How can Union Budget 2020 be made gender sensitive?

The government will have to be more innovative, inclusive and responsible with fiscal allocations for women

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur[br] In her 2019 Union Budget speech, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman waxed eloquent about naari being a narayani (women being goddesses). She said a “bird cannot fly on one wing” while stressing on the equality of men and women in India’s development story. Sitharaman even proposed forming a broad-based committee with “government and private stakeholders” to evaluate the budget with a gender lens and pave the way for more inclusive fiscal outlays. One year on, the committee remains only on paper, while development indices for Indian women have never been more bleak.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur[br] In her 2019 Union Budget speech, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman waxed eloquent about naari being a narayani (women being goddesses). She said a “bird cannot fly on one wing” while stressing on the equality of men and women in India’s development story. Sitharaman even proposed forming a broad-based committee with “government and private stakeholders” to evaluate the budget with a gender lens and pave the way for more inclusive fiscal outlays. One year on, the committee remains only on paper, while development indices for Indian women have never been more bleak.

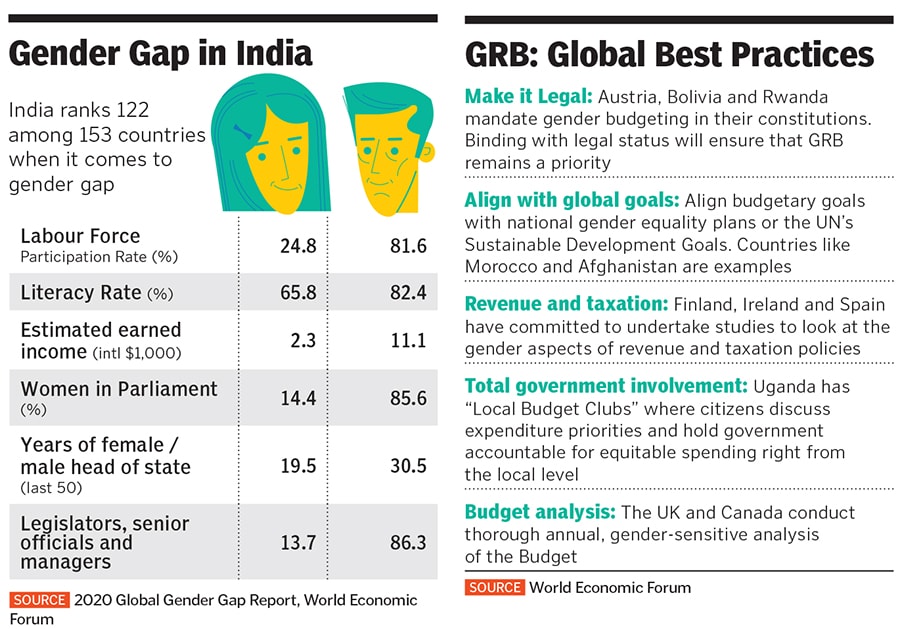

The Global Gender Gap Report 2020 released by the World Economic Forum (WEF), for instance, indicates that India slipped four ranks from last year to 112 among 153 countries. The report measures how countries perform in reducing women’s disadvantage compared to men in politics, economic empowerment, health and education. India’s overall ranking is 14 positions lower than where it was in 2006, when the WEF first started measuring gender gap.

The economic disparity between men and women in India is particularly staggering, according to the report, with only one-third (35.4 percent) of the distance being bridged. India ranks among the bottom four countries of the world when it comes to economic participation and opportunities for women (rank 149), followed by health and survival (rank 150).

At the same time, estimated budget outlays for the ministry of women and child development (WCD) have only increased consistently in the last three years. In 2017, the total budget estimate for the WCD was ₹22,095 crore, nearly a 20 percent increase from ₹17,640 crore the year before. In 2018, this allocation was hiked by almost 12 percent to ₹24,700 crore. Last year, Sitharaman increased the outlay by another 17 percent to ₹29,000 crore. Many women-oriented schemes received heavy backing during the same time, including homes and shelters for widows, the government’s flagship ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’, Mahila Shakti Kendras, and the maternity benefit programme Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana.

