Contagious: Jonah Berger on why some things catch on

In his book Contagious, Jonah Berger explained why some things catch on. In this interview he decodes the science behind why some things go viral and how companies can use it.

Seoul is hardly the nerve center for all things cool. Yet when South Korean singer Psy released his sixth album in July 2012, one song—Gangnam Style—rocked music charts, made Psy a superstar and firmly pinned Seoul’s hip Gangnam neighborhood on the world map. Within a month of release, the music video, which had Psy doing an amusing ‘horse dance’, was number one on Youtube’s most viewed list and a couple of days later it topped the iTunes music video charts. By the end of the year, the song had topped music charts in 30 countries. US president Barack Obama tried to imitate Psy’s funny dance on a TV show, and UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon called the song a force for “world peace”.

Now was Gangnam Style such an out¬standing song? Maybe. Maybe not. So why did it become an overnight sensation?

Go back a couple of years and you’ll find similar instances—remember Los del Rio’s Macarena and Khaled’s Didi in the 1990s? And there is Susan Boyle’s more recent I Dreamed a Dream.

Why did these songs go viral? Most of us would attribute this to luck, chance or just random events. But Jonah Berger, Associate Professor of Marketing at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, firmly believes that there is a science behind why things go viral.

Still in his early thirties, Berger spent the last 10 years studying why things catch on. His research spans an array of areas: ranging from content on the internet, to brands, products and ideas, among other things. The result is a book titled Conta¬gious: Why Things Catch On, a New York Times bestseller.

Malcolm Gladwell is Only Partially Right

Back in the day when Berger was study¬ing at Stanford, his grandmother gave him Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling book The Tipping Point, a book that sought to ex¬plain why ideas, trends and behaviors go viral. Gladwell’s thesis is simple: the ‘tip¬ping point’ is a moment when “an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a thresh¬old, tips, and spreads like wildfire”. He likens it to an epidemic, albeit a “social epidemic”, propagated in large part by people he classifies as connectors, mavens and salesmen. These people help spread the idea. Gladwell’s book had a profound influence on Berger and to a great extent, inspired his research.

Ask Berger about it today and he says that 50% of The Tipping Point is wrong— and it is his job to tell you which half. “The Tipping Point is very much based around the idea that certain special people, whether mavens, connectors, or salesmen, are more likely to make things catch on. “There is just no evidence to support that,” he says. “What our research shows is much more focused on the message rather than the messenger. I understand why all sorts of people, whether they have 10 friends or 10,000s, share things and how that drives things to catch on.”

What Berger is talking about is not about the “special people”—Gladwell’s mavens, connectors and salesmen—but the average Joes and Janes. If the message is convincing enough, it will appeal to them as well and encourage them to share. “The size of a forest fire doesn’t depend on the size of the initial spark, it depends on an entire forest being ready to catch blaze. The same is true with social influ¬ence,” explains Berger. Some people may have more friends or followers than oth¬ers, but this doesn’t necessarily translate into greater influence. “By understanding why people share, you can get all sorts of people passing along your message: [again] whether they have 10 friends or 10,000.”

The Science of Viral

Cat memes, Jean-Claude Van Damme’s ‘epic split’ video between two Volvo trucks, Honey Boo Boo clips, specs for the iPhone 6, the twin toilets at the Sochi Olympic stadium. Why do we share what we share? What is the psychology at work here?

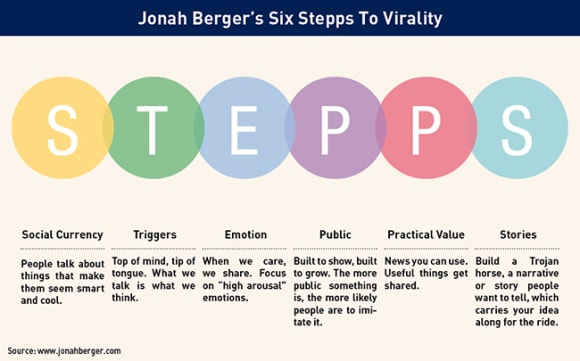

At the end of the day, it all boils down to common sense. Berger’s first principle, Social Currency, for instance, appeals to a very basic need of human beings: the need to look good. “The better something makes us look, the more likely we are to share with others,” he says. “Just like the car we drive and the clothes we wear, what we say affects how other people see us.”

Take the hundreds of people who waited for the new iPhone to be released. “What did they do when they finally got the phone? They took a picture and shared it with all their friends. And if you think about why, the reason is because it makes them look good. Being one of the first peo¬ple to get something that not everyone else has makes you look high status and in-the-know.” Similarly, if we find a funny piece of content, we share it because it makes us look funny—and it makes us look good at finding interesting things on the web.

