while the computer is an invention, the Mac is not, as it is an improvement of the personal computer. Ergo, while Charles Babbage can be credited with creating (inventing) the computer, Steve Jobs was an innovator and doubtless a visionary but an inventor he wasn’t.

Because of the suddenness of the launch of an innovation and the innovator achieving rock star status, innovations are often assumed to be non-incremental change, or a breakthrough from the blue. On most occasions, they aren’t. What you don’t read about are the years spent in labs, and the midnight oil that was burnt in trying to find cost-effective, simpler and more accessible solutions.

Our special package on innovation helmed by Forbes India’s tech editor Harichandan Arakali delves for a large part into the work that’s underway at many such labs—from Walmart Labs India (essentially, the retailer’s India development centre) that creates solutions for some 11,000 stores worldwide to the more radical innovations (and inventions) for which MIT Media Lab has been a breeding ground to Intel India’s Maker Lab, which is working with the government on initiatives like Make in India and Digital India.

Intel India’s country head Nivruti Rai tells Sayan Chakraborty that the local operation drives both innovation and inventions. 5G, where Intel India is at the forefront, may be a classical example of innovation in progress. As Rai puts it: “1G was analogue, 2G was digital and 3G was where we started having data in phone calls. 4G is a lot of internet… and 5G… is a little evolutionary but a lot revolutionary.”

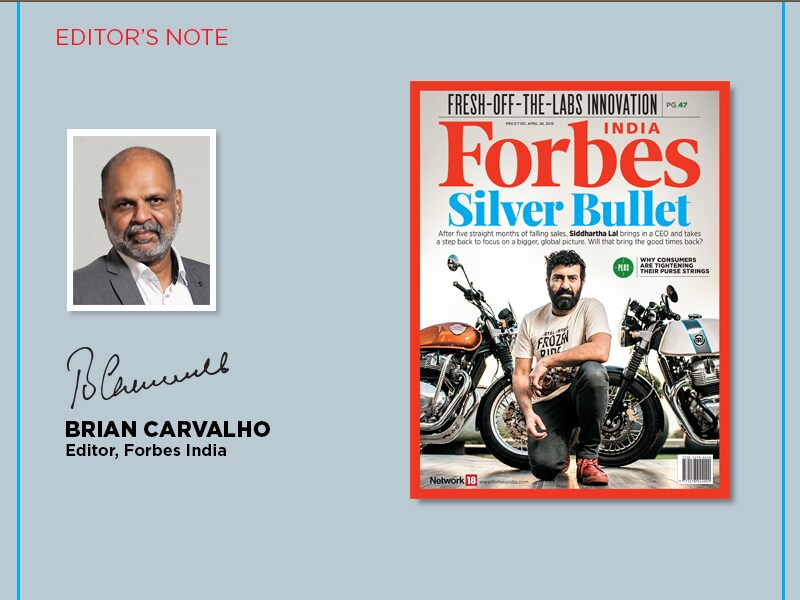

The proof of a successful innovation is performance, and for companies that often manifests itself in growth. When that growth tapers off, it’s innovation that can save the day. That’s what Royal Enfield’s (RE’s) Siddhartha Lal may well be counting on to counter the slowdown blues—after 10 years of gung-ho growth, the maker of the Bullet has been sputtering for five months now as its flagship product heads towards maturity in some major domestic markets. Lal has a plan—a long-term one—to squeeze growth out of global markets. But, to start with, RE’s got to get back in the fast lane back home. “Without India we cannot do anything. This is where our scale comes from,” Lal, who’s taken a step back to reimagine RE as a global player and appointed a CEO to inject fresh life into the company, tells Rajiv Singh. His ambition for the next decade is to become the first “premium consumer brand to come out of India”. Read Singh’s cover story to find out how Lal plans to get the thumpa-thumpa back.

Best,

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email:Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter id:@Brianc_Ed

First Published: Apr 12, 2019, 09:44

Subscribe Now