Economists and policy experts believe that budgetary allocations have not translated into on-ground development largely because of the lack of targeted expenditure backed by adequate research and analysis. Other factors include low implementation at the state and district-levels, less emphasis on data collection and interpretation, incomplete inclusion of the informal sector into the process, and limited to no accountability among government officials. Outlay vs Outcomes

Outlay vs Outcomes

As an essential first step to gender budgeting, inputs need to drive the right outcomes, and the outcomes have to be connected to human development indices (HDIs). Lekha Chakraborty, professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), calls the lack of macro-framework for gender the “biggest lacuna” in the budgeting process.

“Gender development is highly fragmented at the micro and sectoral levels. If we can identify, say, five gender development goals for the medium term, set targets to be reached, along with the processes, the path and the budgetary backup, it will be easy to follow that roadmap. The ministry of finance (MoF) can take the lead in making this ‘roadmap’ happen,” she says. The team at NIPFP pioneered the research related to the introduction of gender budgeting in India back in the early 2000s, besides getting it institutionalised within the MoF.

Gender-responsive budgeting (GRB) was introduced in 2004 as a “silent revolution”, says Chakraborty. The idea was not to produce a separate budget for women, but to apply a gender lens to fiscal expenditure and allocate funds with a priority on gender-specific outcomes. That the policymakers took essential steps to institutionalise GRB at the MoF level is often seen as a strength.India has been producing gender-budgeting statements as part of the Union Budget since 2004-05. It is divided into two parts, depending on the intensity of the gender component in public expenditure. Part A includes schemes that are 100 percent targeted for women, while Part B is composite schemes with at least 30 percent benefits to women.

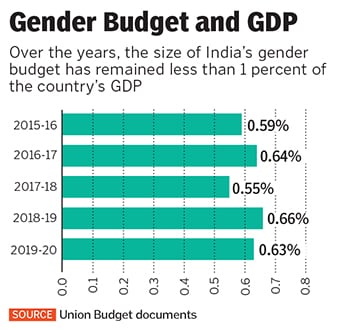

In 2015, the WCD ministry also released a handbook on gender budgeting, offering states comprehensive implementation guidelines. Yet, as of today, only about 16 states have undertaken GRB, while the gender budget occupies less than 1 percent of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The spending on gender has not increased proportionately with the Union Budget either, with the GRB as a percentage of total expenditure hovering mostly between 3 percent and 6 percent in the last decade.

“GRB in India is still more about aggregation of allocations and expenditures for women-centric schemes. There is no real focus nor is it used enough as a policy tool for a more gendered discourse of implications,” says Avani Kapur, fellow, Centre for Policy Research. She believes gender weights are assigned to expenditures with a degree of arbitrariness. “That the entire Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana [affordable housing scheme] allocation is being reported as 100 percent women [in Part A of the Budget] is a case in point.”

Chakraborty says that even within allocations, the gender budget shows signs of fiscal marksmanship, which refers to the deviation between budgetary promises and reality. “Just announcing a flagship programme in the Budget also needs to be taken with caution,” she says, explaining that higher budgetary allocations do not guarantee higher spending on women.

For example, an analysis of the gender budget indicates that the budgetary allocation of ₹267 crore for the National Mission for Empowerment of Women in 2018-19 was revised to ₹115 crore. Similarly, allocations under the Ujjawala (distribution of LPG connections) scheme was slashed from ₹60 crore to ₹20 crore during the same period. Chances are that the actual on-ground spending might be even lower than the revised estimates. “We need independent institutions like fiscal councils to capture fiscal marksmanship. They act as watchdogs,” says Chakraborty, confirming that the broad-based committee for gender budgeting, as announced by the finance minister, has not been constituted yet. Officials from the WCD ministry, under whom this committee is to be formed, did not respond to Forbes India’s queries.

