PayU: On the money

Eighteen months after buying out rival Citrus in India's biggest fintech deal, Naspers-owned PayU turns India into its biggest market globally, and claims to be on the road to cash profits

Shailaz Nag, MD, and Amrish Rau (right), CEO, have made PayU a leaner machine by exiting the wallets and PoS businesses Image: Madhu Kapparath

Shailaz Nag, MD, and Amrish Rau (right), CEO, have made PayU a leaner machine by exiting the wallets and PoS businesses Image: Madhu Kapparath

Shailaz Nag code named the operation ‘Yes, we can’. The goal set by the gritty entrepreneur in February last year was as arduous as the one fixed by the then president-elect of America Barack Obama in November 2008. ‘Yes, we can’, thundered the first black president of the US from his home city of Chicago as he tried to rekindle hopes of reclaiming the American dream.

Back in Gurugram, Nag, the co-founder of payment gateway company PayU, too, was at his inspirational best. “Yes we can,” he yelled, as over 900 employees broke into thunderous applause, motivated by the hope of turning the tide.

PayU, owned by South African media and ecommerce biggie Naspers, was stacked against heavy odds: Losses had mounted to ₹249 crore in 2016-17 revenue increased to ₹429 crore, though at a laboured pace and the company was in real danger of missing the post-demonetisation bus by trying to do too many things.Just five months after buying out rival Citrus Pay in an all-cash deal of $130 million—India’s biggest fintech transaction—in September 2016, Naspers’s dream of making it big with PayU was nowhere close to realisation. “We have to make it work, make it right and make it fast,” Nag addressed the overflowing auditorium, as it reverberated with ‘Yes, we can’ chants.

Cut to June 2018. India has become the biggest market for PayU. And it’s profitable.

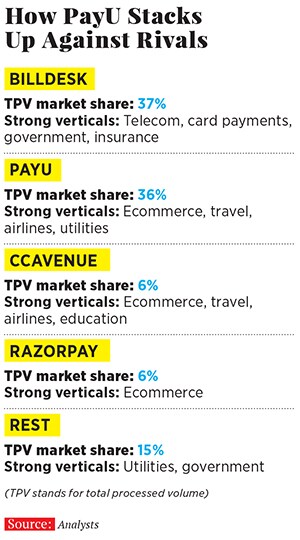

For the March 2018-ended fiscal, the payments and fintech business of Naspers—which operates in 17 countries—recorded revenue growth of 58 percent. The icing on the cake though is India’s performance: While the total payment value of PayU exceeded $25 billion, India accounted for 47 percent.

“India is today a big part of our global fintech story and our profitability will allow us to grow more,” contends Laurent Le Moal, chief executive officer at PayU Global. India is also the fastest-growing region for PayU, with an 84 percent jump in payments volume.

The profits, though, came only in March, but the good news is that the Indian operations maintained that trend for three consecutive months.

‘YES, WE CAN’

Nag recounts how the team would religiously chant ‘Yes we can’ every morning at 10.30. This went on for over six months. From 10.30 am to noon every day, the leadership team brainstormed. The next day, for the first 20 minutes, the previous day’s performance would be reviewed. “The six months, from February to July were phenomenal,” he says, adding that the employees celebrated the first anniversary of the project in February this year.

From red to black wasn’t a walk in the park. The biggest stumbling block resulted from the buyout itself: The work overlap that came with it. Though both the companies stopped competing against each other, the new issue was lack of focus. “We were all over the place, trying to do too many things,” avers Nag. The merged entity was draining its energy and resources in four businesses: Enterprise, PoS (point of sale), small and medium businesses (SMB) and wallet.

Although the core of the merged entity lay in online payments, it took a while for PayU to discover the reality. Demonetisation did its bit in delaying the self-realisation as daily transaction volumes skyrocketed by 80 percent after November 8. However, simultaneously, PayU was burning cash and losing money hand over fist. The wallets business—PayU and Citrus had their own wallets—was proving a drag.Nag and B Amrish Rau, former managing director of Citrus, decided to get rid of the wallet albatross. “UPI [the National Payments Corporation of India’s Unified Payments Interface] has killed the wallet. We were fortunate to realise a few years back that wallets didn’t have a future,” reckons Rau, now chief executive officer of PayU.Another move to plug the leaking bucket was to take a hard look at the PoS business, rolled out in June 2016.