The second driver—Triggers—means that if something’s top of mind, the more it’s on the tip of a tongue. “If we are think¬ing of something more, it makes us more likely to share it,” says Berger. When Her¬shey’s was trying to rejuvenate Kit Kat, a brand on a downward spiral in 2007, it launched a campaign which positioned the chocolate wafers next to a cup of coffee with the tagline: “A break’s best friend”. Most Americans drink coffee a number of times in one day, and positioning Kit Kat next to coffee created a trigger that would remind people about the brand every time they had coffee. The strategy worked ap¬parently: sales went up by around 8% by the end of 2007, and up by a third at the end of 2008.

The next one is Emotion: if some¬thing activates “high arousal” emotions, we are more likely to share it. “Usually we think about emotion in terms of posi¬tive and negative: you might think that people share positive emotions, because they make other people feel good, and avoid sharing negative emotions because they make others feel bad. But its more complex than that,” says Berger. Emo¬tions differ in how much arousal or activa¬tion they induce. Take anger and sadness. “Neither feels good, but anger is much more action-oriented. People who are an¬gry want to throw something, yell at some¬one, or change something. These high arousal emotions drive people to share,” he adds. “When people feel angry or anx¬ious or when they feel excited, inspired, or laugh, they’re more likely to share. It’s not enough to make people feel good. If you want them to share they need to be excited or inspired.”

The next driver is Public. “Even be¬yond what people are sharing, it’s hard for people to see what they are doing. It’s hard for them to imitate. We often ask others to decide how we behave,” says Berger. “We’ve all heard that phrase ‘monkey see monkey do’. But if we can’t see what each other is doing, it’s really hard to imi¬tate.” He cites the example of portable CD players and the Walkman that were very popular years ago. Then several other new music players came out. They all had black headphones. “But then Apple came out with white headphones [for the iPod],” says Berger. The white headphones and cords stood out among the melee of black headphones. “Suddenly you could see how many other people were using the same device. It helped it to be adopted. It’s easy for people to see what each other is do¬ing and it’s much more likely that they can imitate them, because they can see what’s going on.”

The next driver—Practical Value—is simple. When something is useful, people share it. And the final driver—Stories— people share stories. If you can tie a nar¬rative around your message, the likelihood of it being shared is higher.

A Million Facebook Fans. So What?

Companies are increasingly relying on social media to create a buzz around their brand. Meanwhile consider this: accord¬ing to research by Statista, as of Septem¬ber 2013, retail giant Wal-Mart had 31.1 million Facebook fans in the US (just for perspective, Canada’s population stands at around 35 million). Target came second with 21.1 million and Amazon had 19.1 million. Subway, Starbucks and Oreo also figured on the top 10 list. If you look at Twitter, you’ll find similar mind-numbing figures.

So this is good news for companies, right? Not necessarily.

Companies have embraced social me¬dia with great gusto—they have estab¬lished social media departments, created official Twitter and Facebook pages, and official blogs, gained followers and likes, run social media campaigns, all in the hope that this effort will translate into bet¬ter sales. It may. But what they don’t real¬ize is that they are targeting a small mi¬crocosm of potential customers. “Only 7% of word of mouth is online,” says Berger. “Most is offline or face-to-face.”

So while social media helps create word of mouth, it is only one channel. “Rather than focusing on the technology, it’s more important to think about the psy¬chology—why people share in the first place and why people share some things more than others. That will help compa¬nies design more effective word of mouth marketing campaigns.”

Companies need to also focus on the offline. And how can they do that? “The same rules apply,” says Berger. The basic drivers of why we share remain the same and companies need to understand them first. Companies can design products and retail displays so that people will talk, they can make their service so noteworthy that people have to pass it on.

Do things go contagious offline the same way that they go online? “Things go contagious offline all the time. Think about the last rumor that went around your office or the last news story that ev¬eryone was talking about around the water cooler. People have been sharing all sorts of news and information offline for thou¬sands of years,” says Berger who calls face-to-face conversation the “original” social media.

“The goal is to turn customers into ad¬vocates. You don’t need a viral video, you need each person that interacts with the brand to tell just one more person,” says Berger, who has helped companies like Google, Microsoft, Coca-Cola and Dis¬ney apply the model. “We’ve seen some amazing returns. Everything from 400% increases in Facebook mentions to launch¬ing global brands.”

The writing is on the wall: companies need to reduce their dependence on tradi¬tional advertising. “Word of mouth is 10 times as effective as traditional advertising and it’s cheaper and more likely to gener¬ate sales,” says Berger.

First Published: May 21, 2014, 07:49

Subscribe Now