Experts point out that spending on gender is usually concentrated with four or five ministries, and that the Budget in February is an opportunity to diversify allocations. For example, as per Union Budget documents, between 2016 and 2019, about 35-37 percent of the gender budget was allocated to the ministry of rural development, followed by about 19 percent for health and welfare, 19-22 percent for human resource development and 12 percent to the WCD ministry. In short, about 85 percent of the total gender budget allocation was just within these four ministries.[br]“There is no planning on how to make this expenditure more effective for women,” says independent economist Mitali Nikore. “The MSME department, for example, runs about 300 government schemes. Why doesn’t any of it have a gender lens? Textile and food processing industries employ maximum women workers, then why aren’t allocations done keeping that in mind? The gender budget needs to focus on specific industries and departments.”

A large part of the problem might also be a mindset that views women as maternal or reproductive entities and not economic drivers, adds Tara Krishnaswamy, co-convenor, Shakti, a non-partisan collective working to increase women’s participation in legislature. She might not be far off the mark. Last year, the Centre’s allocations for mother and child welfare got a major boost. The maternity benefit outlay under the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana was doubled from ₹1,200 crore to ₹2,500 crore, while the budget for the Integrated Child Development Services increased from ₹925 crore to ₹1,500 crore.

“While it is supremely important to have healthy mothers and children, we need to help women be productive contributors to the economy,” Krishnaswamy explains. “Focus on revenue and tax benefits for working women. For example, women are much more part-time workers than men are, and in countries like the US, you have health insurance benefits for part-time work, which act as an incentive for keeping women in the workforce.” The Budget, she adds, must also be more inclusive of women in unpaid care or informal economy. From Paper to Practice

From Paper to Practice

An April 2018 report by the McKinsey Global Institute says India could add more than 18 percent (up to $770 billion) to its GDP simply by giving equal opportunities to women. Legislators and party representatives suggest this might also be key to India’s goal of becoming a $5 trillion economy. “The government must increase fair participation of all three genders in budget preparation. Often, it is more men in the bureaucracy who work on the budget.” says Apsara Reddy, national general secretary, All India Mahila Congress, who believes that gender narratives must be mainstreamed into public finance management on priority.

Implementation of gender budgets at the district and state level is a half-baked story, given the lack of capacity, shortage of funds and absence of accountability mechanisms. For example, Kerala—one of the early-adopters of the gender budget along with Odisha, Karnataka, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar—faces problems ranging from lack of gender disaggregated data to no dedicated gender budget cells.

“We have not been able to evaluate the impact of gender allocations so far for various reasons, ranging from lack of funds to low gender rights awareness among people. We’ll pursue it aggressively after the upcoming Budget,” says Dr Mridul Eapen, member, Kerala State Planning Board. The impact assessment will involve, she says, evaluating women’s welfare institutes, making schemes like the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) more female-friendly by ensuring equal wages, sanitation and child care facilities for women, increasing security and workforce participation. “For example, Kerala’s Startup Mission was supposed to put aside 10 percent of the ₹70 crore they received for women-led startups. We will follow up if they have done that,” she says.

According to Eapen, most states find it difficult to pursue gender budgeting effectively because of a disconnect between the finance, women and child development, and other departments. “In Kerala, the Planning Board acts as a nodal agency that ensures gender-related policies exist across sectors. It is important that individual departments integrate gender components in the planning process itself, rather than an afterthought.”

Economist Nikore says the government should not centralise provisions. “Decentralised expenditure will lead to inclusive spending. Central schemes like ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ must be more participative, with state governments having more autonomy in implementing them.”

It is also important for the government to conduct and publish surveys offering insights on gender development periodically, says Krishnaswamy. “The current government, from 2014 to date, has dialled down on surveys. So it is becoming impossible to know, even at the state level, what the accurate numbers are in order to measure the impact of programmes,” she says. “And where we have data, it is not collected and interpreted properly. The whole notion of data-driven governance with a systematic, scientific mindset has not caught up in India at all.”

In order to get out of this vicious circle of low socioeconomic opportunities leading to less budgetary allocations for women, it is important to politicise and talk about gender, Krishnaswamy believes. “Right now, the gender budget feels like a checkbox that the government is not even serious about. There is a complete dearth of imagination and innovation as far as fiscal policies are concerned. You cannot magically reach the $5 trillion economy mark without empowering your women first.”

First Published: Jan 22, 2020, 09:59

Subscribe Now