The logic to enter the business was simple: India had about 1.2 million PoS machines and about 0.7 million small and medium merchants had access to them. To put it another way, there were only 693 PoS machines per one million users in India as against 4,000 and 32,995 in Russia and Brazil, respectively. This, according to a 2015 Ernst & Young report.China was another inspiration to take the plunge. From 15.93 million PoS machines in 2014, China grew to 22.82 million machines by end of 2015. PayU expected a similar growth trajectory. Though demonetisation did give a big push to PoS, PayU had made up its mind to have a focussed approach. Last May, PayU exited the offline business.

The job, though, was still half done. After restructuring the business units, the focus shifted to maximising operational efficiencies. A heavy headcount—1,200 after the buyout of Citrus—coupled with proliferation of multiple teams without any synergies was doing little good. Rau had to bite the bullet. Headcount was slashed by over 40 percent. “At 1,200, we could have lost our efficiencies. Fintech companies must not be [people] heavy,” avers Rau, who took another bold step to control costs.

“We completely stopped buying loss-making transactions. Today not a single transaction that we process is loss making,” he claims.

Rau’s claim matches the financial numbers. Cash burn for the March-ended fiscal stood at ₹8 crore, a fall from ₹24 crore in 2016-17. The loss for fiscal year 2018 dropped to ₹98 crore from ₹249 crore a year earlier. By fiscal year 2019, PayU hopes to wipe out its losses.

Although PayU has posted three months of continuous profit since March, Rau has a different take on bottom line. “Losses don’t scare me,” he says. If our losses are too low, he argues, it means that a company is too conservative. But if losses are too high, you are becoming too much of a salesman. “We don’t want to make this a hugely profitable business,” he contends, adding that the worrying thing about losses is the bad habit that come along with them: That of buying business.

Making a timely exit from wallets, reckon analysts, brought back focus to PayU.

Post-demonetisation, wallet companies went ballistic, spending insane amounts of money on advertising and marketing. “They were burning [the candle] from both ends,” says Anil Joshi, founder at Unicorn India Ventures, a Mumbai-headquartered early stage venture capital fund. Though a bit of the burn was required initially, it clearly could not be sustained over the longer run. “PayU realised the non-viability of the wallet,” adds Joshi. By restricting cash burn on the wallet, it could focus on more profitable solutions, he adds.

The Citrus buyout helped boost the top line—from ₹429 crore in 2016-17 to ₹653 crore in 2017-18, taking PayU towards becoming a $100 million company. And there were other benefits of the acquisition. “In many ways, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that PayU has turned profitable,” says Shubhankar Bhattacharya, Venture Partner at Kae Capital. “After all, the Citrus acquisition implied that it didn’t have to deal with competitive pressures,” he adds. Bhattacharya, however, is quick to point out that one should not trivialise PayU’s success given that not all fintech mergers in India have worked out as well.

A case in point is the acquisition of Freecharge by Snapdeal and later by Axis Bank. According to the latest Registrar of Companies (RoC) filings data reported in the media, the wallet player reportedly recorded an 11.5X jump in losses to ₹356 crore in fiscal year 2017 from ₹30.9 crore in the preceding fiscal. “Kudos to Naspers. PayU’s profitability adds to their already impressive track record of investing and building businesses in India,” says Bhattacharya.

NASPERS’ GLOBAL PUSH

What might have also nudged PayU India to tread the profit path was the global vision of Naspers in turning PayU profitable globally. “Profitability is an objective that we have for the whole company and not just for India,” says Moal of PayU Global. India is the first country to turn profitable for PayU. Now, some Latin American nations too have posted profits. From a newspaper publisher founded more than 100 years ago in Stellenbosch in South Africa, Naspers has transformed itself into Africa’s most valued company with a valuation of $104 billion with operations in 120 countries—primarily classifieds, food delivery and fintech. The hefty valuation is courtesy a 31 percent stake in China’s biggest internet firm Tencent, which is worth $149 billion, or roughly 40 percent more than Naspers. Early this year in March, Naspers raised $9.8 billion from the sale of a 2 percent stake in Tencent. That helped boost fiscal year 2018 earnings to $11.36 billion, up from $2.34 billion a year ago. “This gives us the firepower to invest in key areas such as online classifieds, food delivery and fintech, and to move into new areas like edtech,” Basil Sgourdos, group chief financial officer, told American news weekly Barron’s last fortnight.

From a newspaper publisher founded more than 100 years ago in Stellenbosch in South Africa, Naspers has transformed itself into Africa’s most valued company with a valuation of $104 billion with operations in 120 countries—primarily classifieds, food delivery and fintech. The hefty valuation is courtesy a 31 percent stake in China’s biggest internet firm Tencent, which is worth $149 billion, or roughly 40 percent more than Naspers. Early this year in March, Naspers raised $9.8 billion from the sale of a 2 percent stake in Tencent. That helped boost fiscal year 2018 earnings to $11.36 billion, up from $2.34 billion a year ago. “This gives us the firepower to invest in key areas such as online classifieds, food delivery and fintech, and to move into new areas like edtech,” Basil Sgourdos, group chief financial officer, told American news weekly Barron’s last fortnight.

In May this year, Naspers sold its 11.18 percent stake in Flipkart to Walmart for $2.2 billion. The South African ecommerce and media giant had bought into Flipkart in 2012 and invested a cumulative $616 million.

“India is one of the most exciting markets in the world. We are proud to back Indian entrepreneurs whom we believe have what it takes to build outstanding and long-lasting businesses, and Flipkart is a great example of this… we are excited about the future of OLX, PayU, Swiggy and MakeMyTrip,” Bob van Dijk, Group CEO of Naspers, reportedly said after the stake sale in Flipkart.  DIGITAL PAYMENTS SKYROCKET

DIGITAL PAYMENTS SKYROCKET

What has whet the appetite of the South African conglomerate, along with the Chinese brigade led by Alibaba, is the unprecedented business opportunity that India presents. Digital payments are expected to hit the $500-billion mark by 2020, according to a report by Boston Consulting Group. The number of smartphone and internet users, the 2016 study predicts, will double to 520 million and 650 million, respectively, by 2020. “India truly seems to be going digital,” the study concludes.

Digital transactions in India, predicts ACI Worldwide and AGS Transact Technologies in its report in March this year, could be worth $1 trillion annually by 2025, with four out of every five transactions being made digitally.

Clearly, PayU has just scratched the surface, and Naspers is aware of the massive opportunity. “India is the most exciting place for the payments ecosystem,” says Le Moal of PayU Global.

Naspers is now eyeing services beyond payments. “The country offers an even bigger opportunity in the form of access to credit and other financial services,” says Le Moal, explaining how India has an untapped opportunity in credit as it had over 37 million credit cards and 861 million debit cards as of March 2018. The numbers are growing. Between March 2017 and March 2018, India added some 7.68 million credit cards and 6.18 million debit cards, according to Reserve Bank of India data.

While the number of transactions using credit cards grew by 20 percent year-on-year, it increased by 17.6 percent for debit cards for the 12-months ended March 2018. Naspers, Le Moal asserts, is now betting big on credit as the next phase of growth. “Our credit business is one of our big bets this year.”  CREDIT: THE NEXT GROWTH ENGINE

CREDIT: THE NEXT GROWTH ENGINE

Back in India, Rau is getting ready for the next phase of growth. “We have won the merchant battle, now it’s time to open a new front on the consumer side,” he says, contending that data would be the new ammunition to wage a credit war.

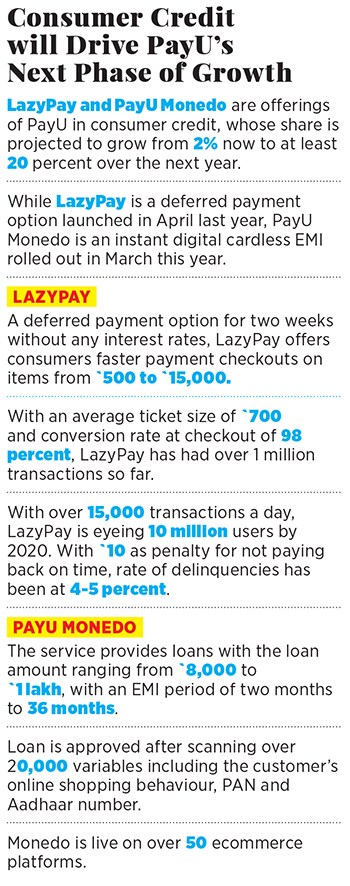

Over 78 million unique cards have transacted on PayU, 30 million unique cards have been stored, 1 million new stored cards are added every month, 5 billion unique data points on consumers are available, 2.5 transactions online are done by an average consumer every month and 70 percent of transactions are now on mobile. Consumer behaviour patterns, Rau claims, for practically all online shoppers in India are with PayU. “This huge data will help us drive our credit business, which now accounts for just 2 percent of revenue,” he adds.

LazyPay and PayU Monedo are the twin engines that will drive the credit business. A deferred payment option for two weeks without any interest rates, LazyPay offers consumers faster payment checkouts on items from ₹500 to ₹15,000. With an average ticket size of ₹700 and conversion rate at checkout at 98 percent, LazyPay has had over 1 million transactions so far. “With over 15,000 transactions per day, LazyPay is eyeing 10 million users by 2020,” says Rau. With LazyPay taking off, a similar ambitious push is planned for Monedo.

Launched in March, Monedo offers loans ranging from ₹8,000 to ₹1 lakh for online purchases, with an EMI period of 2 to 36 months. The product was launched in partnership with German fintech company Kreditech, which provides its machine learning-based real-time underwriting capabilities. Loans are approved after scanning over 20,000 variables, including online shopping behaviour, PAN and Aadhaar details.

CHALLENGES GALORE

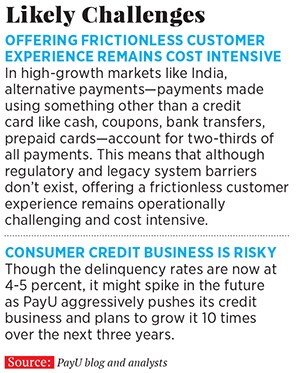

Notwithstanding the aggressive intent of Rau to scale up the credit business at least 10 times over the next three years, the going might not be easy. Reason: Credit is a double-edged sword. Though it presents a massive opportunity, the flip side of consumer defaults on payments could be potentially devastating. Even though the credit business for PayU now is just 2 percent of its revenue, the default rate is 4-5 percent. Bhattacharya of Kae Capital makes a pertinent point: While PayU enjoys certain unfair advantages due to its market leadership in the payments space, it is hard to say how well that will translate into success on the credit side.

Bhattacharya of Kae Capital makes a pertinent point: While PayU enjoys certain unfair advantages due to its market leadership in the payments space, it is hard to say how well that will translate into success on the credit side.

While conceding that credit and consumer-centric financial services represent a massive opportunity, Bhattacharya maintains that it is also a competitive and cluttered market. There are multiple players in the fintech ecosystem—banks and other financial services providers, mature and well-funded startups as well as upstarts and foreign market entrants—all vying for a share of the Indian consumer credit market.

Though PayU might not immediately appear to be under threat from UPI-enabled payment solutions like WhatsApp, Tez and PhonePe, the China story (where WeChat Pay and AliPay have become the dominant payment solutions) suggests that there might eventually be a showdown between all these players for a winner-takes-all scenario.

Another challenge could be offering a frictionless customer experience, which is likely to remain cost intensive. In high-growth markets like India, PayU acknowledges in one of its blog posts, alternative payments—payments made using something other than a credit card, like cash, coupons, bank transfers, prepaid cards—still account for two-thirds of all payments. “This means that although regulatory and legacy system barriers don’t exist, offering a frictionless customer experience remains operationally challenging and cost intensive,” the blog concludes.

PayU will also be aware of its history of making a well-planned entry into new territories like PoS but exiting after not tasting success.Rau, for his part, sounds confident. One needs to understand, he reckons, that there will be losses, there will be things that one doesn’t feel comfortable about. “But one has to manage things,” he says, stressing that another lever for growth will come from collaborating with the global team in enabling companies enter India.

Earlier this year, PayU announced its partnership with Zara to launch its online retail stores in India. Zara, which works with PayU globally, was keen to launch its online retail stores in India. PayU Global Sales, in cooperation with the India team, managed to provide Zara’s parent company Inditex insight into the local ecommerce payment landscape, informs Rau, adding that PayU has also applied for an NBFC licence to speed up its business.

“If PayU does not create a company which is $5 billion in the next 3-4 years, we would have missed an opportunity,” he says. Ask him if the target is achievable, pat comes the reply: “Yes, we can.”

First Published: Jul 05, 2018, 11:44

Subscribe Now